For as long as humans have learned to harness fire, one question has quietly followed every technological leap: how do you turn raw heat into something useful? From early steam engines to modern power plants, this challenge has shaped entire civilizations. Now, physicists at Trinity College Dublin believe that light itself may offer a surprising new path forward.

Their work does not arrive as a finished machine or a shining new device. Instead, it comes as a powerful idea, a theoretical insight into how photons, the tiny particles that make up light, behave when they are trapped and guided in just the right way. If their understanding proves correct in upcoming laboratory tests, it could point toward a future where more of the energy pouring down from sunlight, or glowing from lamps and LEDs, can be transformed into something far more useful.

The research has just been published in Physical Review A, marking an important step in a story that blends the strange rules of quantum physics with the timeless principles of heat engines.

When Light Stops Acting Alone

Under ordinary conditions, light is unruly. Photons zip around independently, spreading energy in all directions. This is why sunlight warms your skin rather than forming a sharp, focused beam. But physicists have learned that when photons are confined inside microscopic optical devices, their behavior can change in dramatic ways.

Trapped in a tiny space, photons can undergo a process known as condensation. Instead of acting like countless individual particles, they begin to move together, collectively. The result is a remarkable transformation: light energy gathers into a small, intense beam of a single, very pure color, closely resembling the output of a laser.

This phenomenon is not new. Experiments have already shown that photon condensation can happen. But until now, there has been a catch. Every successful demonstration relied on energy that was already highly organized and concentrated, typically provided by a laser itself. In other words, scientists needed an already refined form of energy to create another refined form of energy. That limitation has kept the phenomenon largely confined to laboratories.

The new work from Trinity College Dublin suggests something far more intriguing may be possible.

Turning Messy Light into Order

The theoretical breakthrough centers on a bold idea: photon condensation does not have to depend on carefully prepared laser input. According to the researchers’ analysis, it may also occur when the incoming energy is diffuse, spread out and disorganized, just like the light we encounter every day from the Sun, household lamps, or LED bulbs.

This shift is profound. Diffuse light is everywhere, but it is notoriously difficult to use efficiently. Much of it simply becomes heat and dissipates. If such light could be coaxed into condensing, it would effectively turn a chaotic energy source into a focused, laser-like output.

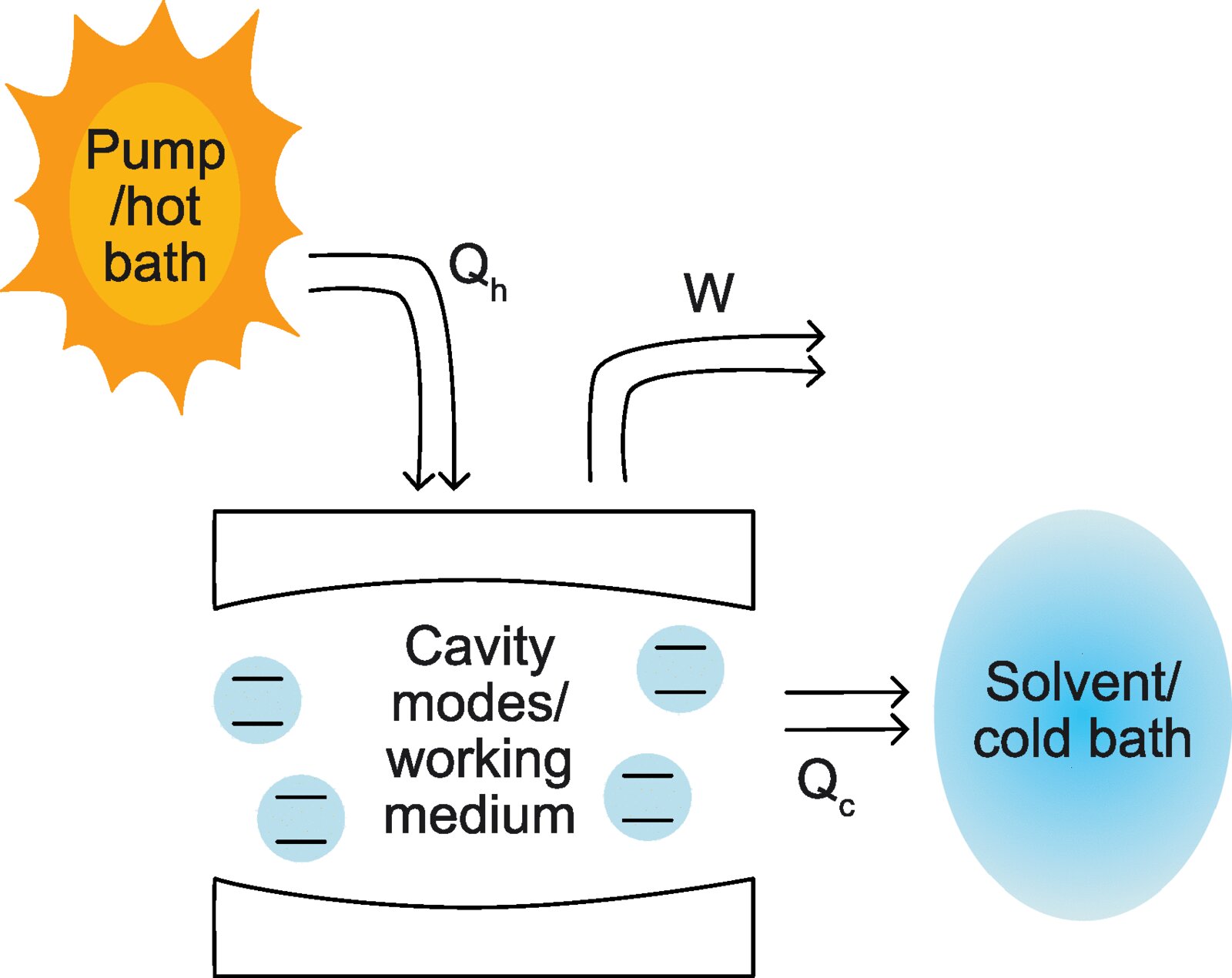

Paul Eastham, Naughton Associate Professor at the School of Physics at Trinity and senior author of the study, explains that the key lies in how these tiny optical devices behave. By modeling systems that trap light in extremely small regions of space, the team discovered that photon condensation follows the same underlying principles that govern heat engines.

Heat engines are machines designed to do something deceptively simple: convert disorganized energy, known in physics as heat, into organized energy, called work. Steam engines, power plants, and countless other technologies all obey the same fundamental laws that limit how efficient this conversion can be.

Remarkably, those very laws also appear to determine whether photons will condense.

The Laws That Bind Steam and Light

At first glance, steam engines and trapped photons seem worlds apart. One involves boiling water and pistons, the other deals with quantum particles of light. Yet the Trinity researchers found that both are governed by the same universal constraints.

In their theoretical framework, the trapped photons effectively form a miniature heat engine. The incoming light acts as a source of heat, while the surrounding environment provides a way for excess energy to be released. Under the right conditions, some of that energy emerges not as random warmth, but as coherent emission, a laser-like beam that represents useful work.

This insight ties photon condensation directly to the grand tradition of thermodynamics. The same rules that place limits on power plants also decide whether light energy can be channeled into a condensed, usable form.

Beyond its conceptual elegance, this connection opens a door. If light-based systems can be designed with these principles in mind, they may one day become tools for guiding energy at the quantum level, turning scattered photons into something purposeful.

From Theory to the Test Bench

For now, the work remains theoretical. The researchers are clear that the next crucial step is to test their predictions in the laboratory. Only then will it be possible to see whether diffuse light sources can truly drive photon condensation in real devices.

Luísa Toledo Tude, from Trinity’s School of Physics and the first author of the study, emphasizes both the promise and the caution required at this stage. The ultimate goal of such optical devices would be to produce energy in a form that is genuinely useful. In this case, that means laser-like light, which is relatively easy to convert into other forms of energy.

Because laser-like output is already highly organized, it can be more readily adapted to perform tasks, whether that involves generating electricity or powering tiny systems. One possible future application, suggested carefully and without overstatement, could involve combining these devices with solar cells. If successful, such a pairing might increase the amount of electrical energy captured from sunlight.

Still, the researchers stress that it is too early to make strong claims. The laboratory tests will determine how far this idea can go beyond equations and models.

Light as a Working Engine

What makes this research especially striking is how it reframes our understanding of light. Rather than seeing photons merely as carriers of illumination or warmth, the study invites us to think of them as participants in a working engine.

In this picture, light flows through a carefully designed system, shedding excess energy and emerging transformed. The output is not just brightness, but order. Not just heat, but work.

This way of thinking bridges the gap between classical machines and quantum systems. It suggests that even at microscopic scales, energy can be guided and shaped by the same principles that have governed engines for centuries.

Such a perspective could influence the development of future optical devices, especially those designed to manage energy with extreme precision. From systems that harvest light more effectively to tiny engines powered directly by radiation, the theoretical groundwork is now being laid.

Why This Research Matters

At its heart, this work addresses one of science’s most enduring challenges: how to turn abundant, disorganized energy into something we can actually use. Sunlight floods our planet every day, yet much of it remains beyond our full control. Lamps and LEDs surround us, but their energy often dissipates as waste heat.

By suggesting a way to concentrate diffuse light into a usable, laser-like form, this research points toward a future where more of that energy can be captured and repurposed. It does not promise instant solutions or revolutionary devices tomorrow. Instead, it offers a carefully reasoned path forward, grounded in well-established physical laws.

If experiments confirm the theory, the implications could ripple across fields that depend on light, from energy harvesting to microscopic machines. Even more importantly, the study shows that the ancient laws governing heat and work still have new stories to tell, even when applied to the smallest particles of light.

In that sense, the research is not just about photons or engines. It is about finding order in chaos, and learning, once again, how nature’s deepest rules can help us do more with the energy already all around us.

Study Details

Luísa Toledo Tude et al, Photon condensation from thermal sources and the limits of heat engines, Physical Review A (2026). DOI: 10.1103/6lyv-trfj