Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma (FLC) is an exceptionally rare form of liver cancer, mounting an unexpected and intense attack on children, adolescents, and young adults. Unlike many cancers that present with predictable symptoms, FLC often flies under the radar, with signs that can vary considerably between individuals. This variability complicates its early detection, and by the time it’s accurately diagnosed, the cancer has often metastasized, making it much harder to treat. Furthermore, standard drug treatments for common liver cancers, which typically target other molecular pathways, not only fail to benefit FLC patients but can actually worsen their condition.

However, hope is on the horizon thanks to breakthrough research. A team from Rockefeller University’s Laboratory of Cellular Biophysics, under the leadership of Sanford M. Simon, has uncovered critical new insights into the molecular foundations of FLC. Their work, which includes the discovery of a distinct molecular “signature” specific to FLC tumors, could revolutionize the way this devastating disease is diagnosed, treated, and understood. This signature identifies a set of activated genes that makes FLC biologically unique among liver cancers, laying the groundwork for more effective treatments and improved survival rates.

The Journey to Understanding FLC: Ten Years of Discovery

Albert Einstein’s famous quote about the value of curiosity and persistence in research is fitting for the journey to understand FLC. In the early 2010s, Simon’s team, motivated by both scientific rigor and personal circumstances—Simon’s own teenage daughter, Elana, had been diagnosed with FLC—began investigating the origins of the disease. In 2014, their pioneering research led to the discovery that FLC results from a gene fusion between DNAJB1 and PRKACA due to a small deletion in chromosome 19.

While at first this discovery was groundbreaking, it led Simon’s lab to an even more compelling insight: it wasn’t the fusion itself that drove the disease, but rather the resultant overproduction of PRKACA. This gene encodes the catalytic subunit of Protein Kinase A (PKA), a protein that plays a crucial role in regulating cellular activities. Normally, PKA activity is balanced by an inhibitory subunit, but in FLC cells, this balance is lost—too much PKA activity is unleashed, disrupting the normal function of the cell and ultimately promoting the growth of cancerous cells.

Uncovering the Disease’s Molecular Signature

For their latest study, Simon and his team sought to deepen their understanding by identifying the “fingerprint” of FLC. Researchers wanted to know if there was a common molecular pathway that followed the burst of PKA activity in FLC cells. Moreover, since there are other liver tumors that exhibit FLC-like characteristics but lack the DNAJB1::PRKACA fusion, the team wanted to understand how FLC differed from these other cancer types.

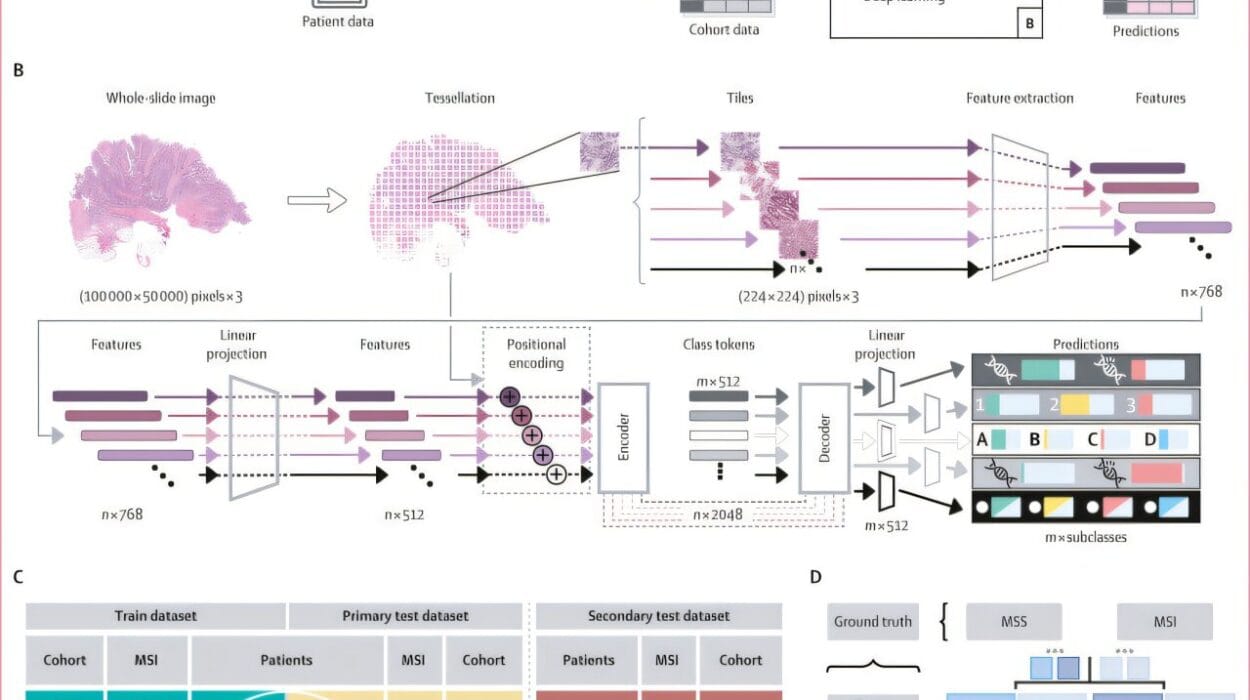

To unravel these questions, the team launched the largest analysis of its kind. They examined 1,412 liver tumor samples from a variety of cancers, including 220 from FLC patients. This data came from multiomics sequencing, which involves an integration of various kinds of data, such as genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic information, to offer a comprehensive understanding of tumor biology. The dataset included the largest number of FLC samples ever included in a single analysis, which allowed the team to identify critical patterns not just across different cancers, but within the FLC tumors specifically.

Their findings revealed that FLC exhibits a distinct transcriptomic signature. The researchers identified 301 genes that were expressed differently in FLC than in other liver cancers. Thirty-five of these genes showed especially high expression in FLC and had never been linked to liver cancer before. This discovery could have significant diagnostic value, as these genes could be used as biomarkers to accurately identify FLC in patients, particularly in its early stages.

In addition to helping differentiate FLC from other liver tumors, the researchers identified a key feature of FLC tumors: all tumors with increased amounts of the catalytic subunit of PKA, regardless of the type of fusion or the tissue origin, exhibited similar molecular changes. For example, patients with a PRKACA fusion in cells from the pancreas or bile ducts also displayed the same transcriptomic changes seen in FLC, suggesting that diseases driven by these fusions in non-hepatic tissues are molecularly connected to FLC. This finding is crucial because it suggests that FLC and related diseases share a common biochemical pathway, one that can potentially be targeted therapeutically.

Beyond the Fusion: PKA Imbalance as the Root Cause

The research revealed a startling conclusion: FLC should not necessarily be defined by the genetic fusion event (DNAJB1::PRKACA) itself, but by the imbalance in protein activity that results from it. When there is an excessive amount of the catalytic subunit of PKA relative to its regulatory counterpart, the cells lose control over critical pathways, which contributes to tumor growth. This revelation significantly reframes our understanding of what causes FLC, suggesting that therapies aiming to correct the imbalance of PKA could offer new hope for patients.

The researchers’ efforts went a step further by investigating tumor margins in FLC patients. A surprising discovery emerged when the margins of some tumors contained cells exhibiting the same distinct molecular signature of FLC, even though they hadn’t been captured in the initial resection of the tumor. These remnants of cancerous cells posed a potential time bomb, as they could lead to the regrowth of the tumor. This finding underscores the importance of thoroughly examining tumor margins during surgery and could prompt better practices in removing all cancerous cells to reduce the chances of recurrence.

The Promise of a New Treatment: Clinical Trials of Targeted Drugs

While the findings about FLC’s molecular signature open doors to better diagnosis, there is an equally important component: the potential to treat FLC more effectively. In light of these new insights, Simon’s lab has launched a promising clinical trial to test a combination of two drugs—DT2216 and irinotecan—that showed early promise in preclinical studies. Earlier research indicated that when used together, these drugs might target FLC more effectively than current treatments.

This clinical trial is supported by significant research networks such as the Children’s Oncology Group and the Pediatric Early Phase Clinical Trials Network (PEP-CTN) of the National Institutes of Health. If successful, the drugs could represent a breakthrough in FLC treatment, particularly for patients who have so far been excluded from effective therapies due to the distinct molecular nature of their cancer.

In addition to this trial, the Simon Lab is part of an exciting global initiative: the Cancer Grand Challenge. This effort, which involves collaboration between multiple research labs, focuses on degrading oncoproteins like the PRKACA fusion protein in FLC to prevent or eliminate tumors. Simon’s lab is leading efforts on developing targeted therapies that attack these cancer-driving proteins, with the hope that these insights will apply to FLC and related cancers, potentially offering new treatment options for rare diseases worldwide.

Simon himself reflects on the journey: “A decade ago, our goal was to make rapid progress in understanding a rare disease, so that our findings could serve as a road map not just for FLC, but for other cancers too. We are beginning to see the fruits of that labor.” His team’s discoveries offer hope for not only improving outcomes for FLC patients but for broader applications in treating other cancers like Ewing sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and neuroblastoma.

Conclusion

As Simon’s decade-long research continues to unfold, it becomes increasingly clear that the molecular insights gained about FLC are much more than a step toward treating a rare disease. They are creating a ripple effect that could inspire new therapies and diagnostic tools for numerous types of cancer. By unlocking the mechanisms that drive FLC, Simon and his team not only make a hopeful difference for children, adolescents, and young adults afflicted by this rare liver cancer, but also point the way forward for understanding and treating other cancers where protein imbalances are at the root. Ultimately, these advances could contribute to more personalized, more effective cancer therapies that could save lives, even in cases where the diagnosis once seemed almost impossible to make.

Reference: David Requena et al, Liver cancer multiomics reveals diverse protein kinase A disruptions convergently produce fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-55238-2