For most of history, sharks have left behind only whispers of their existence. A tooth here. A jagged edge there. Sharp, mineralized fragments scattered through stone. Their bodies, built mostly from cartilage, vanish almost as quickly as they fall to the seafloor. Unlike bone, cartilage rarely survives the long journey into deep time.

But in northwestern Arkansas, something extraordinary happened more than 300 million years ago.

Beneath ancient waters, in what is now known as the Fayetteville Shale, dozens of sharks escaped the usual fate of dissolution and decay. Their skeletons—three-dimensional and remarkably intact—were sealed into stone. Not flattened impressions. Not scattered fragments. Entire forms, preserved in astonishing detail.

In a new study published in Geobios, researchers have uncovered the secret behind this unlikely survival. The answer lies not in the sharks themselves, but in the strange chemistry of the seafloor where they came to rest.

Why Sharks Usually Disappear

To understand why these fossils are so extraordinary, it helps to understand how fragile shark skeletons really are.

Sharks are not built like most fish. Their internal framework is made of cartilage, the same flexible tissue found in our ears and noses. Cartilage is lightweight and resilient in life, but in death it is vulnerable. It breaks down quickly. Bacteria feast on it. Chemical reactions dissolve it. Before it can turn to stone, it is usually gone.

That is why the fossil record of sharks is dominated by teeth. Teeth are hard and mineralized, perfectly suited for fossilization. Skeletons are another story entirely.

“The fossils provide a glimpse into shark anatomy unparalleled for this period of time anywhere in the world,” says lead author Allison Bronson, a Biological Sciences professor at Cal Poly Humboldt.

For the era these fossils come from—around 326 million years ago—such preservation is almost unheard of. Cartilage is so rare in the fossil record that any site preserving it becomes instantly invaluable.

The Fayetteville Shale is not just rare. It is transformative.

Rebuilding an Ancient Ocean Floor

To uncover why these sharks survived when so many others did not, Bronson and her colleagues set out to reconstruct the world they inhabited.

Working with researchers from the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, the University of Lausanne, and Carleton University, the team examined the fossils and the surrounding rock with a powerful set of tools. They used X-ray diffraction, X-ray fluorescence, and high-resolution CT scans to peer inside both the stone and the skeletons it cradled.

The fossils themselves are part of the AMNH’s Mapes Collection, donated in 2013 by co-author Royal Mapes, who contributed not only these rare shark skeletons but approximately 540,000 additional fossils. The collection is vast, and it continues to reveal new insights.

By analyzing the chemistry locked inside the shale, the researchers reconstructed the conditions of the ancient seafloor. What they found was not an inviting environment. It was hostile, extreme, and strangely protective.

The seafloor where these sharks settled was marked by low oxygen levels and high acidity. At first glance, that sounds destructive. Acid dissolves. Oxygen fuels decay. Yet in this case, those conditions changed the rules.

The low-oxygen environment slowed the activity of decay-causing bacteria. With less oxygen available, microbial breakdown happened more slowly. At the same time, the high acidity degraded materials like bone and shell more readily than cartilage.

It was a paradoxical balance. The environment suppressed bacterial decay, giving cartilage a chance to persist, while chemically eroding harder skeletal materials. The result was a fossil record rich in sharks and strangely poor in other fish.

Even though bony fish were widespread globally at the time, the Fayetteville Shale contains very few of them. Their bones and shells did not fare well under those acidic conditions. Sharks, built differently, endured.

The Birth of “Sharkansas”

The scientists have given this extraordinary fossil site a nickname: “Sharkansas.”

It is not just a clever play on words. It reflects the remarkable concentration of well-preserved shark fossils found there. According to Bronson, this formation represents one of the most important sites in the world for studying shark evolution during the Paleozoic.

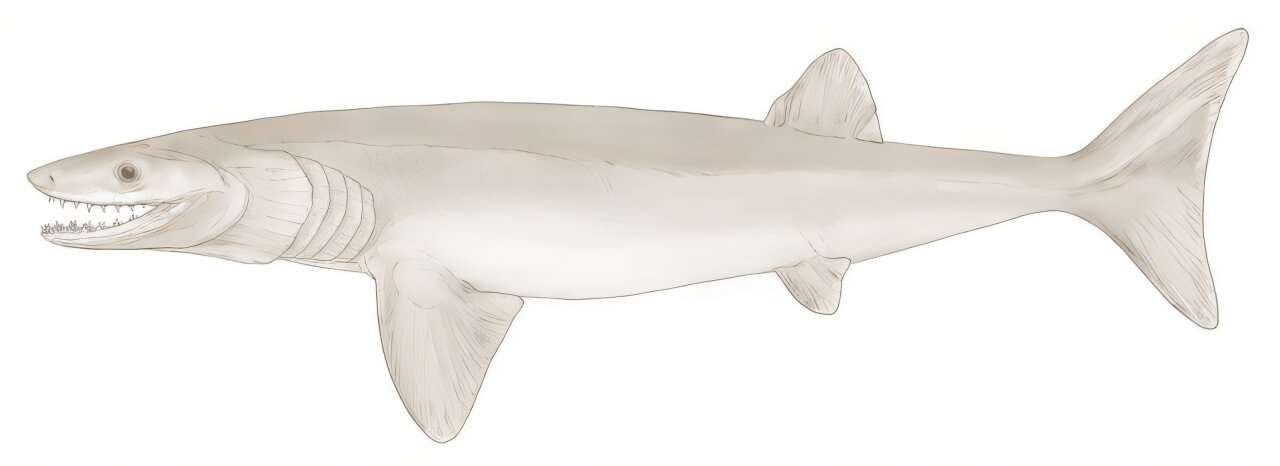

Among the preserved species are Ozarcus mapesae, Cosmoselachus mehlingi, and Carcharopsis wortheni. These ancient sharks have helped improve our understanding of fish evolution, offering anatomical details that would otherwise have been lost.

What makes “Sharkansas” truly special is not simply the number of fossils, but their condition. These skeletons were preserved in three dimensions. In most fossil sites, if cartilage is preserved at all, it is flattened by the immense pressure of overlying sediments. Shapes are distorted. Structures collapse. Fine details vanish.

Here, the fossils retain depth and volume. Researchers can visualize delicate structures such as the cranium, inner ear, and even the brain cavity. These are parts of the anatomy that are often crushed beyond recognition in other fossil deposits.

Imagine holding a fossil that still reveals the shape of a shark’s head, the contours of its sensory organs, the cavity that once housed its brain. It is as close as science can come to looking back in time without a time machine.

A Chemical Signature With Global Implications

The discovery goes beyond explaining one remarkable fossil site. By identifying the precise chemical and sedimentary conditions that allowed cartilage to fossilize, the study offers a roadmap for paleontologists searching elsewhere.

If similar combinations of low oxygen and high acidity can be found in other ancient rock formations, those sites may also harbor rare cartilage fossils. The Fayetteville Shale becomes not just a treasure trove, but a guide.

Bronson and her colleagues plan to revisit “Sharkansas” in the future. But even without returning to the field, there is still much to uncover. The AMNH collections remain rich with material waiting to be studied.

“Each time I visit the museum’s Fossil Fish collection, I discover something new,” Bronson says.

That sense of discovery—the idea that answers are already sitting in drawers, waiting for the right questions—adds another layer to the story. The fossils have been preserved for hundreds of millions of years. We are only just beginning to understand them.

Why This Discovery Matters

The Fayetteville Shale challenges what we thought we knew about fossil preservation. For decades, the absence of cartilage in the fossil record has limited our understanding of early sharks. Scientists have often had to reconstruct entire animals from teeth alone, filling in the rest with cautious inference.

Now, thanks to the unusual chemistry of an ancient Arkansas seafloor, we have something far more complete.

These fossils provide direct evidence of shark anatomy from a time more than 326 million years ago. They allow researchers to examine structures that are critical for understanding how early sharks lived, sensed their environment, and evolved. They help clarify the broader story of fish evolution during the Paleozoic era.

Equally important, the study reveals that fossil preservation is not random. It is governed by chemistry, environment, and timing. By decoding those factors, scientists can better predict where other rare fossils might be hidden.

In a world where most ancient sharks are reduced to scattered teeth, “Sharkansas” stands as a reminder that sometimes, the past survives against the odds. In the silence of a low-oxygen, acidic seafloor, cartilage endured. Bacteria slowed. Chemistry shifted. Stone formed.

And because of that improbable chain of events, we can now look deeper into the history of sharks than ever before.

Study Details

Allison Bronson et al, Vertebrate assemblage and depositional environment of the Fayetteville Shale (Upper Mississippian, middle Chesterian), Geobios (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.geobios.2025.11.002