Albert Einstein entered the world quietly on March 14, 1879, in the city of Ulm in the Kingdom of Württemberg, part of the German Empire. His arrival into the world was not marked by the kind of grand heralding one might expect of a man destined to alter our understanding of time and space. In fact, his parents, Hermann and Pauline Einstein, were more worried than elated. Young Albert’s head appeared unusually large, and his speech came late—so late that the family feared something might be wrong. Little did they know that behind those wide, silent eyes brewed a mind that would eventually reach out and touch the fabric of the cosmos.

Albert’s early years were spent in Munich, where his father and uncle ran a small electrical engineering company. The household fostered a deep appreciation for learning, though not in the conventional sense. While young Albert disliked the rigidity of German schools, he found deep pleasure in exploring mathematics and science at his own pace. He taught himself Euclidean geometry at age twelve and began exploring Kant’s philosophical ideas not long after. The boy who rarely spoke was, in truth, listening deeply to the world—analyzing, understanding, questioning.

The early silence of his life would later echo in the clarity and calmness with which he would express ideas that shook the scientific world.

The Seeds of Rebellion

By the age of fifteen, Albert Einstein had already begun to rebel—not against his family, but against a world that felt too confining. The strict discipline of German schooling clashed violently with his independent mind. In one letter, he later recalled the schoolmasters treating students like soldiers, not scholars. In 1894, his father’s business failed, prompting the family to move to Italy. Albert followed a few months later, leaving school behind without a diploma. It was not an impulsive departure—it was strategic and intentional.

Einstein spent time in Milan and Pavia, and though he was officially out of school, his mind was never more active. He roamed libraries, read scientific journals, and taught himself advanced mathematics. Eventually, he decided to enroll at the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich. At just sixteen years old, he failed the entrance exam—not because he lacked intelligence, but because he had not studied the humanities subjects in which he was tested. The failure was only temporary. He spent a year at a Swiss school to round out his education and successfully passed the exam the following year.

In Zurich, Einstein found the kind of intellectual freedom he had been yearning for. He studied physics and mathematics but often found himself at odds with his professors, many of whom thought him undisciplined. Einstein’s approach to learning was not about regurgitating information but about understanding deeply and fundamentally. He often skipped classes and instead studied the great scientific thinkers of the past—Newton, Maxwell, Helmholtz—and dreamed of the future.

Love, Work, and Isolation

During his time in Zurich, Einstein met a fellow physics student, Mileva Marić, the only woman in his class. Their intellectual companionship soon turned romantic. The relationship was fraught with both affection and difficulty, made more complicated by the era’s gender expectations and their diverging life paths. They would later marry and have two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard, but the marriage would not survive the pressures of Einstein’s growing fame and personal struggles.

After graduating in 1900, Einstein faced an unexpected wall: no university wanted him. His reputation as a poor student of authority and his unconventional methods did not help. For two long years, he wandered the academic desert, unable to find a permanent job. He tutored children, depended on friends for money, and grew increasingly disillusioned. Then, in 1902, a friend helped him secure a job at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. It was not academia, but it was steady, and more importantly, it left his evenings free for thinking.

Einstein would later say that the patent office was a “worldly cloister” where he could think without interruption. That modest office, surrounded by technical applications and descriptions of machines, became the unlikely birthplace of one of the most revolutionary periods in scientific history.

The Miracle Year

In 1905, Albert Einstein, still an unknown clerk in a patent office, published four papers that would change the world. This year would later be called his Annus Mirabilis, or Miracle Year.

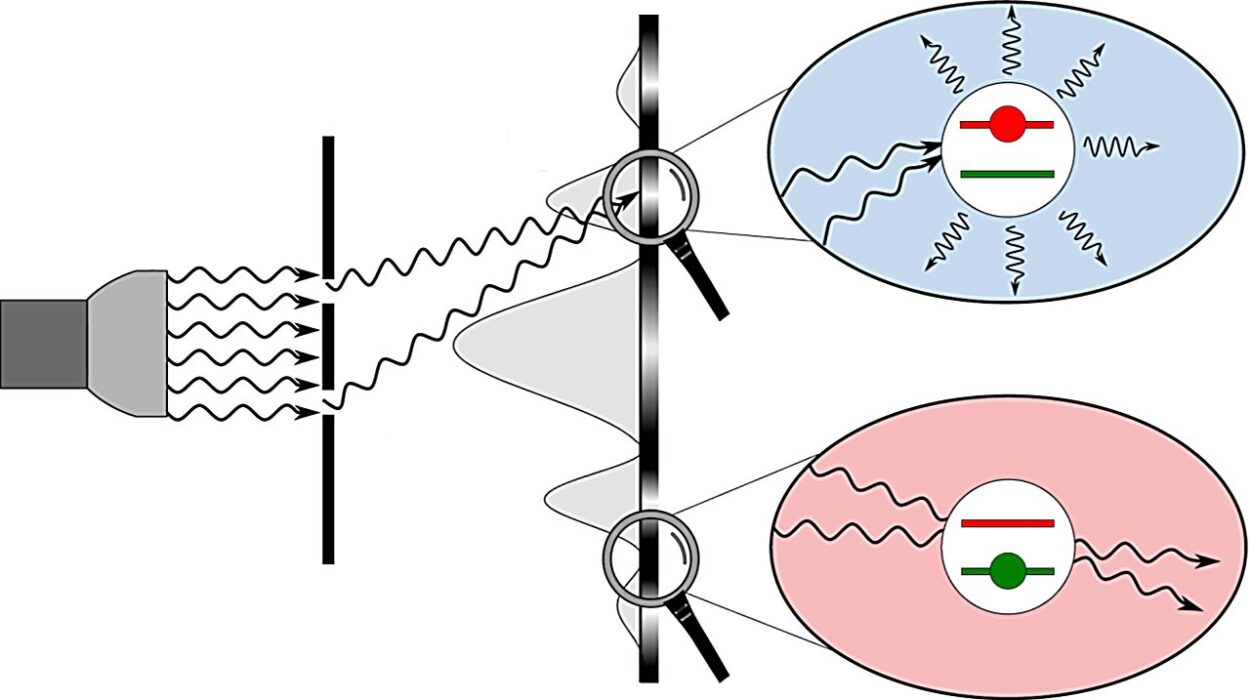

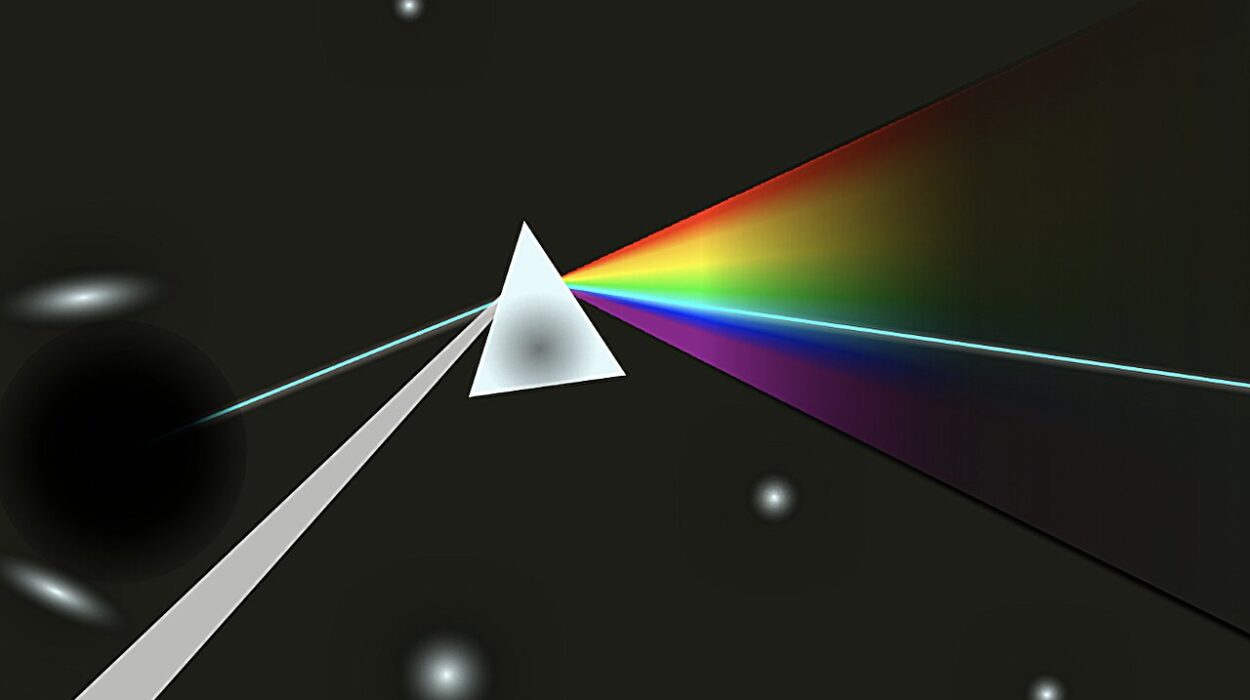

The first paper addressed the photoelectric effect, suggesting that light could behave as both a wave and a stream of discrete particles called quanta. This paper, though it wouldn’t earn him immediate fame, would later win him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921. It laid the groundwork for quantum mechanics, a field Einstein himself would later find deeply troubling.

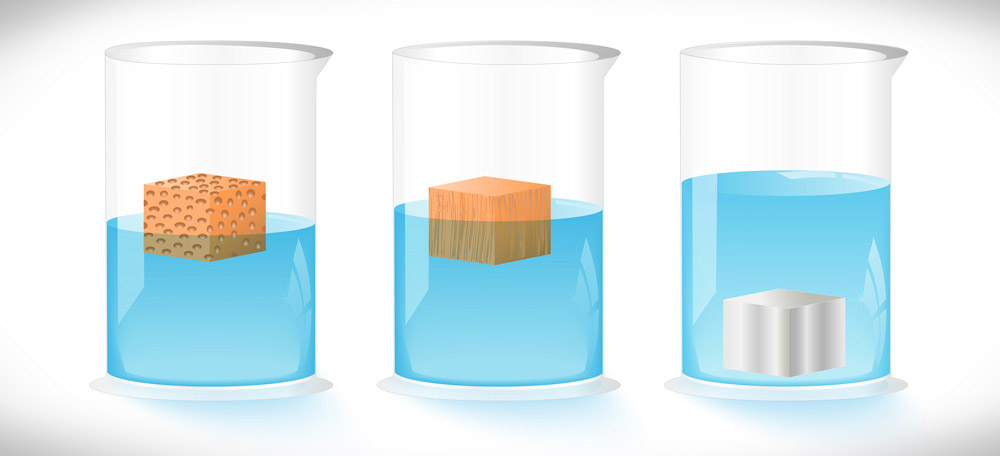

The second paper offered experimental proof for the existence of atoms by explaining Brownian motion—the jittery movement of particles suspended in liquid.

The third and fourth papers laid out the Special Theory of Relativity, introducing the mind-bending concept that time and space are not fixed but relative to the observer. He argued that the speed of light is constant and that time slows down for objects in motion. These ideas were not speculative or poetic; they were wrapped in precise mathematics and physical principles. They shook the foundations of Newtonian mechanics and reshaped how we view the universe.

Out of obscurity, a new light emerged. The scientific world could no longer ignore the soft-spoken man with the wild hair and fierce intellect.

Rising Star in a Changing World

Einstein’s rise through the academic ranks was rapid after 1905. By 1909, he secured a position at the University of Zurich. A series of posts followed—at the German University in Prague, the ETH in Zurich, and finally, in 1914, the prestigious Prussian Academy of Sciences in Berlin. There, he continued refining his ideas about space and time, gravitating toward what would become his crowning achievement: the General Theory of Relativity.

But Berlin also brought personal turmoil. His marriage to Mileva was crumbling, and though they had two children, the emotional distance between them widened. In 1919, they divorced. That same year, Einstein married his cousin Elsa Löwenthal.

While his personal life was marked by complexity, his intellectual life soared. In 1915, after years of struggle and mathematical refinement, he unveiled the General Theory of Relativity. Unlike the special theory, which dealt with observers in constant motion, general relativity addressed gravity itself—not as a force, as Newton described, but as a warping of space-time by mass. Massive objects like the sun, Einstein proposed, bend the very fabric of the universe, curving the paths that objects follow.

A Universe Confirmed

Einstein’s theory remained just that—a theory—until 1919, when a British expedition led by Sir Arthur Eddington observed a solar eclipse and confirmed that starlight passing near the sun was indeed bent, just as Einstein predicted. The newspapers declared him a genius. The world, still recovering from the horrors of World War I, was hungry for a new kind of hero—a thinker, not a soldier.

Overnight, Albert Einstein became a household name. His photograph appeared in newspapers around the globe. Children wrote him letters. Scientists visited him from far and wide. Fame brought both admiration and unease. Einstein never relished the spotlight, yet he used his growing influence to speak out on the issues that mattered to him: pacifism, civil rights, education, and, later, the threat of fascism.

He also began to feel isolated in the scientific community. While general relativity was embraced, Einstein’s increasingly vocal skepticism of the emerging quantum mechanics—especially its embrace of uncertainty—put him at odds with younger physicists like Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg. “God does not play dice with the universe,” he famously said, a sentiment met with disagreement from Bohr, who replied, “Einstein, stop telling God what to do.”

Exile and Renewal

The 1930s brought storm clouds that no theory could predict away. With the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party, Einstein, a Jew and outspoken critic of nationalism, became a target. He left Germany in 1933, never to return. That same year, he accepted a position at the newly created Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. It would be his home for the rest of his life.

In America, Einstein became a paradox—a global icon who sought a quiet life. He wore the same threadbare clothes day after day, refused socks, and wandered the streets of Princeton like a local sage. Yet his mind remained electric. He continued searching for what he called a “unified field theory,” an attempt to merge gravity and electromagnetism into a single framework. Though he never succeeded, he never stopped trying.

But the world he fled from was not done with him. In 1939, fellow physicist Leo Szilard convinced Einstein to write a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning that Germany might be developing an atomic bomb. That letter helped catalyze the Manhattan Project, though Einstein himself was never involved in the bomb’s construction. When Hiroshima and Nagasaki were destroyed in 1945, Einstein was heartbroken. He later called the letter “the one great mistake in my life.”

He spent his final years advocating for nuclear disarmament, world peace, and civil rights. He spoke out against McCarthyism and racism, lending his voice and prestige to causes he felt were just. He supported W.E.B. Du Bois, Albert Schweitzer, and Bertrand Russell, among others. Though he had once believed in a world governed by rational laws, he now confronted a human world often governed by irrational fears.

The Final Equation

In the quiet of Princeton, Einstein aged gracefully. He became a symbol of curiosity, a figure who embodied both the brilliance and the burden of scientific genius. Visitors often expected fireworks but found instead a gentle man with a mischievous smile, someone more interested in asking questions than in claiming answers.

On April 17, 1955, he experienced internal bleeding caused by the rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. When offered surgery, he refused, saying, “I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially.” He died the following morning at the age of 76.

Even in death, Einstein’s body could not rest without controversy. The pathologist who performed the autopsy, Dr. Thomas Stoltz Harvey, removed Einstein’s brain without permission, hoping to uncover the physical source of genius. The brain was preserved, dissected, and studied for decades, but the true source of Einstein’s brilliance would not be found in folds or neurons. It existed in the questions he dared to ask and the truths he helped humanity to see.

Legacy Beyond the Equations

Albert Einstein’s legacy cannot be contained in a single theory, paper, or prize. He redefined not only how we understand the universe but how we understand our place in it. His insights opened the doors to modern cosmology, GPS technology, black hole research, and quantum computing. Yet he also left behind something even more enduring: a model of intellectual courage.

He showed that one could question the deepest assumptions of reality with a chalkboard and a dream. He proved that wonder and rigor, far from being opposites, could live in harmony. And he reminded the world that knowledge was not a privilege of the few, but the birthright of all who dare to imagine.

In his own words: “The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion that stands at the cradle of true art and true science.”

Albert Einstein lived not just a life of the mind, but a life of meaning. He taught us that time bends, light curves, and gravity pulls not just on bodies—but on hearts.