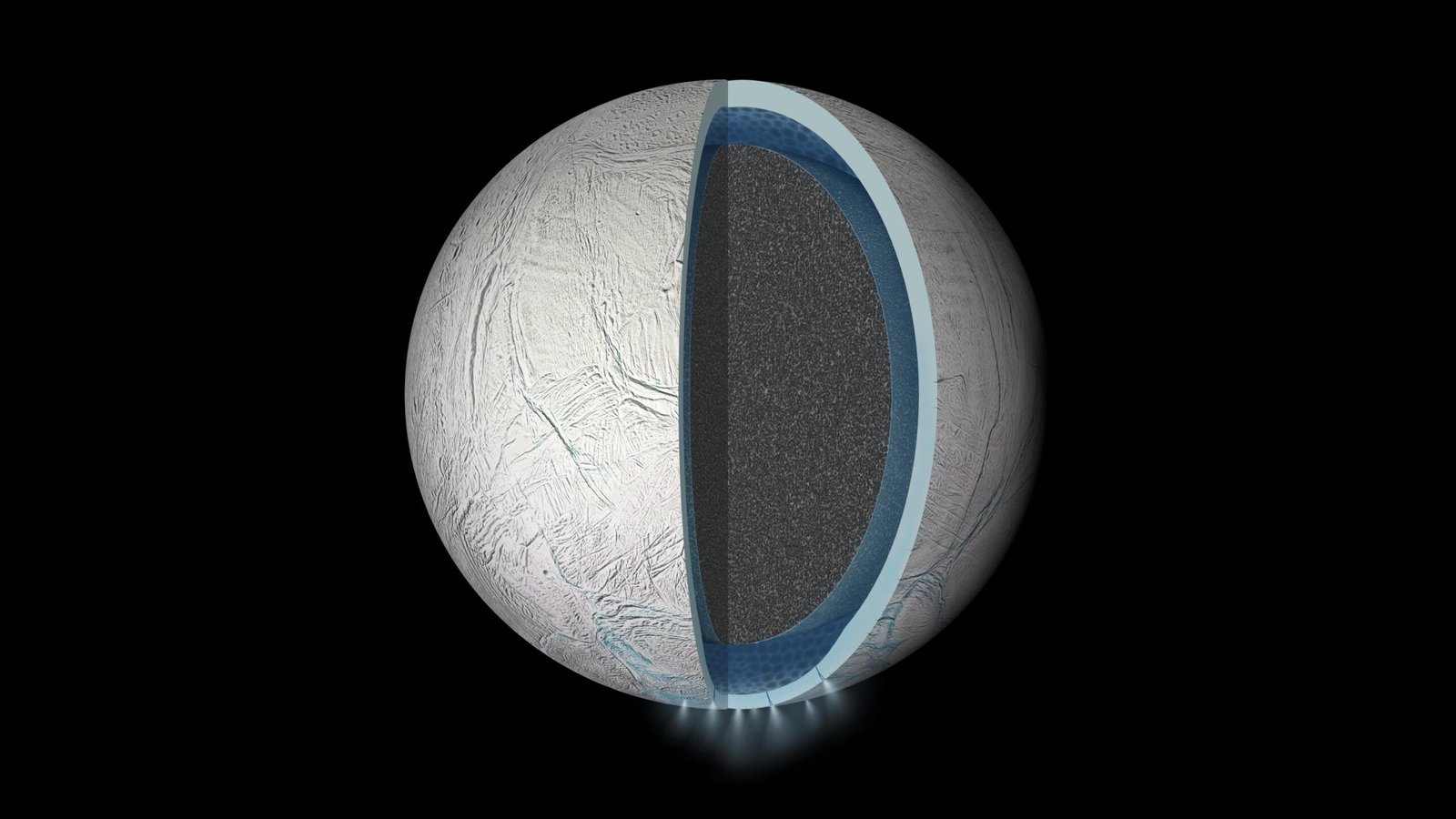

Far from Earth, wrapped in ice and circling Saturn in quiet obedience, Enceladus once seemed like just another frozen moon. Then it began to speak.

From cracks near its south pole, towering plumes of water vapor and ice burst into space, scattering material along its orbit and feeding one of Saturn’s shimmering rings. When NASA’s Cassini spacecraft flew through those plumes, it didn’t just detect water. It found organic compounds, chemical ingredients that, on Earth, are woven into the fabric of life itself.

For years, these discoveries lingered as tantalizing hints rather than clear answers. Were these molecules born inside Enceladus, in a hidden ocean beneath the ice, or were they ancient leftovers, trapped there since the moon’s formation? Now, through carefully designed experiments on Earth, researchers believe they have moved closer to an answer.

Cassini’s Fleeting Glimpse Into an Invisible Ocean

Between 2004 and 2017, Cassini made repeated passes through Saturn’s E-ring, sampling particles launched from Enceladus’ surface. Its instruments, including mass spectrometers and an ultraviolet imaging spectrograph, revealed a surprising chemical richness.

The data showed everything from simple carbon dioxide to longer hydrocarbon chains, molecules that on Earth serve as essential precursors to complex biomolecules. Beneath the moon’s thick ice shell, astronomers widely predict a liquid water ocean, especially in the south polar region where the plumes originate. The implication was hard to ignore. A cold moon, hundreds of millions of kilometers away, might host the raw ingredients needed for life.

Yet fascination alone could not resolve the mystery. Cassini had measured what was there, but not how it came to be.

The Question That Wouldn’t Go Away

The presence of organic molecules sparked excitement, but also unease. As Max Craddock of the Institute of Science Tokyo explains, it remained unclear whether these compounds were actually produced inside Enceladus or simply inherited from ancient material that formed the moon.

Earlier laboratory studies had explored hydrothermal organic synthesis, often in the context of early Earth or comets. But Enceladus is neither Earth nor a comet. Its environment is shaped by a thick ice shell, repeated cycles of freezing and heating, and powerful tidal forces from Saturn that stretch and squeeze the moon as it orbits.

Without experiments designed specifically for this setting, scientists were left with unanswered questions. How does the ice shell affect chemical reactions in the ocean below? What role do simple compounds play in building larger ones? And if Enceladus’ chemistry were recreated in a laboratory, would it resemble what Cassini actually saw?

Without a bridge between laboratory chemistry and spacecraft data, interpretation stalled.

Building an Ocean Inside a Reactor

To construct that bridge, Craddock and his colleagues chose a different path. Instead of starting with spacecraft measurements and trying to infer chemistry backward, they attempted something bolder. They recreated Enceladus’ subsurface ocean conditions directly in the lab.

The first step was choosing the right ingredients. The team assembled a chemical mixture based on the simple compounds Cassini detected in the plumes, including ammonia and hydrogen cyanide. These were not exotic additions, but substances already known to exist on the moon.

Next came the environment. Using a high-pressure reactor, the researchers subjected the mixture to repeated cycles of heating and cryogenic freezing. These cycles were designed to mimic the stresses Enceladus experiences as Saturn’s gravity kneads the moon, a process astronomers believe triggers hydrothermal activity beneath the ice.

In such conditions, smaller molecules gain opportunities to collide, react, and combine, potentially forming more complex organic structures.

But creating the chemistry was only half the challenge. The team also needed to see their results the way Cassini would have seen them.

Seeing Through Cassini’s Eyes

After the reactions ran their course, the researchers analyzed the products using a laser-based mass spectrometer built to mimic Cassini’s Cosmic Dust Analyzer. This step was crucial. It allowed a direct comparison between laboratory-generated molecules and the spacecraft’s measurements, closing the long-standing gap between theory and observation.

When the data emerged, it told a compelling story.

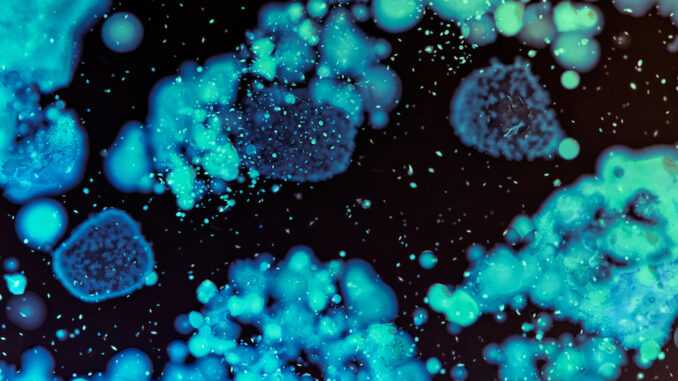

The artificial hydrothermal reactions had produced a wide variety of complex organic molecules. Among them were amino acids, aldehydes, and nitriles, all chemical families closely tied to biological processes on Earth. The freezing cycles themselves appeared to play an important role, helping generate simpler amino acids such as glycine.

Many of these products closely matched the smaller organic compounds Cassini had detected while flying through Enceladus’ plume.

For the first time, scientists could see how the moon’s hidden ocean might naturally produce the chemistry observed in space.

The Missing Pieces That Spark New Questions

The results were striking, but not complete. Some larger molecules detected by Cassini did not appear in the laboratory experiments. Their absence opens new possibilities rather than closing the case.

One explanation is that Enceladus’ subsurface ocean may host hotter or catalyzed reactions that the experimental setup could not reproduce. Another is that some material truly is ancient, inherited from the moon’s earliest days and preserved within its icy shell.

Rather than weakening the findings, these gaps sharpen them. They suggest that Enceladus’ chemistry is not simple or static. It may be layered, dynamic, and influenced by processes still beyond our experimental reach.

What the experiments clearly demonstrate, however, is that Enceladus’ ocean is both chemically rich and actively capable of generating the building blocks of life.

A Guide for the Explorers Yet to Come

Beyond revealing what Enceladus might be doing today, the study offers something equally important. It provides guidance for how future missions should interpret plume measurements.

As Craddock notes, the findings underscore the need for instruments capable of verifying amino acids and determining whether complex organics reflect ongoing internal chemistry or ancient material. Such distinctions are essential for evaluating the moon’s habitability and understanding how chemistry in ocean worlds might progress toward life.

At present, there are no dedicated missions planned for Enceladus or Saturn’s rings. That makes laboratory studies like this more than academic exercises. They are one of the few ways to keep probing the moon’s hidden ocean using the data already collected and the tools available on Earth.

Why This Research Matters

Enceladus is a reminder that worlds capable of complex chemistry do not announce themselves loudly. Its ocean lies buried beneath ice, invisible to telescopes and unreachable by drills. Yet through plumes, particles, and careful experimentation, its story is beginning to emerge.

By showing that the organic molecules detected by Cassini can form under Enceladus-like conditions, this research strengthens the idea that the moon is not just passively carrying chemical ingredients, but actively producing them. It transforms Enceladus from a place that merely contains organic compounds into a world where chemistry is alive with possibility.

In doing so, it reshapes how scientists think about ocean worlds, both within our solar system and beyond. If life’s building blocks can arise in the dark ocean of a small icy moon, then the search for habitability no longer belongs only to planets bathed in sunlight. It extends into the cold, hidden places, where chemistry quietly works, waiting to be understood.

Study Details

Maxwell L. Craddock et al, Laboratory simulations of organic synthesis in Enceladus: Implications for the origin of organic matter in the plume, Icarus (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2025.116836