On a brisk autumn morning in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, there is no siren announcing the arrival of influenza. No breaking news flash. Just a creeping shadow—coughs in classrooms, fevers behind closed doors, grandparents too tired to get out of bed. But somewhere in the intricate web of human connection—in workplaces, schools, and grocery store aisles—a quiet defense is taking shape. It’s not dramatic, but it’s powerful. It’s a flu shot.

At the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, a team of scientists has spent years simulating what most of us live without thinking: how viruses move among us, how they find new hosts, and how something as routine as a seasonal vaccination can transform an entire community’s health. Their findings, published in JAMA Network Open, illuminate not just data points but the invisible protection our choices offer others.

Their simulations reveal this: when we vaccinate against the flu, we’re not only protecting ourselves. We’re building walls of defense around strangers, around newborns too young for vaccines, around neighbors with compromised immune systems. We are, quite literally, shielding others with our decisions.

A Digital City That Breathes, Coughs, and Heals

The study, titled Estimated Burden of Influenza and Direct and Indirect Benefits of Influenza Vaccination, didn’t involve human volunteers in the traditional sense. Instead, it used a remarkable tool—an agent-based simulation platform called FRED, the Framework for Reconstructing Epidemiologic Dynamics. Within this virtual environment, 1.2 million digital “agents” were constructed, each mirroring the demographics and behaviors of real people living in 2010 Allegheny County.

These weren’t generic bots. Each agent had a home, a school or workplace, a daily routine. They interacted just as real people do—in buses, classrooms, and workplaces. And, like us, some got vaccinated. Others didn’t.

As the digital calendar flipped from August 2022 to May 2023, the flu began to spread among them. But what the researchers observed wasn’t chaos. It was a layered, strategic battle between virus and immunity. Vaccines didn’t just protect individuals—they redirected the entire course of the epidemic.

The Dance Between Virus and Vaccine

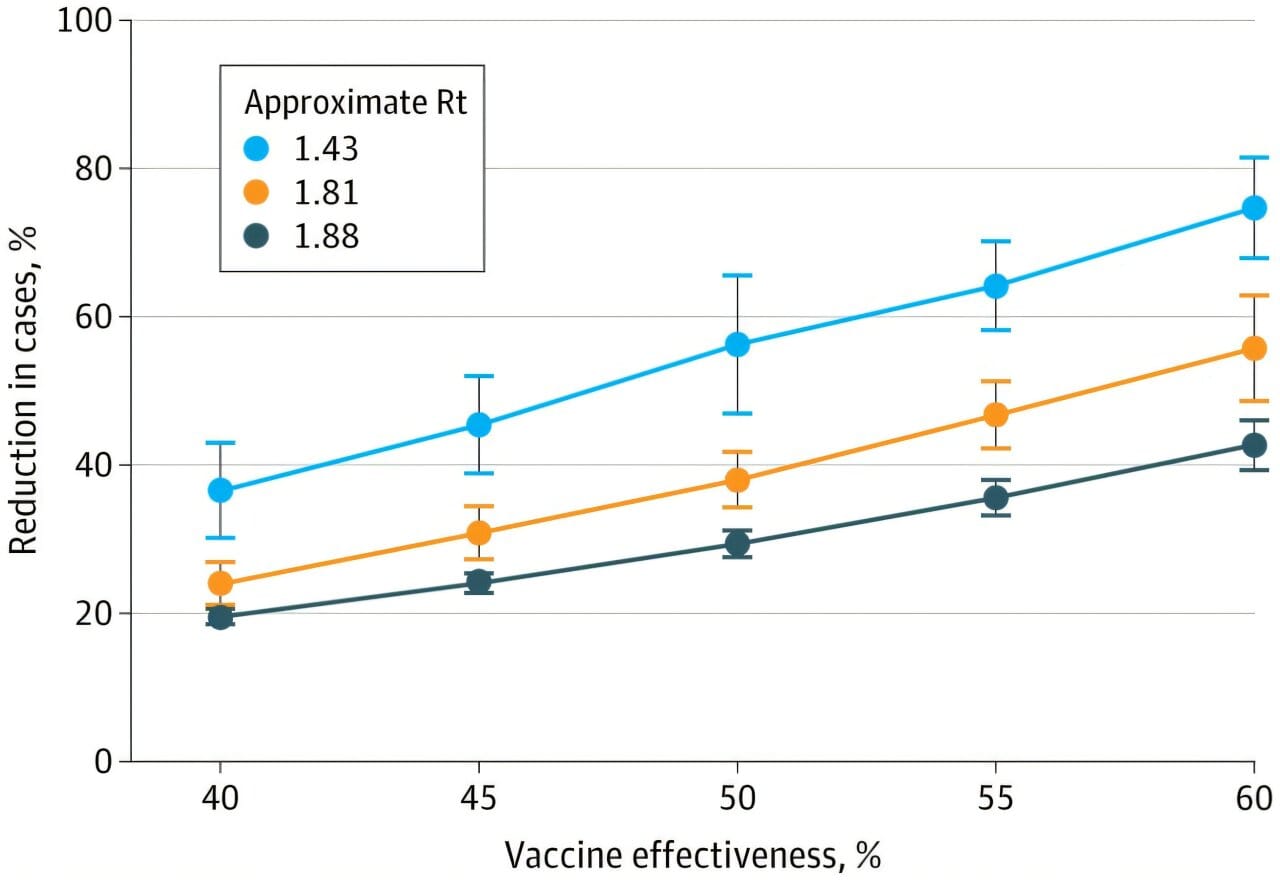

To understand the flu’s spread, scientists used a key metric known as the effective reproductive number, or Rt. This value reflects how many people, on average, one infected individual will pass the virus to. A low Rt (like 1.33) signals slow transmission. A high Rt (such as 5.0) indicates explosive spread—reminiscent of pandemic conditions like the 2009 H1N1 outbreak or even COVID-19.

In moderate transmission scenarios (Rt around 1.88), flu vaccination reduced total infections by an average of 32.9%. In less aggressive seasons (Rt closer to 1.43), the protection grew even stronger—up to 41.5%. With higher vaccine effectiveness and favorable conditions, reductions in flu cases soared to a staggering 70.3%.

These aren’t abstract numbers. Behind each digit is a real person not getting sick. A child attending school uninterrupted. A parent not needing a hospital bed. A grandparent spared a life-threatening complication.

The Quiet Heroism of Herd Immunity

One of the study’s most remarkable findings was the power of indirect protection—what scientists call “herd immunity.” In vaccinated communities, even unvaccinated individuals were less likely to fall ill simply because the virus had fewer places to go. Fewer hosts meant fewer chains of transmission. In a real sense, vaccinated individuals were creating invisible shields around those who couldn’t be vaccinated: infants under six months old, people with severe allergies, or those with fragile immune systems.

But there was a limit to this shared immunity. As Rt rose—indicating more rapid transmission—herd immunity began to fray. When Rt passed 3.92, indirect protection effectively disappeared. In such high-transmission environments, only those who had been vaccinated retained a strong defense. Their rates of infection were still significantly lower—52.6% to 61.0% fewer infections than among the unvaccinated—but the safety net no longer extended to everyone.

The message was clear: the higher the storm, the fewer shelters remain for those without armor.

Vaccination: A Community Pact, Not Just a Personal Choice

While the flu vaccine may never be perfect, it remains our best tool against a virus that kills thousands every year. Between 2010 and 2024, annual symptomatic flu cases in the United States have ranged from 9 million to over 40 million. Some years, the virus is stealthy. Others, it roars.

Yet one truth remains constant—vaccination doesn’t just reduce your own chance of getting sick. It lowers the probability that someone else, someone more vulnerable, will even encounter the virus.

In the simulations, even when only 51% of agents were vaccinated—reflecting real-world uptake rates—community-wide reductions were impressive. The direct benefit to vaccinated individuals consistently exceeded indirect benefits, but both effects combined to shift the trajectory of the epidemic in profound ways.

The ratio of infections in unvaccinated versus vaccinated people, known as the attack-rate ratio, ranged from 1.43 to 1.73. These numbers translate to a simple truth: vaccination substantially reduces your risk, and when enough people participate, it rewires the entire landscape of disease spread.

What the Simulations Teach Us About the Real World

While computer models are not crystal balls, they are powerful mirrors. The FRED platform has been used in past research to simulate measles, COVID-19, and even opioid abuse patterns. Its strength lies in its ability to capture complex social interactions and disease dynamics in human-like environments.

In this flu vaccination study, it allowed researchers to test dozens of scenarios—tweaking vaccine uptake rates, effectiveness levels, and transmission speeds to see how the epidemic would respond. What they found held true across nearly all conditions: even modest increases in vaccine coverage delivered meaningful reductions in disease burden.

This matters especially in a world where vaccine skepticism and logistical barriers prevent full population coverage. Knowing that a well-vaccinated majority can still create protective ripples offers both a scientific rationale and a moral imperative to expand access and education.

When Numbers Become Lives

Behind every model are real people. The mother with asthma, terrified every winter of what the flu might do. The nurse working through flu season, unable to miss a day. The newborn whose immune system is too fragile to withstand even a routine virus. For them, your flu shot is a gift they will never see—but one that might save their lives.

The University of Pittsburgh researchers didn’t just crunch data. They built a digital mirror of society. And in it, they showed that public health is not simply about avoiding illness; it’s about how we choose to care for one another, even in invisible ways.

The Takeaway in an Uncertain Season

As we brace for another flu season, the questions echo: Will it be mild or severe? Will the vaccine match the circulating strain? Will people get vaccinated in time?

While the answers vary year to year, the foundation remains solid. Vaccination, even if imperfect, dramatically reduces the chance of infection and reshapes the contours of community risk. It protects not just the person receiving it, but those standing unknowingly in their orbit.

In a world filled with uncertainty, the flu vaccine is a small certainty. A shot in the arm. A ripple through society. A decision that may never make headlines but has the power to rewrite someone else’s story.

And in that quiet choice, science and humanity meet.

Reference: Mary G. Krauland et al, Estimated Burden of Influenza and Direct and Indirect Benefits of Influenza Vaccination, JAMA Network Open (2025). DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2025.21324