Far below the surface, where light never travels and the sediment grows by only a thousandth of a millimeter each year, a forgotten world has been waiting. For decades, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone—an immense stretch of deep seabed between Mexico and Hawaii—has been a place of geopolitical calculation and scientific uncertainty. The demand for critical metals has pushed nations and companies to look downward, toward mineral-rich plains in the Pacific. Yet no one truly knew what lived there, how fragile it was, or what would happen if machines began scraping the seafloor clean.

Only now, after a vast international effort, has that mystery begun to yield its secrets.

“Critical metals are needed for our green transition, and they are in short supply. Several of these metals are found in large quantities on the deep-sea floor, but until now, no one has shown how they can be extracted or what environmental impact this would have,” says Thomas Dahlgren, a marine biologist at the University of Gothenburg and one of the leaders of the research project.

The Long Voyage Into Darkness

To uncover the deep sea’s truths, researchers embarked on a monumental effort: five years of coordinated work, 160 days spent at sea, and thousands of samples painstakingly lifted from 4,000 meters down. The research was conducted under the strict guidance of the International Seabed Authority, the global body responsible for overseeing mineral extraction in international waters.

This was more than a single expedition. It was a scientific marathon powered by dozens of specialists, each working to map one of the least explored habitats on Earth. Their task was simple in concept but immense in practice: discover what lives in the deep, record what mining machines do to those communities, and measure the scale of ecological loss.

What they found was both less devastating—and more complex—than many had feared. The number of animals in the machine’s tracks dropped by 37 percent, and species diversity fell by 32 percent. The damage was real, measurable, and far from trivial. But it was not the total collapse some predicted.

“The research required 160 days at sea and five years of work. Our study will be important for the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which regulates mineral mining in international waters,” Dahlgren explains.

A Fragile Empire of 788 Species

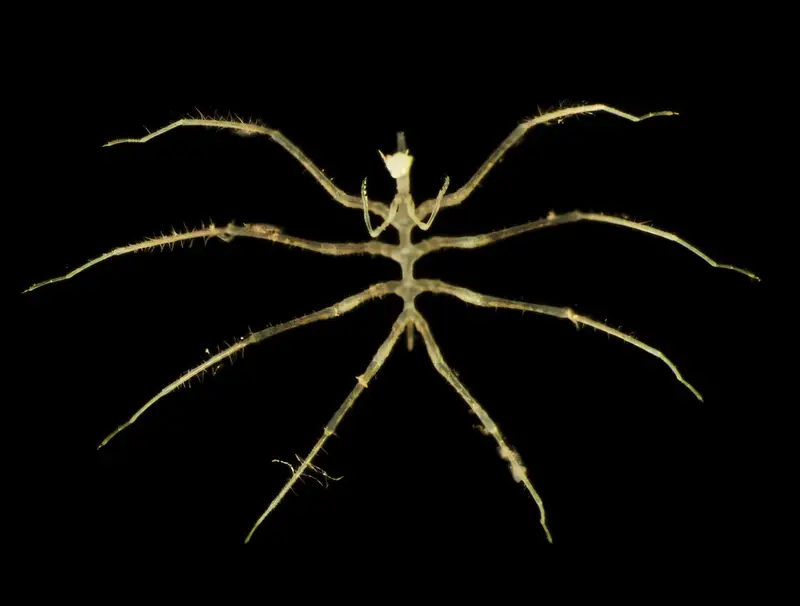

The deep-sea floor, despite its harsh simplicity, turned out to hold extraordinary life. The team collected 4,350 animals larger than 0.3 millimeters—tiny, intricate creatures living in or just above the sediment. From these specimens, the researchers identified 788 species. Nearly all were unknown to science.

Marine bristle worms dominated the samples, alongside crustaceans, snails, mussels, and a wide array of other small but highly specialized organisms. To understand these species, scientists applied molecular tools, turning to DNA to distinguish one tiny life-form from another in a place where morphology alone offers too few clues.

“I have been working in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone for over 13 years, and this is by far the largest study that has been conducted. In Gothenburg, we led the identification of marine polychaete worms. Since most species have not been described previously, molecular (DNA) data was crucial in facilitating studies of biodiversity and ecology on the seabed,” says Dahlgren.

The deep-sea floor may appear barren, but each handful of sediment contains an intricate tapestry of organisms. For comparison, a bottom sample from the North Sea might hold 20,000 animals. The deep-sea sample yields roughly the same number of species, but only about 200 actual specimens—showing just how sparsely distributed life is at these depths. Every individual found there matters. Every loss reverberates through a sparsely populated ecosystem.

A Landscape That Changes Even Without Us

One of the study’s most unexpected findings was how naturally dynamic the deep seabed can be. Despite its reputation as a virtually unchanging environment, the researchers observed that the composition of its communities shifts over time. They believe these fluctuations may be linked to changes in the amount of food falling from the surface waters—fragments of dead plankton, organic debris, and other material drifting downward over thousands of meters.

These natural shifts complicate how scientists interpret the impacts of mining. If species abundance and composition change even without human interference, researchers must disentangle natural variation from industrial disruption. This makes it harder to predict long-term consequences, and even more essential to understand the full range of deep-sea biodiversity.

Exactly how far these species spread across the Pacific’s deep plains remains unknown. Some may inhabit only small pockets of the seafloor. Others might stretch across entire oceanic regions. Without knowing the scale of their distribution, scientists cannot yet judge how vulnerable they are to disturbance.

“It is now important to try to predict the risk of biodiversity loss as a result of mining. This requires us to investigate the biodiversity of the 30% of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone that has been protected. At present, we have virtually no idea what lives there,” says Adrian Glover, senior author from the Natural History Museum of London.

Why This Discovery Matters

The debate over deep-sea mining has been gathering momentum for years, fueled by rising demand for critical metals essential to the global energy transition. The new study does not settle the argument. Instead, it provides the first detailed map of what humanity stands to lose or preserve.

The results show that mining does cause significant ecological damage. Species richness drops, populations shrink, and the tracks left behind by machines leave visible scars in the seafloor community. Yet the decline, though severe, is not total. Some forms of life remain, suggesting that the ecosystem may have some capacity to withstand or recover from disruption.

Still, the full picture remains incomplete. Many species have only just been discovered. Entire protected regions of the Clarion-Clipperton Zone have never been surveyed. And the natural rhythms that shape deep-sea communities are only beginning to be understood.

The work carries global implications. Any decisions made by the International Seabed Authority will influence not just industry and international politics, but the fate of an entire hidden biome on Earth. The species cataloged in this study—most new to science—represent a living record of a world only now emerging into human awareness.

This research matters because it gives humanity its first real chance to make informed choices about the deep sea. It reveals an ecosystem that is neither indestructible nor hopelessly delicate, but one whose fate depends on decisions made today. In a time of rising demand for resources, the study reminds us that the deepest parts of the planet are not empty. They are alive, diverse, and vulnerable—and understanding them is the first step toward protecting them.

More information: Eva C. D. Stewart et al, Impacts of an industrial deep-sea mining trial on macrofaunal biodiversity, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02911-4