For decades, the story of mental illness has been told in many threads, woven from environmental influences, life experiences, and a wide web of genetic factors. Scientists believed no single source could explain disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, or anxiety. Instead, many small influences seemed to act together, overlapping in ways too complex to untangle. But a new international study led by the Institute of Human Genetics at the University of Leipzig Medical Center has cracked open that long-held belief, revealing a surprising new chapter in the biology of the mind.

The researchers did not set out to overturn this narrative entirely; they simply followed the data. Yet what they found forced them to look again at something everyone assumed they already understood. This time, instead of many genes whispering small influences, one gene stood alone speaking loudly enough to change everything.

A Gene Steps Out of the Shadows

That gene is GRIN2A, a tiny fragment of DNA with an outsized impact on how nerve cells communicate. It was not unknown to science—far from it. GRIN2A had long been linked to neurological conditions such as epilepsy or intellectual disability. What no one expected was what the new data revealed when 121 individuals carrying a genetic alteration in GRIN2A were studied together.

“Our current findings indicate that GRIN2A is the first known gene that, on its own, can cause a mental illness. This distinguishes it from the polygenic causes of such disorders that have been assumed to date,” says Professor Johannes Lemke, lead author of the study and Director of the Institute of Human Genetics at the University of Leipzig Medical Center.

This sentence lands like a stone dropped into still water. It suggests something astonishing: that in at least some cases, a single change in a single gene can be enough to set a person on a path toward psychiatric illness. No interplay of dozens or hundreds of tiny genetic nudges. No complex tapestry. Just one gene acting alone.

And the surprises did not end there.

Childhood Clues in an Adult Puzzle

Mental illnesses such as schizophrenia typically surface in adulthood. But the study revealed that when GRIN2A is altered, the story often begins much earlier.

“We were able to show that certain variants of this gene are associated not only with schizophrenia but also with other mental illnesses. What is striking is that, in the context of a GRIN2A alteration, these disorders already appear in childhood or adolescence—in contrast to the more typical manifestation in adulthood,” says Professor Lemke.

For clinicians, this timing is not a minor detail. Childhood symptoms suggest a biological disruption that is baked into development, appearing long before life’s challenges could shape a person’s mental state. It shifts the question from What happened to this child? to What is happening inside their cells?

And in a twist that further deepened the mystery, some of the affected individuals showed nothing but psychiatric symptoms—no epilepsy, no intellectual disability, no other neurological signs. GRIN2A was doing something much more specific than expected.

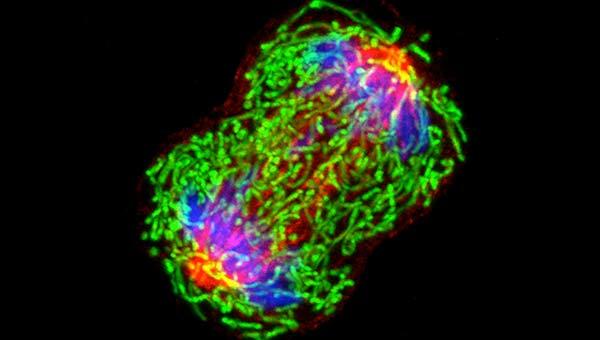

Inside the Electrical Language of the Brain

To understand how a single gene could cause such profound effects, the researchers looked closely at what GRIN2A actually does. It plays a central role in regulating the electrical excitability of nerve cells, a delicate process essential for thought, emotion, perception—everything that makes consciousness function.

The study found that certain GRIN2A variants led to reduced activity of the NMDA receptor, a key molecule involved in transmitting signals between brain cells. When the NMDA receptor falters, so does the brain’s ability to communicate smoothly with itself. The electrical harmony becomes disrupted, and with that disruption, the symptoms of mental illness begin to emerge.

This discovery did more than explain the problem. It opened a door to something even more unexpected: the possibility of treatment.

A Glimmer of Hope Through an Unlikely Source

Together with Dr. Steffen Syrbe, Professor at the Heidelberg Medical Faculty and pediatric neurologist at Heidelberg University Hospital, the research team explored whether these molecular changes could be influenced therapeutically. The idea was simple but bold: if reduced NMDA receptor activity contributes to symptoms, could boosting that activity offer relief?

In an initial treatment series, they found a striking result. Patients showed marked improvements in their psychiatric symptoms after receiving L-serine, a dietary supplement known to activate the NMDA receptor.

It was only a first step, not a final answer. But in the landscape of mental health—where progress often comes slowly and uncertainty is familiar—the improvement was notable enough to spark hope.

The collaboration between Professors Lemke and Syrbe has spanned nearly fifteen years. Their shared focus on disorders of the glutamate receptor in children laid the groundwork for this discovery. Over time, Lemke also built an international registry of GRIN2A patients, now the largest in the world. This global effort provided the foundation for the current study, allowing patterns that once seemed scattered and isolated to finally come together.

Why This Research Matters

This research does not erase the complexity of mental illness. It does not claim that all psychiatric disorders emerge from a single cause. But it does something equally important: it proves that in at least one case, a single gene can indeed be responsible—fully, directly, and independently—for a mental illness.

That knowledge changes the landscape. It challenges long-held assumptions about genetics and mental health. It opens the possibility of earlier diagnosis for children whose symptoms might otherwise be misunderstood or overlooked. And it hints at future treatments that address the underlying biology rather than only the symptoms.

In a world where nearly one in seven people live with a mental illness, according to the World Health Organization, the importance of understanding these origins cannot be overstated. Each insight lifts a shadow, offering clarity where once there was only uncertainty. The discovery of GRIN2A’s singular role does not answer every question, but it illuminates a path—one that leads toward deeper understanding, more precise care, and a future where mental illness can be addressed not only with compassion but with biological precision.

In the story of the human mind, this is not the final chapter. But it is a groundbreaking one.

More information: Johannes R. Lemke et al, GRIN2A null variants confer a high risk for early-onset schizophrenia and other mental disorders and potentially enable precision therapy, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03279-4