For decades, physicists have imagined a strange kind of light that behaves less like a fleeting flash and more like a stubborn traveler. It moves forward without spreading, without dissolving, without forgetting what it is. It can even collide with another wave and come out the other side unchanged, as if nothing happened. This idea has lived comfortably in equations and theory, but not in laboratories. Until now.

In Italy, a team of physicists has created something never before seen in an experiment: a lump soliton, an extraordinarily stable packet of light that can move through three-dimensional space and keep its shape intact. Led by Ludovica Dieli at Sapienza University of Rome, the researchers finally turned a fifty-year-old theoretical prediction into a physical reality. Their work appears in Physical Review Letters, marking a milestone in the study of nonlinear waves.

This is not just a new kind of light pattern. It is a long-awaited confirmation that certain mathematical ideas about stability, order, and resilience can survive outside the chalkboard, inside a real material, under real experimental conditions.

When Waves Learn How to Remember

To understand why this achievement matters, it helps to start with a simple truth about waves. Most waves forget themselves. A ripple on water spreads out and fades. A burst of sound disperses into the air. Light beams diffract, blur, and distort as they travel. Information carried by waves is fragile.

A soliton is different. It is a localized wave packet that, in theory, can maintain its shape indefinitely as it moves forward. Even more remarkably, when a soliton encounters another wave, it does not dissolve into chaos. Instead, it passes through and emerges intact. This unusual behavior depends on a powerful mathematical property known as integrability.

Integrability appears in certain nonlinear equations that contain many conserved quantities, such as energy and momentum. These quantities remain constant as the system evolves, acting like anchors that hold the wave together. Because of this, integrable solitons are far more resistant to distortion and turbulence than ordinary waves.

Physicists have managed to create truly integrable solitons in laboratories before. But there was always a catch. Those solitons could only exist in one dimension, traveling along a single straight line. The real world, however, is not one-dimensional.

A Theory Waiting Since 1970

Back in 1970, two Soviet physicists proposed a bold extension of soliton theory. They introduced a mathematical model showing how solitons could propagate through three-dimensional space while preserving their stability. The resulting solution became known as a lump soliton, described by the Kadomtsev-Petviashvili equation, often called the KP equation.

On paper, the lump soliton was elegant and compelling. It behaved exactly as physicists hoped a multidimensional soliton would behave. But turning the KP equation into a real physical system proved extraordinarily difficult.

As Dieli explains, “research on the lump soliton continues to lack experimental observation due to the restrictive conditions required by the KP equations to apply to a real physical system.” Despite decades of progress in nonlinear wave physics, lump solitons remained confined to theory. They were a promise without proof.

A Crystal That Could Be Persuaded

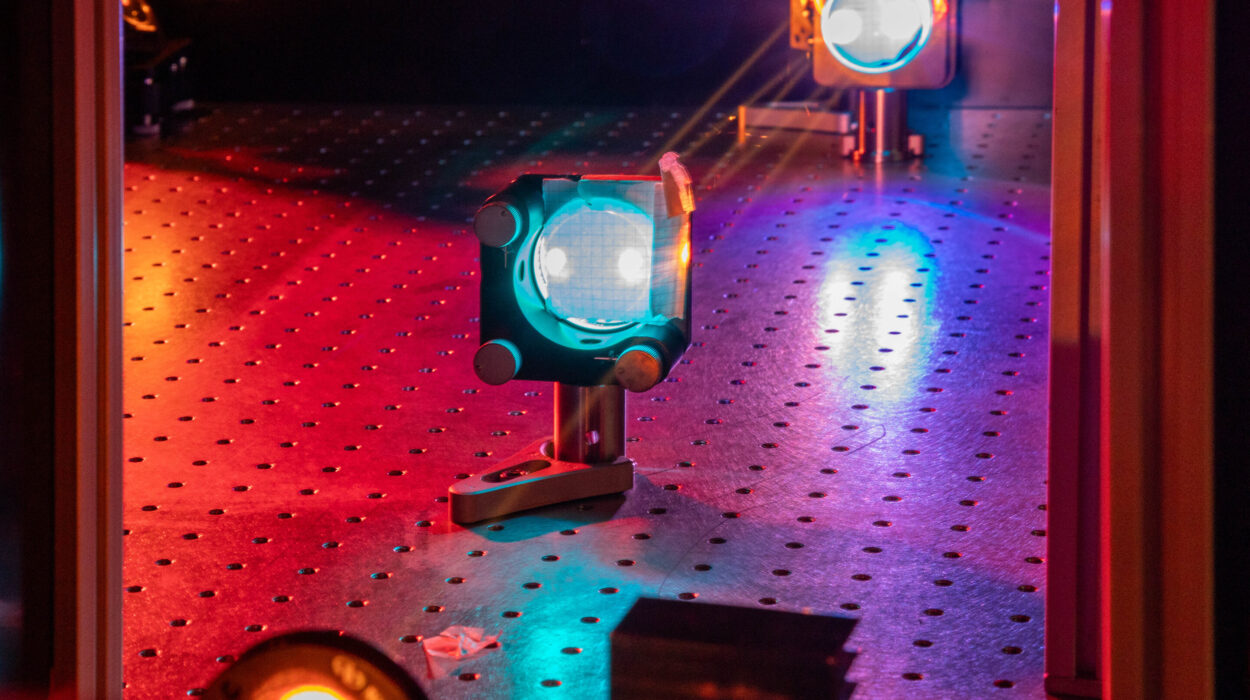

The breakthrough came from an unusual choice of material and an even more unusual level of control. Dieli’s team worked with a strontium-barium niobate crystal, a material with strong photorefractive properties. Inside this crystal, light does not simply pass through. Instead, its propagation depends on the light’s own intensity.

This intensity-dependent behavior allowed the researchers to shape how light moves through the crystal. By applying an external voltage, they could fine-tune the crystal’s response with precision. The voltage transformed the optical field inside the crystal into what physicists call a photon fluid, a system where light flows and responds much like a conventional fluid.

In this environment, light and medium interact in a tightly coupled way. The beam influences the fluid, and the fluid influences the beam. This mutual interaction is what gives rise to the nonlinear response required for solitons to exist.

Building the Perfect Beginning

Creating a soliton is not just about letting light propagate. It is about starting with exactly the right conditions. Any small mismatch between theory and experiment can cause the wave to distort, collapse, or disperse.

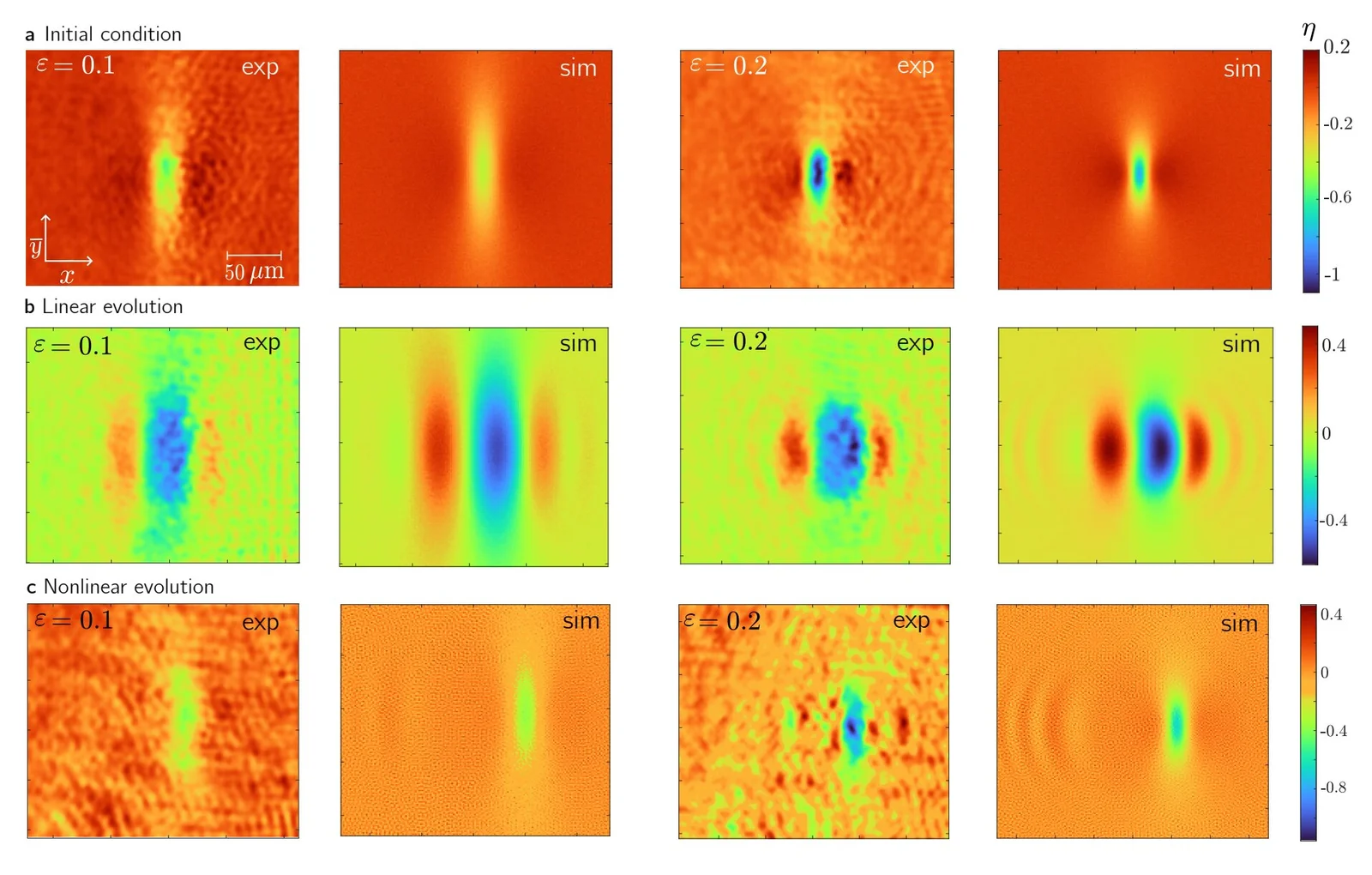

The researchers’ setup allowed them to control both the amplitude and phase of the incoming light beam with micrometric accuracy. This level of control was essential. As Dieli notes, it made it possible to prepare the lump soliton’s initial condition with high fidelity to its analytical form.

In other words, the experiment did not merely approximate the theory. It closely matched it, down to the fine details that matter for integrability.

With everything in place, the team launched the light into the crystal and watched what happened.

Watching Light Keep Its Promise

What they observed was something physicists had been waiting half a century to see.

The lump soliton propagated through the system while preserving its analytical shape. As it moved, it exhibited a characteristic shift in the two-dimensional plane perpendicular to its direction of motion, exactly as predicted by the KP equation. There was no spreading, no distortion, no loss of identity.

Even more striking was what happened next. The researchers sent another identical lump soliton traveling in the opposite direction and allowed the two wave packets to collide.

In most wave systems, such a collision would spell disaster. Shapes would deform, energy would scatter, and the original structures would be lost. But here, after the interaction, both solitons emerged unchanged. Their shapes remained intact, clear evidence of true integrability at work.

This was not a near miss or an approximation. It was a direct experimental realization of a multidimensional, integrable soliton.

Why This Changes the Landscape of Wave Physics

This achievement is not just about adding one more exotic wave to the physicist’s toolkit. It opens a door that had long been closed.

By demonstrating a lump soliton with high fidelity to its analytical form, Dieli’s team has shown that the KP equation is not merely a theoretical curiosity. It can describe real physical systems under carefully controlled conditions. This means physicists can now experimentally investigate the equation’s solutions rather than relying solely on simulations and mathematics.

“Our findings pave the way for the experimental investigation of the KPI equation and its solutions,” Dieli explains, “ensuring high fidelity to its analytical form.” According to the team, this level of precision has never before been achieved in multidimensional nonlinear wave experiments.

Why This Research Matters

At its heart, this work answers a fundamental question about nature. Can the delicate balance described by integrable mathematics survive in the messy, imperfect world of real materials and real experiments? The answer, now, is yes.

By creating the first experimental lump soliton, physicists have shown that stability, resilience, and order can exist even in complex, multidimensional systems. This result strengthens the bridge between mathematical theory and physical reality, offering a new way to test ideas that were once purely abstract.

Beyond the specific achievement, the experiment demonstrates the power of precise control over light and matter. It shows that with the right tools and understanding, physicists can sculpt waves that behave in extraordinary ways.

After decades of waiting, a wave that was once only imagined has finally been seen. And in holding its shape against every expectation, it reminds us that some ideas, no matter how long they wait, are worth the patience.

Study Details

Ludovica Dieli et al, Observation of lump solitons, Physical Review Letters (2025). DOI: 10.1103/ggbs-y21w