For decades, the terahertz range of the electromagnetic spectrum has been a kind of scientific no-man’s land. It sits quietly between microwaves and infrared light, a narrow region rich with promise yet notoriously difficult to measure. Physicists have long imagined the possibilities locked inside this band: lightning-fast communication, harmless package inspection, and exquisitely detailed spectroscopy of organic molecules. But the tools needed to explore this territory with true precision remained stubbornly out of reach.

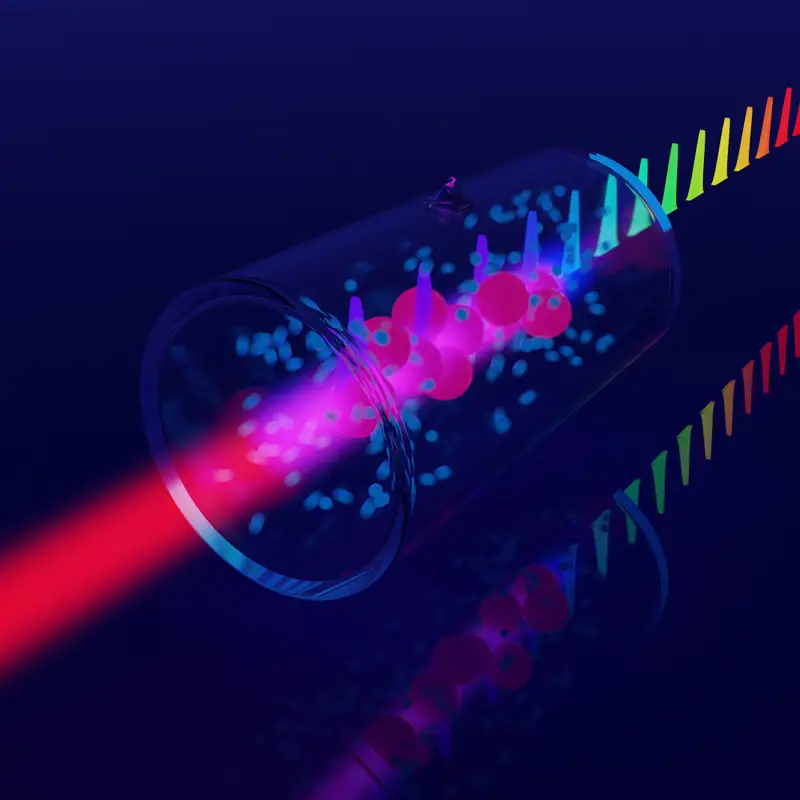

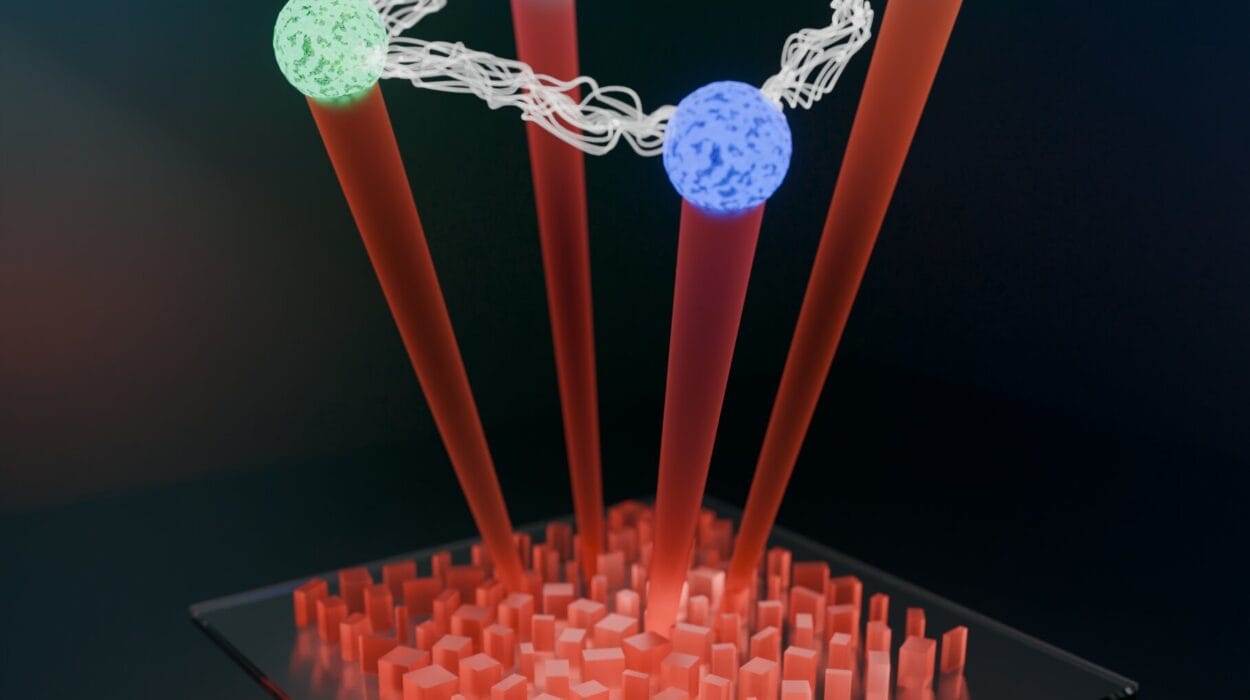

Now, a team from the Faculty of Physics and the Center for Quantum Optical Technologies at the Center of New Technologies, University of Warsaw has changed that landscape. In work described in Optica, they report a technique that not only detects elusive terahertz signals but measures them with unprecedented accuracy. Their secret is something they call a “quantum antenna”—a cloud of rubidium atoms excited into gigantic, fragile Rydberg states. With this tool, they have achieved an experimental milestone: the first-ever precise measurement of a single “tooth” in a terahertz frequency comb.

In the world of precision physics, this achievement represents the opening of a long-locked gate.

The Light Ruler Physicists Have Been Waiting For

To appreciate what the Warsaw team unlocked, one must first understand why frequency combs matter so deeply to modern physics. They are, in essence, rulers made of electromagnetic waves. Instead of millimeter markings, a comb is a sequence of perfectly spaced frequencies, each one a “tooth” that defines a precise point on the spectrum. Such tools have reshaped optical metrology and even earned a Nobel Prize in 2005.

Yet the terahertz domain has remained notoriously difficult. Electronics cannot respond fast enough to resolve individual teeth. Optical techniques cannot reach down to this intermediate band. As a result, although scientists could determine the spacing between teeth and measure the comb’s overall power, one crucial detail remained inaccessible: the power contained in a single terahertz tooth.

This missing piece limited the field. Without it, the terahertz comb could not be used as a reliable reference standard, and its many envisioned applications stalled. The Warsaw team’s achievement fills this gap with a form of precision that modern technology has long struggled to provide.

Rydberg Atoms and the Birth of a Quantum Antenna

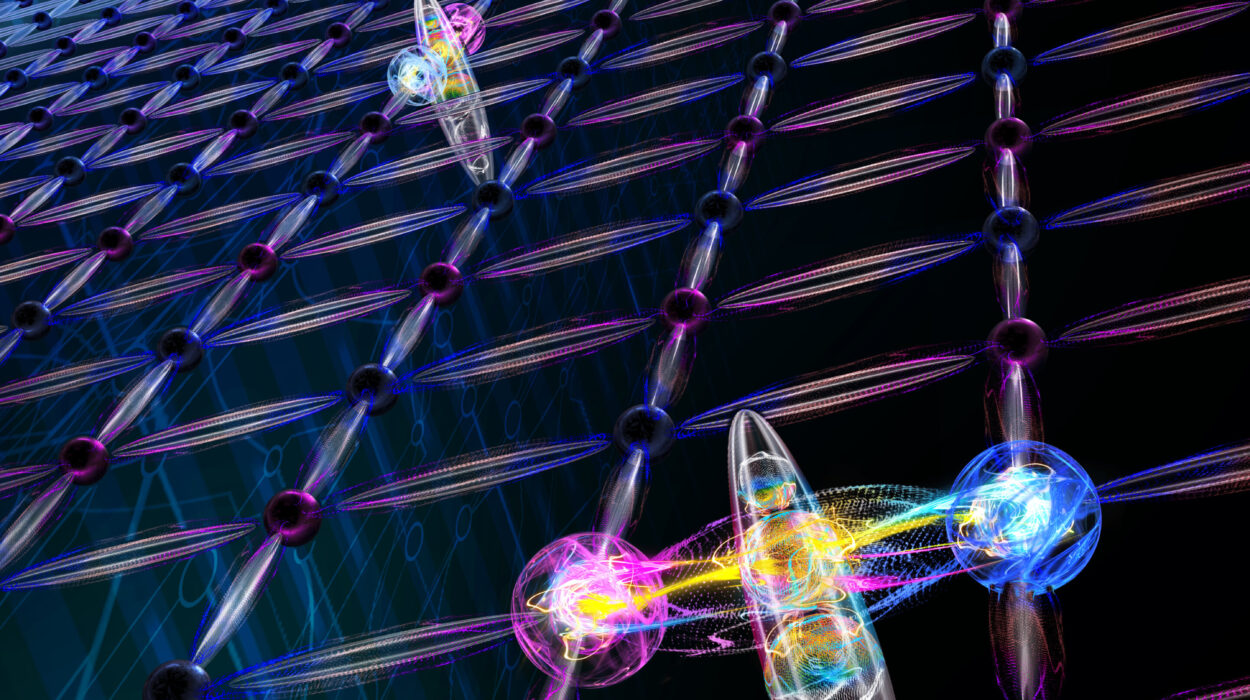

The key to this breakthrough lies in the extraordinary properties of Rydberg atoms. A rubidium atom becomes a Rydberg atom when one of its electrons is pushed to a very high orbit using carefully tuned lasers. The result is a greatly enlarged, extremely sensitive atom whose lone excited electron responds to even the faintest electric fields.

This sensitivity makes a Rydberg atom function like a tiny quantum antenna. More importantly, unlike traditional metal antennas, it requires no external calibration. Its behavior is dictated only by fundamental atomic constants. “Unlike classical antennas, which require laborious calibration in specialized radio laboratories, the atomic-based system is, in a sense, a standard unto itself,” the researchers explain.

The atoms offer another critical advantage: a vast landscape of energy levels that can be scanned almost continuously. With them, a detector can be tuned to frequencies ranging all the way from direct current signals to the terahertz band.

Traditionally, physicists using Rydberg atoms rely on a phenomenon known as Autler–Townes splitting—a precise quantum signature produced when an atom interacts with an electromagnetic field. Because this effect depends only on the atom’s intrinsic properties, it provides an “absolutely calibrated readout,” enabling extremely accurate field measurements.

But there was a problem. On their own, Rydberg atoms struggle to detect the weakest terahertz signals. The terahertz band is so delicate, so faint at times, that even these supersensitive atoms need a boost.

Light as a Messenger for Invisible Waves

To overcome this limitation, the team employed a remarkable hybrid technique developed at the University of Warsaw: converting weak terahertz signals into optical photons. Once converted, those photons can be captured using single-photon counters, among the most sensitive detectors available.

This radio-wave-to-light conversion process provides the missing sensitivity while preserving the all-important calibration capability of the Rydberg atoms. The combination is a fine balance: the quantum antenna identifies and measures the frequency with absolute precision, while the optical detectors reveal signals too faint for any conventional method.

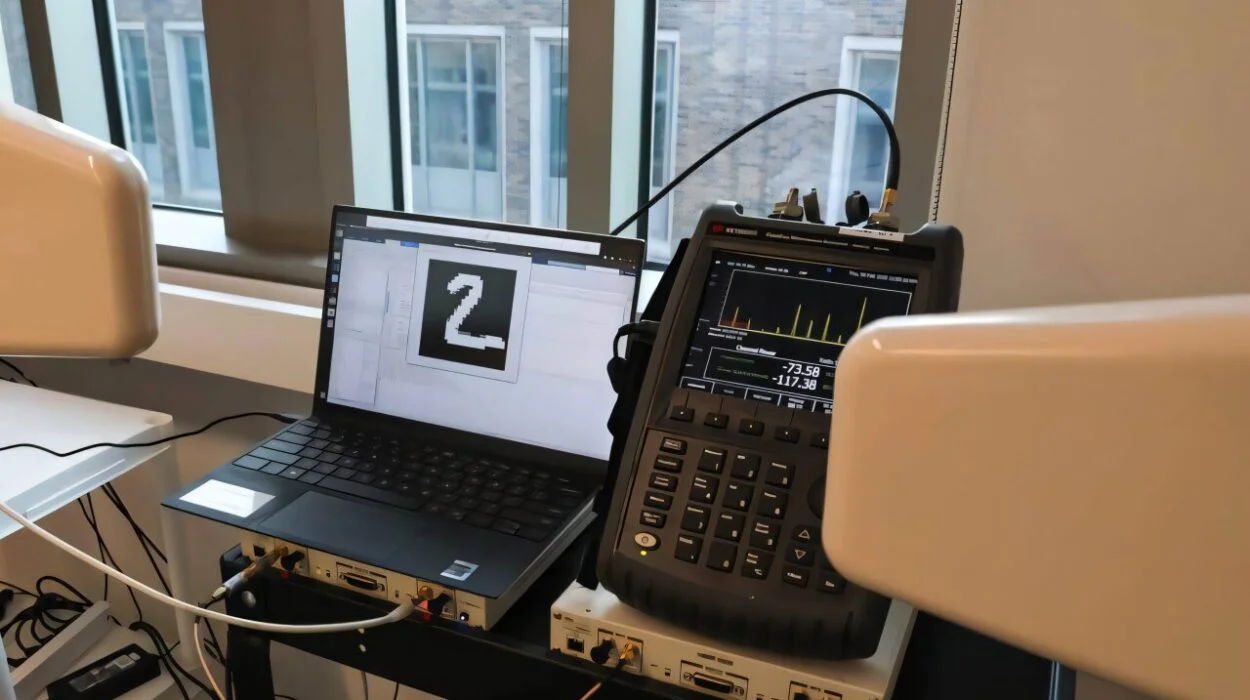

This hybrid approach allowed the team to do what no one had achieved before. They tuned their atomic sensor to a single terahertz comb tooth, measured it precisely, then retuned to the next tooth, and the next, tracing the comb across a remarkably wide range. In the process, they directly calibrated the comb, determining its intensity without relying on any external reference.

What emerged is a full portrait of a terahertz frequency comb—one that scientists have sought for years yet never managed to capture until now.

A New Pathway in Quantum Metrology

The list of contributors—Wiktor Krokosz, Jan Nowosielski, Bartosz Kasza, Sebastian Borówka, Mateusz Mazelanik, Wojciech Wasilewski, and Michał Parniak—underscores the collaborative nature of the effort. But the significance of their work stretches beyond the accomplishment itself.

“The results obtained…are more than just another sensitive detector,” the researchers emphasize. What they developed is a foundation for a new branch of metrology, one able to bring the same revolutionary benefits of optical frequency combs into the terahertz domain.

And, crucially, their device works at room temperature. Many quantum technologies require elaborate cooling setups involving liquid helium or vacuum-sealed cryogenic chambers. By contrast, the Warsaw team’s solution demands nothing exotic. This makes it not only a scientific milestone but a practical one—far more accessible for engineering, commercial development, and future deployment.

Why This Discovery Matters

Terahertz radiation sits in a region of the spectrum that has remained technologically underdeveloped despite its enormous promise. Precise measurement tools are the foundation of any new technology, and the absence of such tools has slowed the emergence of terahertz-based applications. Without a reliable standard, every device built for this frequency range lacked a cornerstone of calibration.

The Warsaw breakthrough provides that cornerstone. It establishes a way to read the terahertz spectrum with unprecedented clarity, unlocking ultrasensitive spectroscopy, enabling next-generation communication technologies, and offering a path toward new imaging systems that reveal the structure of organic materials without harmful radiation.

Equally important, it charts a path for the creation of reference measurement standards at terahertz frequencies—standards that could shape the future of wireless networks, medical diagnostics, and quantum sensing alike.

By transforming fragile, swollen atoms into quantum antennas, the researchers have opened a new window onto one of the most intriguing and technologically promising regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. Their achievement marks the beginning of a new era in terahertz science—one in which the tools of precision finally match the immense potential of the waves they seek to measure.

More information: Wiktor Krokosz et al, Electric-field metrology of a terahertz frequency comb using Rydberg atoms, Optica (2025). DOI: 10.1364/optica.578051