It begins long before anyone notices — before a hand trembles, before a step falters, before a thought slips away into fog. Huntington’s disease is not an illness that arrives suddenly; it is a seed planted in the very blueprint of life. This seed, a mutation in a single gene, can rest quietly for decades before sprouting into a relentless cascade of symptoms that ripple through both mind and body.

For many families, Huntington’s disease is not just a diagnosis. It is a shadow that has followed generations, an unwelcome inheritance that cannot be returned. It has taken fathers before their children could graduate, mothers before they could see their grandchildren, and siblings who once ran together in childhood fields. Yet despite its devastating power, Huntington’s disease is also a puzzle — one that scientists have been painstakingly working to piece together for more than a century.

The Discovery and the Name

The earliest known descriptions of what we now call Huntington’s disease came from scattered medical reports in the 19th century. But it was George Huntington, a young American physician, who in 1872 published a clear, haunting account of the condition. His essay, “On Chorea,” captured not only the physical symptoms but also the way the illness tore through families. Huntington observed its hereditary nature, noting that when one parent carried the disease, about half of their children would eventually show symptoms.

The word chorea comes from the Greek word for “dance,” reflecting the twisting, jerking movements that the disease often causes. But the name “Huntington’s chorea” would later evolve into “Huntington’s disease,” acknowledging that it is far more than a movement disorder — it is a whole-brain disease that affects emotion, thinking, and behavior.

The Genetic Culprit

Huntington’s disease is caused by a mutation in a single gene called HTT, located on chromosome 4. This gene carries the instructions for producing a protein known as huntingtin, whose exact role in healthy cells is still being explored. In those without the disease, the HTT gene contains a section where a three-letter DNA sequence — CAG — repeats between 10 and 35 times.

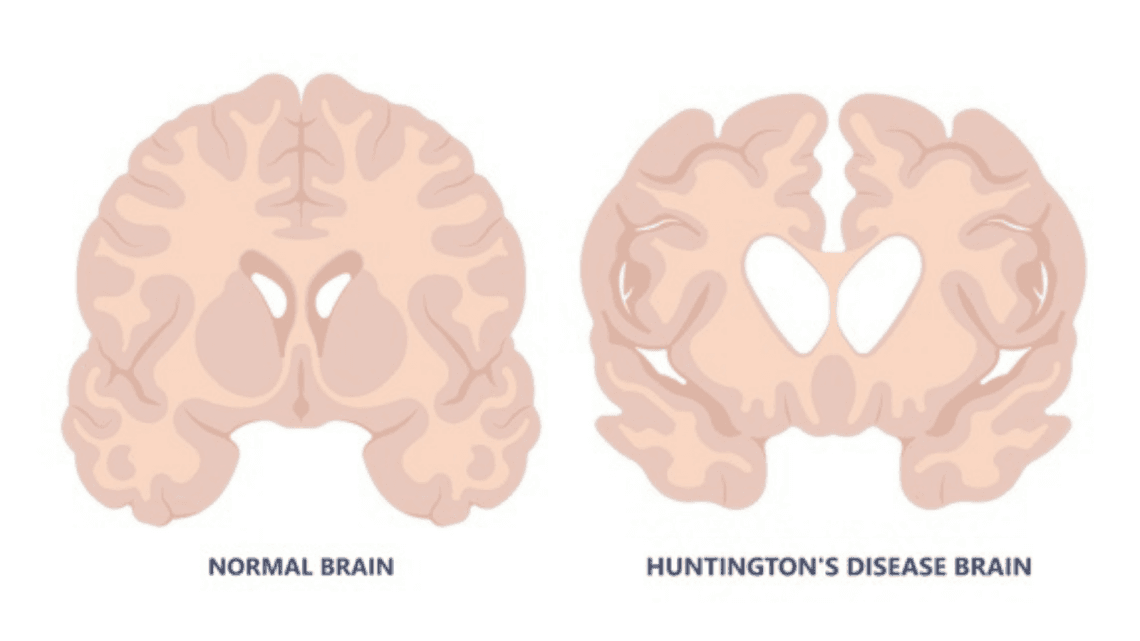

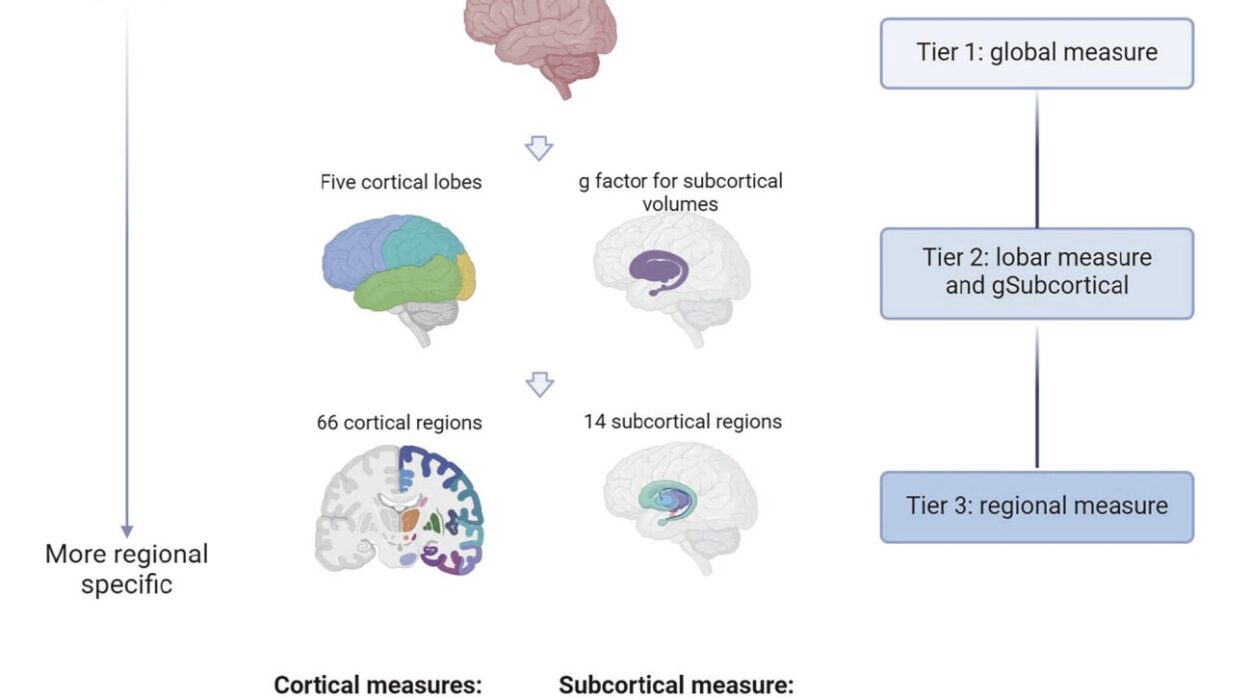

In people with Huntington’s disease, that CAG sequence is abnormally expanded, repeating 36 or more times. This expansion changes the structure of the huntingtin protein, making it toxic to nerve cells. Over time, this faulty protein builds up and damages specific areas of the brain, especially the basal ganglia, which is crucial for movement control, and the cerebral cortex, which governs thought, perception, and emotion.

The cruel nature of the mutation lies in its certainty: Huntington’s disease is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern, meaning that if a parent carries the expanded gene, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. There is no “carrier” state — if you inherit the mutation, you will eventually develop the disease unless you die of something else first.

The Long Silence Before Symptoms

One of the most insidious features of Huntington’s disease is its delayed onset. Most people begin to notice symptoms in their 30s or 40s, but the damage to the brain has been building for years, even decades.

For some, early signs are subtle: a touch of clumsiness, a mild change in mood, difficulty concentrating at work. Friends may notice a personality shift — irritability replacing patience, withdrawal replacing sociability. These changes are often mistaken for stress, midlife crises, or depression unrelated to neurological disease.

The “classic” motor symptoms — the jerky, involuntary movements called chorea — may not appear until later. By the time these movements are visible, other systems in the brain are already struggling.

The Face of the Disease

As Huntington’s disease progresses, it weaves together three strands of symptoms: motor, cognitive, and psychiatric. These strands are deeply intertwined, often making the disease feel like it attacks the entire essence of a person.

On the motor side, chorea is the hallmark. It can begin as small, restless movements — a flick of the fingers, a twitch of the lips — and evolve into large, writhing motions that make walking, eating, and speaking difficult. Over time, muscles may also become rigid, and voluntary movements can slow, creating a strange contrast of uncontrolled flailing and frustrating slowness.

Cognitive changes begin with difficulty planning, organizing, or multitasking. The person may have trouble keeping track of details or switching between tasks. This isn’t just “forgetfulness” — it’s a deep disruption of executive function, the mental control center that lets us manage our lives.

Psychiatric symptoms can range from depression and anxiety to irritability, aggression, or apathy. Sometimes, these changes are the most distressing for families, as the loved one they knew seems to fade into someone unrecognizable.

Eventually, as brain cells continue to die, communication, mobility, and independence are lost. Late-stage Huntington’s disease leaves individuals dependent on others for all aspects of care, even as they may still remain aware of their surroundings.

The Weight of an Inheritance

For families with a history of Huntington’s disease, the knowledge of its hereditary nature can be both a burden and a haunting question mark. The 50/50 chance of inheriting the mutation means that adult children of an affected parent face a lifelong decision: whether to undergo genetic testing to learn their fate.

Genetic testing for Huntington’s disease can be done long before symptoms appear, but deciding to take it is a deeply personal, often agonizing choice. Some choose to know, wanting certainty for life planning, relationships, or reproductive decisions. Others prefer not to know, living in a state of uncertainty that feels, paradoxically, less painful than a definitive answer.

The psychological toll is immense. People at risk often describe living with “a shadow over the future,” making long-term plans difficult and sometimes avoiding them altogether. Families may be split between those who know their status and those who do not, each path carrying its own emotional weight.

How the Disease is Diagnosed

Diagnosing Huntington’s disease involves a combination of clinical examination, family history, and genetic testing. A neurologist will typically look for the characteristic movement patterns, assess cognitive function, and evaluate psychiatric symptoms.

If the patient has a family history, the suspicion is stronger. But in some cases, people with no known family history are diagnosed — often because a parent was misdiagnosed with another condition, or because the mutation appeared as a rare new change in the gene.

The genetic test is definitive. By analyzing DNA from a blood sample, laboratories can count the number of CAG repeats in the HTT gene. A count of 40 or more repeats confirms the disease; 36–39 repeats may lead to the disease but with variable onset and severity. Counts below 36 are considered normal.

No Cure, But Paths to Care

There is currently no cure for Huntington’s disease — no way to reverse or halt the degeneration once it begins. Yet treatment can help manage symptoms and improve quality of life.

Medications can reduce chorea, ease depression and anxiety, and help with irritability. Physical therapy can maintain mobility for as long as possible, while speech therapy can aid communication and swallowing. Occupational therapy helps adapt homes and routines to changing abilities.

Because the disease affects the whole person — mind, body, and relationships — care often requires a multidisciplinary team: neurologists, psychiatrists, physical therapists, social workers, and genetic counselors. Support groups can be lifelines for both patients and families, offering a space where others truly understand the journey.

Research and the Hope Ahead

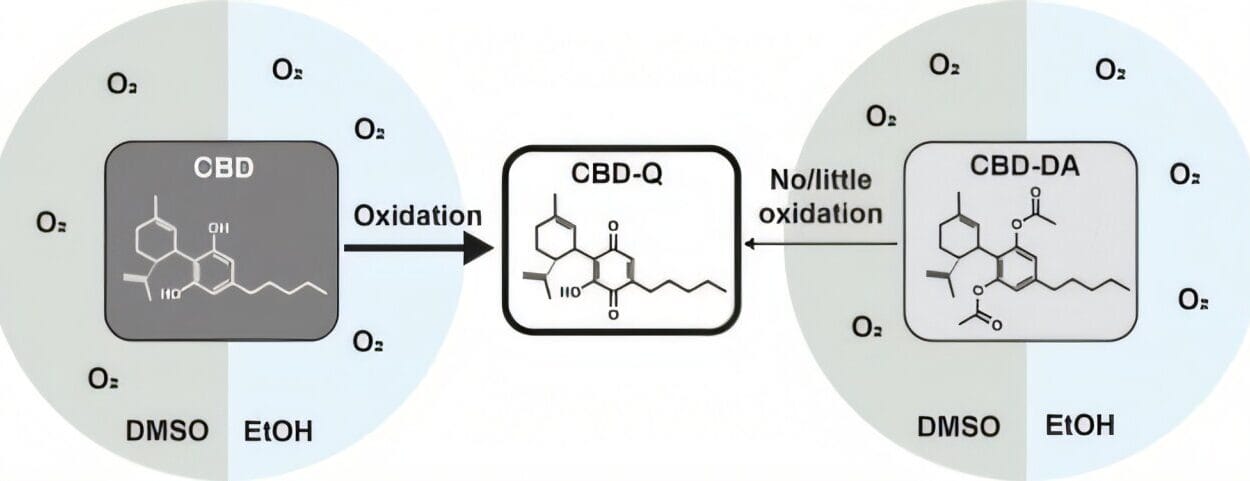

The past few decades have seen major progress in understanding Huntington’s disease. The discovery of the HTT gene in 1993 opened the door to genetic testing, improved diagnosis, and the possibility of targeted therapies. Scientists are now exploring treatments aimed at lowering levels of the mutant huntingtin protein, using techniques like antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) and RNA interference.

Early clinical trials have shown both promise and setbacks, as the complexity of the brain and the disease itself challenge researchers. But the momentum is real. Every failure teaches something new, and every partial success builds hope that a disease-modifying treatment may come within our lifetime.

Gene-editing technologies, like CRISPR, raise the possibility of correcting the mutation before symptoms even begin, though such approaches face enormous technical and ethical challenges.

The Human Side of Science

Beyond the labs and the medical journals, Huntington’s disease is a daily reality for thousands of families worldwide. It’s a teenager watching their parent lose the ability to walk. It’s a young adult wrestling with whether to be tested. It’s a caregiver learning how to help a loved one eat without choking, even as they grieve the gradual loss of the person they knew.

These human stories drive the urgency of research. They remind scientists that every data point in a trial represents a living person with dreams, relationships, and fears.

Living With, and Beyond, the Disease

Some people with Huntington’s disease find ways to continue working, creating, and loving even as symptoms progress. Humor, art, and connection can coexist with the disease’s challenges. Families often describe a deepening of bonds, a recognition of what truly matters when time feels finite.

Yet the need for better treatments, for a cure, remains pressing. Huntington’s disease may be written in the DNA, but it is not the only thing that defines a person. What defines them, too, is resilience, love, and the courage to face an uncertain tomorrow.