Nearly a decade has passed since the Zika virus epidemic shook Brazil and alarmed the world. The virus, carried mainly by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, left behind devastating consequences, particularly for pregnant women and their babies. Images of newborns affected by microcephaly—an abnormal smallness of the head caused by impaired brain development—became emblematic of the epidemic’s cruelty.

Though the outbreak eventually receded, Zika never truly disappeared. The virus remains a public health threat, especially in tropical regions where mosquitoes thrive. For years, researchers have been racing against time to develop a vaccine that can both protect against infection and prevent the severe consequences it brings.

Now, a team at the Institute of Tropical Medicine of the University of São Paulo’s Medical School (IMT-FM-USP) has made a breakthrough. Their newly developed vaccine has shown remarkable success in preclinical tests with mice, offering not just protection against the virus, but also shielding the animals from brain and testicular damage—two of the most concerning complications of Zika.

Building a Safer Vaccine

At the heart of this achievement is a technology known as “virus-like particles” (VLPs). Unlike traditional vaccines, which rely on weakened or inactivated versions of the virus, VLP-based vaccines are safer. They don’t contain the pathogen’s genetic material. Instead, they mimic the virus’s outer shell, tricking the immune system into mounting a defense without the risk of causing disease.

Dr. Gustavo Cabral de Miranda, one of the lead researchers, explains it this way: “We designed a formulation that can neutralize the pathogen and protect rodents from both brain inflammation and testicular damage. This approach makes the vaccine much safer and more economical to produce, without needing additional substances to enhance the immune response.”

The vaccine uses a well-established VLP platform called QβVLP. To this structure, the scientists attached a crucial part of the Zika virus envelope known as EDIII—an antigen that helps the virus connect to human cells. By presenting EDIII on the surface of the VLP, the vaccine essentially trains the immune system to recognize and block the virus before it can invade.

Protecting the Brain and Reproductive Health

The most remarkable part of the study is not just that the vaccine produced a strong immune response, but that it also protected the animals from organ damage caused by the virus. Zika’s effects on the brain are well known, especially in the context of fetal development. But in laboratory studies, the virus has also been shown to damage the testicles, potentially impairing fertility.

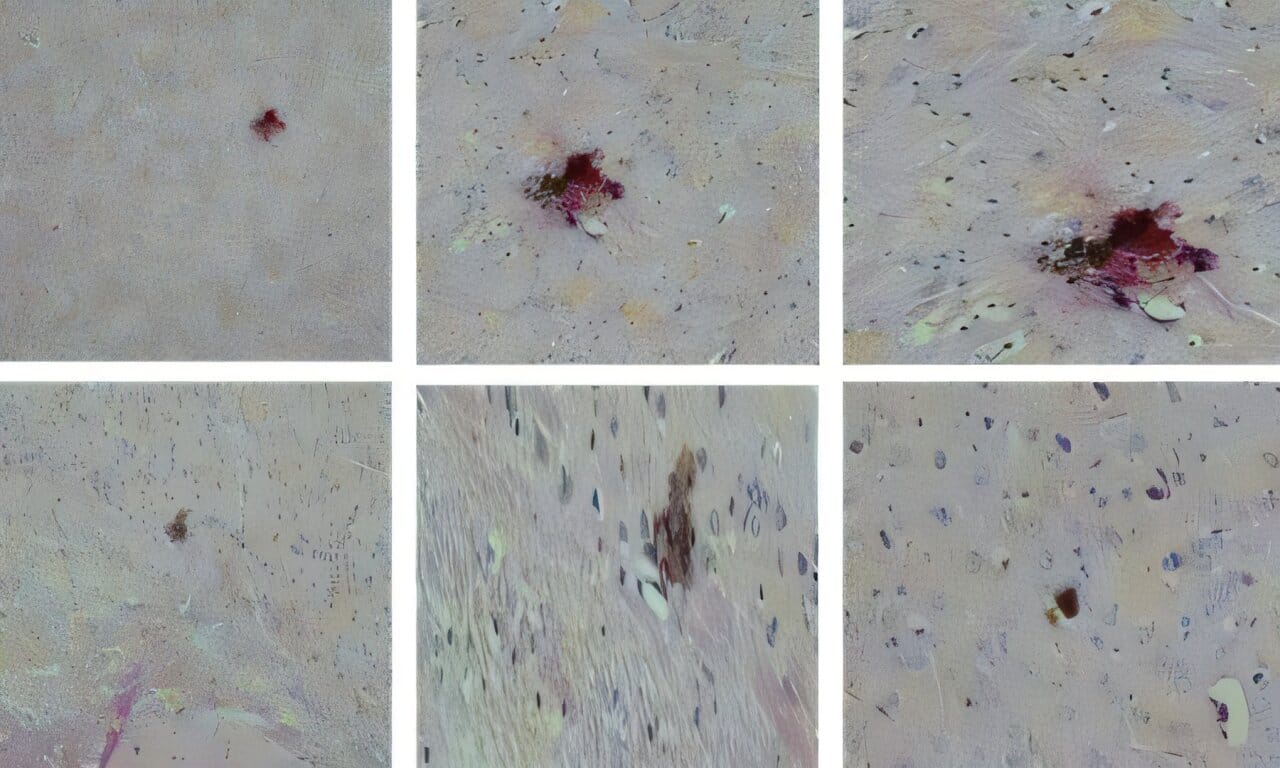

Tests on genetically modified mice—engineered to be more vulnerable to Zika—showed that the vaccine triggered both antibody production and T cell activity. These immune defenses were powerful enough to stop the virus from spreading and causing harm.

“The vaccine demonstrated the ability to protect male mice against testicular damage,” explains Nelson Côrtes, the study’s first author. “This is crucial because Zika is not only mosquito-borne, it can also be sexually transmitted. Protecting reproductive health is therefore an important aspect of prevention.”

The researchers examined multiple organs, including the brain, kidneys, liver, ovaries, and testicles, and found that the vaccinated mice were safeguarded from inflammation and cellular damage. This dual protection—against infection and its long-term consequences—marks a significant advance in vaccine development.

Solving the Dengue Puzzle

One of the greatest challenges in designing a Zika vaccine has been its close relationship with dengue. The two viruses are members of the same family, and their similarities confuse the immune system. Sometimes, antibodies created in response to one virus mistakenly recognize the other, but without being strong enough to neutralize it. This phenomenon, called “antibody-dependent enhancement,” can actually make a second infection worse.

This concern has haunted vaccine developers, raising fears that a Zika vaccine could inadvertently increase the risk of severe dengue.

But the IMT-FM-USP team found a solution. By using the EDIII antigen, they ensured that the antibodies produced are highly specific to Zika. “The vaccine doesn’t cause a cross-reaction,” says Dr. Miranda. “This is very positive because it means the immune response is focused and avoids the boomerang effect seen with dengue.”

What Comes Next

The results, published in npj Vaccines, are an exciting milestone—but they are still early. So far, the vaccine has only been tested in mice. Before it can be used in humans, it will need to go through further preclinical studies, followed by carefully designed clinical trials to confirm its safety and effectiveness in people.

Nevertheless, the findings offer hope. For regions like Brazil, where mosquito-borne diseases continue to place immense pressure on healthcare systems, a safe and effective Zika vaccine could be transformative. It could protect pregnant women from the devastating consequences of infection, reduce the risk of sexual transmission, and finally close one of the darkest chapters of recent public health crises.

A Future Free of Fear

The Zika epidemic revealed the vulnerabilities of a world unprepared for emerging diseases. It showed how a virus could spread rapidly, cross borders, and leave lasting scars on families and communities. For scientists, it was also a call to action—a reminder that prevention is always better than reaction.

Now, thanks to the ingenuity of Brazilian researchers, a path toward prevention is becoming clearer. Their work demonstrates not only scientific innovation but also resilience—the determination to turn the painful lessons of the past into a safer future.

As Dr. Miranda reflects, “It’s been ten years since the Zika epidemic began, and the disease continues to be a threat. With this vaccine, we hope to give society the protection it needs, so that no family has to endure the tragedies we witnessed.”

The journey is not over, but a new chapter has begun—one in which science brings hope of a future free from the fear of Zika.

More information: Nelson Côrtes et al, A VLPs based vaccine protects against Zika virus infection and prevents cerebral and testicular damage, npj Vaccines (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41541-025-01163-4