Every year, more than 300,000 people in the United States hear three words that change their lives forever: “You have cancer.” For many women, those words signal the beginning of an exhausting, emotional, and uncertain journey with breast cancer — a disease that touches nearly every family in some way. According to the American Cancer Society, breast cancer remains the second leading cause of cancer-related death among women.

But recently, something even more troubling has emerged. Scientists are finding evidence that the danger may not only lie in our genes or lifestyles — it may also be in the very ground beneath our feet and the air we breathe.

In Florida, researchers at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine have uncovered a potential link between breast cancer and environmental pollution from Superfund sites — areas contaminated by hazardous waste and designated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for cleanup. These findings are not just statistics; they are stories of real people living near toxic sites, wondering whether their environment is silently poisoning them.

The Hidden Toxic Neighbors

Florida is home to 52 active Superfund sites — a chilling number when you realize that each represents a place where toxic chemicals have seeped into the soil, groundwater, or air. These sites are remnants of old industrial facilities, landfills, or factories, many abandoned but still dangerous.

Dr. Erin Kobetz, an epidemiologist and associate director for community outreach at Sylvester, recalls how this investigation began — not in a laboratory, but in conversation.

“Members of our community raised concerns that where they lived was making people sick,” she said. “Overwhelmingly, the people who were speaking up lived in neighborhoods relatively close to a Superfund site.”

Their fears were not unfounded. When Dr. Kobetz and her team began analyzing cancer data from across Florida, they noticed a disturbing pattern: people living closer to these polluted areas seemed to have higher rates of advanced breast cancer.

The First Alarming Discovery

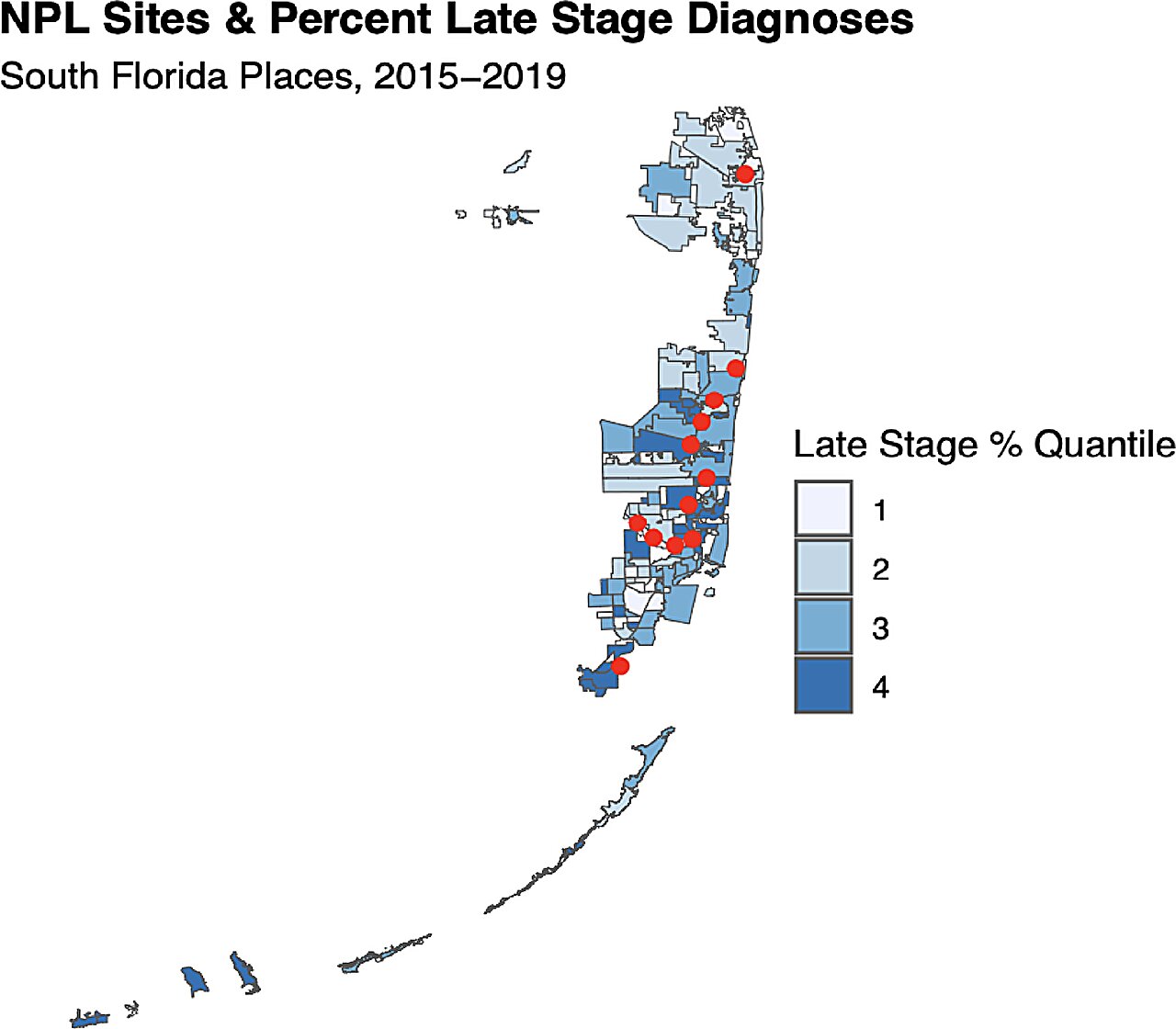

In their first major study, Kobetz and her team analyzed more than 21,000 cases of breast cancer diagnosed in Florida between 2015 and 2019. Using Sylvester’s advanced data portal, SCAN360, they could examine health risks at a neighborhood level — almost house by house.

Their findings were startling. Women who lived in the same census tract as at least one Superfund site were 30% more likely to have metastatic breast cancer — cancer that had already spread beyond the breast at the time of diagnosis.

Metastasis is what makes cancer deadly. It’s the point at which the disease becomes harder to treat and survival rates drop sharply. That a woman’s ZIP code could play a role in this was both shocking and heartbreaking.

The Rise of a Ruthless Enemy: Triple-Negative Breast Cancer

The team didn’t stop there. They turned their attention to one of the most aggressive and deadly forms of the disease: triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Unlike other types, TNBC doesn’t respond to hormonal therapies or targeted drugs. It grows quickly, spreads rapidly, and often affects younger women and women of color.

When researchers compared TNBC cases to environmental data, the results again pointed to a chilling pattern. Living near a Superfund site was linked to a higher risk of developing this aggressive subtype of breast cancer.

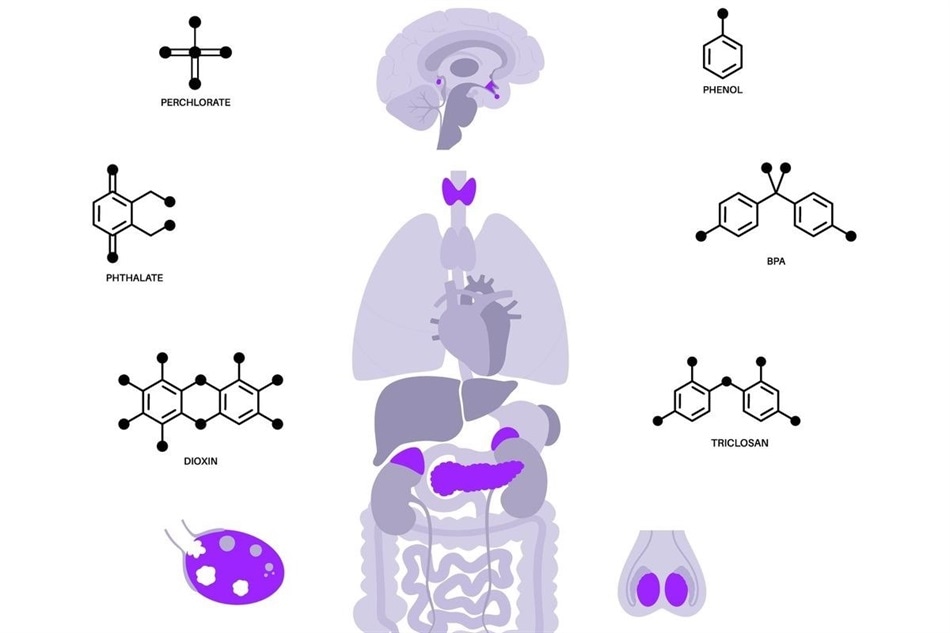

But the story didn’t end there. The researchers found another environmental villain: particulate matter 2.5 (PM2.5) — microscopic air pollutants smaller than the width of a human hair. These particles come from car exhaust, industrial emissions, and even burning waste. In South Florida, exposure to higher levels of PM2.5 was linked to an increased risk of TNBC.

Both studies, published in Scientific Reports and Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, revealed what many residents had long suspected — that the environment around them could be fueling one of the deadliest diseases of our time.

The Science Beneath the Surface

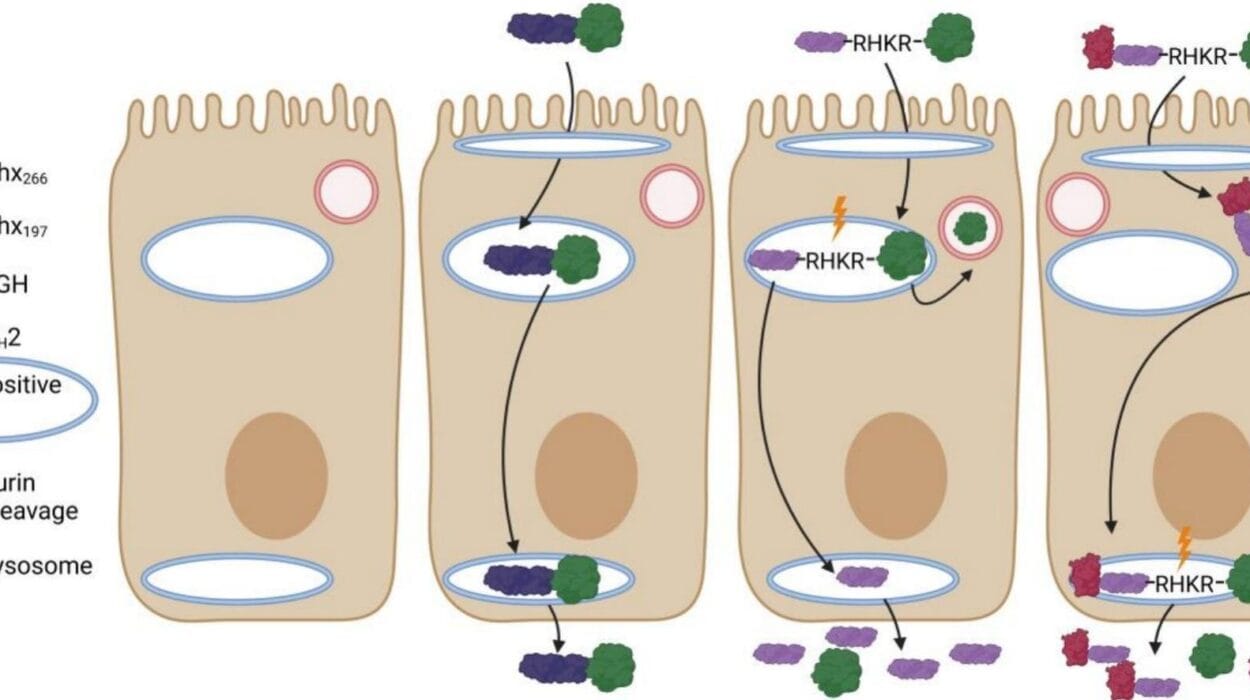

Understanding that pollution might influence cancer risk is only the beginning. The next challenge was to uncover how toxic environments could be shaping disease at the molecular level — inside the cells and DNA of patients themselves.

That’s where Dr. Aristeidis Telonis, a research assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the Miller School, stepped in. He wanted to know if there were chemical fingerprints — biological clues — left behind by environmental stress and social disadvantage.

The research team analyzed tumor samples from 80 breast cancer patients in the Miami area. They didn’t just look at genes; they examined the epigenome (chemical markers that turn genes on or off) and the RNA, which acts like real-time messages showing how DNA is being expressed.

What they found was both fascinating and sobering. Patients from neighborhoods with fewer health-promoting resources — such as limited access to healthcare, green spaces, and clean environments — were more likely to show distinct molecular signatures associated with aggressive breast cancer.

Telonis described this as a “deprivation index” — a measurable link between social adversity, environmental stress, and the biology of disease. “This deprivation index is very strongly associated with more aggressive breast cancers,” he said. “It’s a simple, but very important correlation.”

The research, published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, marks one of the first attempts to connect environmental and social conditions to molecular changes inside tumors. It opens a path toward more personalized care — where a patient’s neighborhood and life circumstances might one day help doctors predict and treat cancer more effectively.

When Data Meets Humanity

Behind every dataset, every statistic, every biomarker is a person — a mother, daughter, sister, or friend — fighting for her life. The Sylvester team’s research is more than a scientific pursuit; it’s an act of listening to communities that have too often gone unheard.

“We have a signal,” Dr. Kobetz said, “and we’re compelled and encouraged by our Community Advisory Committee to pursue it. The community had a perspective, and now we have empirical and scientific data to suggest their concerns may be valid.”

It’s a model of science rooted in compassion — where research doesn’t just happen in sterile labs but begins with conversations in neighborhoods, churches, and community centers.

The Larger Picture: Environment, Inequality, and Health

These studies reveal a painful truth: cancer is not just a biological disease; it is also a social one. Where a person lives, their access to healthcare, their exposure to pollution, and even their level of economic opportunity can profoundly shape their health outcomes.

For too long, discussions about cancer risk have focused narrowly on genetics and personal choices. But biology does not exist in a vacuum. The body is constantly interacting with the environment, absorbing the world through every breath, meal, and drop of water.

When the air is poisoned, the soil contaminated, and the neighborhoods neglected, the result can be devastating. The findings from Florida serve as a reminder that addressing cancer requires more than medicine — it demands justice.

Toward a Healthier Future

The work being done at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center is only the beginning. Scientists now have evidence to further explore how pollution, poverty, and stress intertwine to shape the biology of disease. With more research, these insights could transform how we prevent, diagnose, and treat breast cancer.

Dr. Telonis hopes that one day doctors will look not just at a tumor under a microscope, but at the world surrounding the patient. “The goal is that when a patient comes in, the doctor not only assesses the tumor characteristics, but also considers the patient’s resources and what that may mean molecularly,” he said. “Eventually, that should help inform treatment.”

Meanwhile, communities across Florida — and the nation — are speaking up, demanding cleaner environments and stronger protections against pollutants that may be endangering their health.

Hope in Action

Every discovery, every new piece of evidence, is a step toward hope. The link between Superfund sites and breast cancer may be deeply unsettling, but it also opens a new path — one where science, policy, and community unite for change.

Breast cancer may still be one of humanity’s fiercest enemies, but understanding its roots — in our biology, our environment, and our society — brings us closer to defeating it.

For the women living near these contaminated sites, for the families who’ve lost loved ones too soon, and for the generations yet to come, this research carries a message: your health matters, your story matters, and your environment should never be a silent accomplice in disease.

The fight against breast cancer is not just fought in hospitals. It’s fought in neighborhoods, in policy decisions, and in every effort to ensure that where we live helps us thrive — not fall ill.

Because life, like science, begins with one powerful belief: that every person deserves a chance to live in a world that nurtures health, not harms it.

More information: Peter A. Borowsky et al, Residential proximity to national priorities list superfund sites is associated with increased likelihood of metastatic breast cancer presentation, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-05722-6

Peter A. Borowsky et al, Residential Proximity to NPL Superfund Sites and High Particulate Matter Exposure is Associated with Increased Likelihood of Triple Negative Breast Cancer, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention (2025). DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-25-0677

Aristeidis G. Telonis et al, Molecular Portraits of Social Adversity in Breast Cancer: Neighborhood Disadvantage Is Associated with Epigenetic Deregulation of Key Oncogenic Pathways, Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention (2025). DOI: 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-25-0123