The quiet revolution in modern technology is not happening in distant data centers humming with servers. It is happening at the edges of networks, where drones scan forests, robots glide through warehouses, and sensors watch over city streets. These devices are no longer just collecting information. Increasingly, they are expected to decide what that information means, and to do so instantly, without waiting for instructions from faraway computers.

This shift toward edge computing promises faster responses, lower energy use, and greater independence from centralized systems. But it also exposes a stubborn problem. The intelligence we want these small devices to have is growing rapidly, while the space, power, and memory inside them remain painfully limited.

The result is a technological tension that has shaped how artificial intelligence works outside the cloud. And now, researchers at Duke University believe they may have found a way to release it.

The Weight of Intelligence in Tiny Machines

Modern AI models are powerful because they are large. They rely on vast collections of numerical values, called model weights, that guide how data is interpreted. These weights allow an AI system to recognize images, understand signals, or make decisions based on patterns.

For a small, battery-powered device, carrying all of that intelligence is a heavy burden. Storing an entire AI model locally demands memory the device may not have. Running it digitally requires continuous computation, draining batteries and generating heat.

There has long been an escape route. Instead of running the model on the device, the data can be sent to the cloud, processed there, and returned with an answer. This avoids hardware limitations, but at a cost. The back-and-forth introduces delay, consumes energy through wireless transmission, and raises concerns about security and reliability.

Engineers have learned to live with these trade-offs. But they are far from ideal, especially as devices are asked to respond faster and operate longer in the field. The question has lingered for years. Is there a way to give edge devices access to powerful AI without forcing them to carry its full weight?

A Third Path Appears in the Air

The answer proposed by Duke researchers does not sit on a chip or in a server. It travels through the air.

Their approach, called Wireless Smart Edge networks, or WISE, offers a third option that avoids the pitfalls of both local storage and cloud offloading. Instead of loading AI models onto devices or sending data away for processing, WISE embeds the intelligence directly into radio waves transmitted from nearby base stations.

In this system, a base station holds the full AI model. It broadcasts a radio frequency signal that encodes the model’s weight values. Edge devices receive this signal and combine it with their own input data. The key insight is that part of the AI computation happens naturally during this interaction, without ever being translated into digital code.

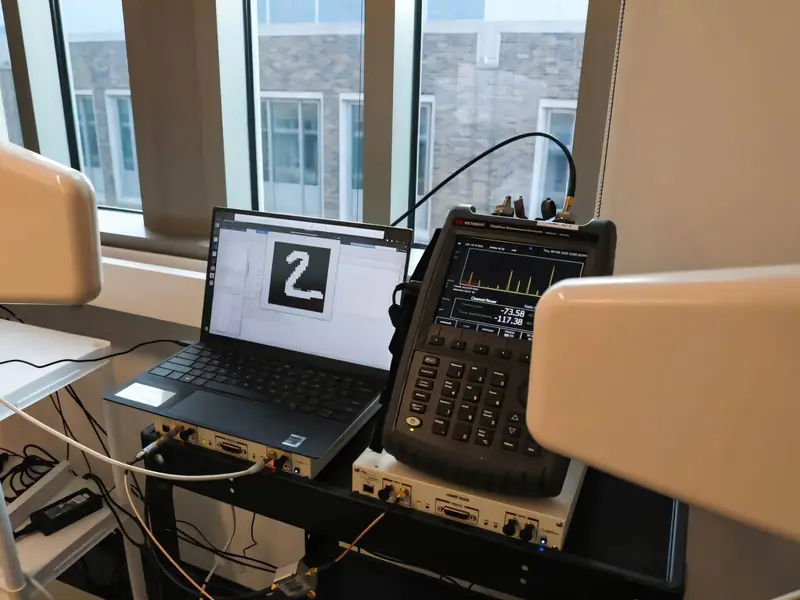

The research, published online in Science Advances on January 9, is led by Tingjun Chen, the Nortel Networks Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Duke University, in collaboration with Dirk Englund’s team at the MIT Research Laboratory of Electronics.

It is an idea that reframes what wireless communication can do. Instead of merely delivering data, the network itself becomes a participant in the computation.

Letting Physics Do the Math

At the heart of WISE is a concept known as in-physics analog computing. To understand its significance, it helps to consider how most computing works today.

Traditional digital computing relies on binary code, reducing information to ones and zeros. Data is shuttled into a processor, where long sequences of mathematical operations are executed step by step. This method is reliable and precise, but it is not gentle on small devices with limited energy.

In-physics computing takes a different approach. Rather than forcing every calculation through a digital processor, it allows the natural behavior of physical systems to perform part of the math.

In WISE, when the broadcast radio signal reaches an edge device, its existing radio hardware goes to work. Components such as passive frequency mixers combine the incoming signal with the device’s own data. This mixing process can approximate the multiplication operation that lies at the core of most deep learning models.

Crucially, this computation happens directly in the RF or analog domain, before any digital processing is required. The radio waves themselves carry information in a form optimized for the computation, completing a key step without consuming the energy typically associated with digital math.

“We’re taking advantage of computations that common, miniaturized electronics already gives us,” Chen explained. Instead of forcing every step onto a chip built for digital logic, the system lets physics handle part of the workload.

Intelligence Without the Baggage

Because edge devices in WISE do not store the full AI model or execute it digitally, they sidestep the largest barriers to edge intelligence. Memory demands shrink. Energy consumption drops. The need for powerful processors fades.

For Zhihui Gao, a Ph.D. student in Chen’s lab and the lead author of the study, this shift opens doors for devices that have long been constrained by their size.

Drones, cameras, and traffic sensors all generate data continuously. Yet many of them struggle to run advanced models that could help them interpret what they see in real time. WISE shows how these devices could tap into powerful AI without relying on heavy chips or distant servers.

“Technology is moving toward smaller devices that can do more than ever before,” Gao said. “With WISE, we have shown how devices can run on powerful AI without relying on heavy chips or distant servers.”

In experiments, the system achieved nearly 96 percent image classification accuracy while using more than an order of magnitude less energy than leading digital processors. The result suggests that efficiency does not have to come at the expense of performance.

Built on What Already Exists

One of the most striking aspects of WISE is how little new hardware it requires. The approach is designed to work with existing wireless infrastructure.

Base stations already deployed for 5G, emerging 6G, or even WiFi routers could be augmented to broadcast AI models with relatively small adjustments. On the device side, the necessary components are already present. Everyday wireless electronics contain frequency mixers capable of performing the in-physics computation.

“We’re not adding exotic components or creating entirely new hardware,” Gao noted. “We’re reusing features that are widely deployed and don’t consume extra energy.”

This compatibility lowers the barrier to adoption and hints at how seamlessly computation and communication could blend in future networks.

Early Steps and Open Horizons

Despite its promise, WISE remains at an early stage. The current prototype operates over short distances. Extending its range would require stronger transmissions or integration with next-generation wireless equipment.

There are also challenges in scaling the idea. Broadcasting multiple AI models at the same time would demand careful management of time, frequency, and spatial resources, or access to additional spectrum bandwidth.

Yet the researchers see wide-ranging possibilities. A single base station could support a swarm of drones during a search and rescue mission, distributing intelligence across the group. Traffic cameras could coordinate intersection signals, responding dynamically without relying on distant servers.

Each of these scenarios points to a future where intelligence is not locked inside devices or centralized in the cloud, but shared fluidly across the airwaves.

Why This Research Matters

WISE represents more than a clever technical workaround. It challenges the traditional separation between communication and computation, suggesting that the networks connecting our devices can also help them think.

By embedding AI model weights into radio waves and letting physics perform part of the computation, the researchers have outlined a path toward energy-efficient edge AI that scales with the growing demands of modern technology. This approach could allow small devices to act faster, last longer, and operate more securely, all while reducing reliance on distant servers.

“This is the next step in wireless technologies becoming as powerful as wired ones,” Chen said. Beyond simply delivering data, future networks may distribute intelligence itself.

In a world increasingly shaped by autonomous decisions made at the edge, that shift could redefine how machines perceive, respond to, and ultimately share our environment.

Study Details

Zhihui Gao et al, Disaggregated Machine Learning via In-Physics Computing at Radio Frequency, Science Advances (2026). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adz0817. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adz0817