Obesity is more than just excess body fat. It is a complex, chronic disease in its own right—shaped by genetics, behavior, environment, and biology. What begins as an imbalance between calories consumed and calories burned can evolve into a persistent metabolic dysfunction that changes the very fabric of a person’s health.

When body fat accumulates beyond a healthy level, especially in the form of visceral fat wrapped around internal organs, it doesn’t just sit there quietly. Fat cells are not inert storage units. They are biologically active tissues that send signals to the rest of the body. These signals can either keep the body running smoothly or, in the case of obesity, disrupt the delicate orchestration of hormones, inflammation, and metabolism. Over time, this disruption fuels the development of chronic diseases that can last a lifetime.

How Fat Becomes a Biochemical Saboteur

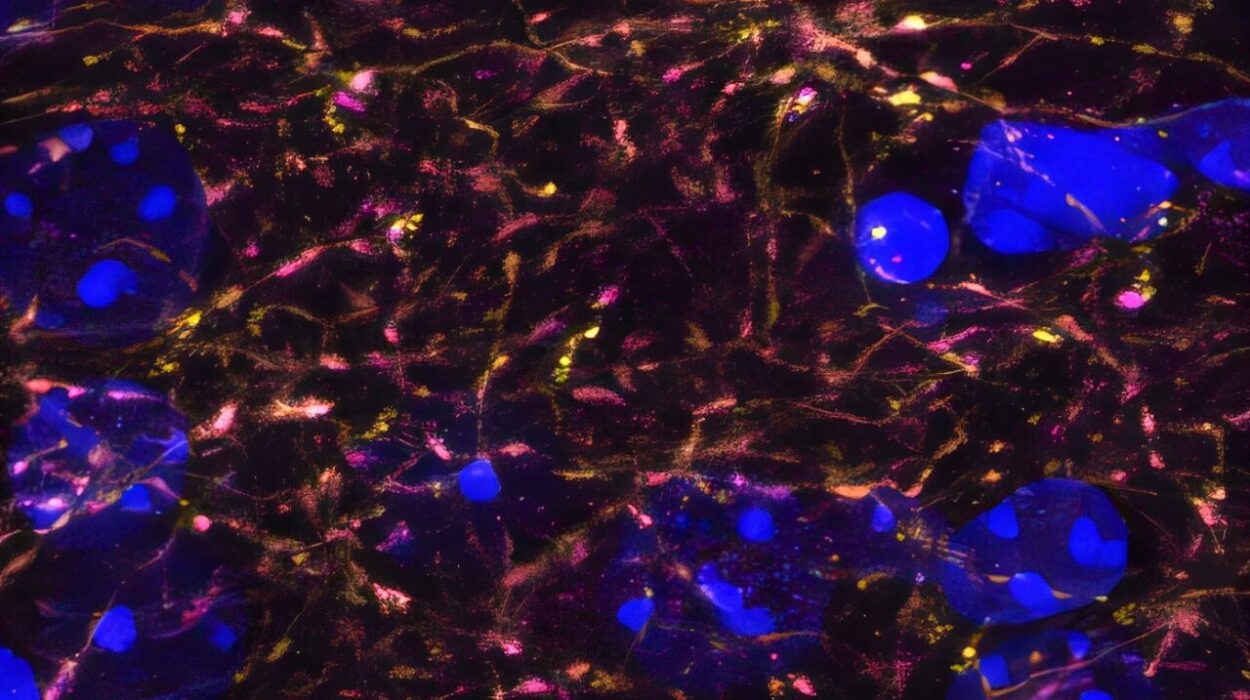

One of the most dangerous effects of obesity is its transformation of fat tissue into a hub of inflammation. Normally, fat stores energy and helps regulate certain hormones, like leptin, which controls hunger, and adiponectin, which affects how our cells use insulin. But in obesity, fat tissue becomes overgrown and crowded. As fat cells enlarge, they struggle to maintain balance. Some even begin to die, triggering an immune response.

The immune system dispatches macrophages—white blood cells that normally help clean up damage—to the fat tissue. There, they release inflammatory chemicals called cytokines. These cytokines—like tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6—signal throughout the body that something is wrong. But instead of healing the body, this low-grade, chronic inflammation creates more harm. It interferes with insulin, damages blood vessels, disturbs appetite regulation, and contributes to disease in almost every major organ system.

This process is slow and insidious. It doesn’t feel like an infection. There’s no fever, no swelling, no obvious wound. Yet the biochemical war inside the body reshapes physiology in ways that make people more vulnerable to long-term illness.

The Link Between Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes

Perhaps the most well-known and direct consequence of obesity is its connection to type 2 diabetes. In a healthy body, insulin acts as a key that allows glucose (sugar) to enter cells, where it’s used for energy. But in people with obesity, especially those with excess belly fat, cells become resistant to insulin’s effects.

The body compensates by producing more insulin, but over time, the pancreas becomes overworked and starts to fail. This leads to rising blood sugar levels and, eventually, the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. The condition is not just about sugar—it affects blood vessels, nerves, kidneys, and the eyes. It increases the risk of heart disease and stroke, and it contributes to fatigue, infections, and amputations.

Obesity doesn’t just raise the risk of developing diabetes—it makes the disease harder to control. People with obesity and diabetes often require higher doses of medication. They may face complications earlier and more frequently. And since the inflammatory environment of obesity interferes with insulin action, weight loss becomes more difficult even as blood sugar levels climb.

The Heart Struggles Under the Weight

The cardiovascular system is another major victim of obesity’s burden. Excess fat tissue demands more oxygen and nutrients, forcing the heart to pump harder and faster. Over time, this increased workload causes the heart muscle to thicken, especially the left ventricle. A thicker heart may sound strong, but it actually becomes less efficient and more prone to failure.

Obesity is closely tied to hypertension, or high blood pressure. As the volume of blood needed to nourish the body rises, the pressure against arterial walls increases. Blood vessels themselves also change. They become stiffer and narrower, less able to adapt to the body’s needs. This increases the risk of stroke, heart attacks, and heart failure.

Blood lipid levels also take a hit. Obesity tends to raise LDL cholesterol—the so-called “bad” cholesterol—while lowering HDL, the “good” cholesterol. It often increases triglycerides as well. Together, these changes create a recipe for atherosclerosis, the dangerous buildup of plaque inside arteries. As plaques grow, they restrict blood flow and can rupture, leading to sudden, life-threatening events.

Breathing Becomes a Battle

For the lungs, obesity is a literal weight pressing down on their ability to expand. Excess fat on the chest and abdomen limits lung volume. People with obesity often experience breathlessness during even mild exertion—not because their lungs are weak, but because their mechanical ability to breathe is impaired.

Obesity also increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea, a condition where the airway repeatedly collapses during sleep, causing frequent awakenings and drops in oxygen levels. Sleep apnea does more than make people tired—it raises blood pressure, strains the heart, and increases the risk of arrhythmias and stroke. It disrupts metabolism and intensifies insulin resistance, creating a vicious cycle.

In severe cases, obesity hypoventilation syndrome can occur, where the body literally fails to breathe deeply enough to maintain normal oxygen and carbon dioxide levels. These patients may suffer from chronic fatigue, confusion, and even heart failure.

The Liver Bears the Silent Scars

The liver, a vital organ of detoxification and metabolism, quietly suffers under the influence of obesity. In many people with obesity, fat begins to accumulate in the liver itself—a condition called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Left unchecked, it can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), where inflammation and fibrosis damage liver cells.

This condition is particularly insidious because it often causes no symptoms until advanced stages. Yet it is now one of the leading causes of liver failure and liver transplantation in the Western world. The rise in NAFLD mirrors the rise in obesity and type 2 diabetes, forming what experts call the metabolic syndrome.

Unlike hepatitis caused by a virus or alcohol, this form of liver disease is driven by insulin resistance, lipid imbalances, and chronic inflammation. As fat chokes liver cells, it disrupts their function and promotes scarring. In time, this scarring can become cirrhosis—a permanent and life-threatening state.

Joints and Bones Strain to Keep Pace

Obesity is also an orthopedic problem. Joints are mechanical structures designed to carry weight. When that weight becomes excessive, wear and tear accelerate. This is especially true in the knees, hips, and lower back, where every extra pound puts several pounds of added pressure with each step.

Osteoarthritis, a degenerative joint disease, becomes more common and more severe in people with obesity. The cartilage that cushions joints wears away faster, leading to pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility. The inflammation associated with obesity can also exacerbate joint damage.

Beyond joints, bones themselves are affected. While more weight might seem to strengthen bones through increased load, the reality is more complex. Obesity changes bone remodeling dynamics, potentially weakening the internal structure and increasing the risk of fractures—especially in the context of poor nutrition or vitamin D deficiency, which are also more common in people with obesity.

Cancer Risks Multiply in the Shadow of Fat

It may surprise many to learn that obesity is now considered the second-leading preventable cause of cancer, right after smoking. The link between fat and cancer is not fully understood, but it is real and growing. Obesity increases the risk of at least 13 different cancers, including breast, colon, endometrial, kidney, pancreatic, and liver cancers.

Fat tissue alters hormone levels, particularly estrogen, which is associated with breast and endometrial cancers. It also increases levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors, which can promote cell proliferation and reduce cell death—a dangerous combination when mutated cells are present.

The inflammatory environment of obesity can also contribute to DNA damage and interfere with the immune system’s ability to detect and destroy early cancer cells. In this way, fat tissue becomes not just a passive risk factor but an active player in tumor development and progression.

Mental Health Suffers in a Hidden Feedback Loop

The relationship between obesity and mental health is complicated and deeply intertwined. On one hand, obesity increases the risk of depression, anxiety, and social isolation. On the other hand, depression can lead to poor dietary choices, reduced activity, and weight gain. The cycle feeds itself.

Neurobiologically, the same pathways that regulate hunger and satiety also influence mood. Inflammatory signals from fat tissue can affect neurotransmitter systems like serotonin and dopamine, contributing to depressive symptoms. People with obesity often face stigma and discrimination, which further damages self-esteem and mental well-being.

Psychological distress can lead to emotional eating, creating a feedback loop that is difficult to escape. And because mental health conditions are often underdiagnosed in people with obesity, the suffering may go unrecognized and untreated.

The Burden of Obesity on Reproductive and Hormonal Health

Obesity also disrupts hormonal systems in ways that affect reproductive health in both men and women. In women, excess fat can cause irregular menstrual cycles, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and infertility. In men, obesity lowers testosterone levels, decreases sperm quality, and increases the risk of erectile dysfunction.

Pregnancy itself becomes more complicated. Obese women face higher risks of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean delivery. Their children are also more likely to become obese and develop metabolic disorders—a legacy passed not just through genes, but through epigenetic and environmental influences in the womb.

Obesity also influences thyroid function and can contribute to hypothyroidism, which in turn may worsen weight gain and fatigue. Hormones like cortisol, produced in response to stress, are also dysregulated, contributing to abdominal fat accumulation and further metabolic dysfunction.

The Challenge of Reversing the Trend

Understanding the connection between obesity and chronic disease is only the first step. Addressing it requires far more than willpower or personal responsibility. Obesity is shaped by the environments we live in—food deserts, sedentary jobs, stress-filled lives, and social inequity all play a role.

Weight loss is difficult and complex, often requiring sustained lifestyle changes, medical interventions, and sometimes surgery. Even modest reductions in weight—5 to 10 percent—can significantly improve blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol levels. But keeping the weight off is notoriously challenging.

The body resists weight loss by lowering metabolism and increasing hunger signals. It remembers its highest weight and tries to return to it. That’s why obesity is now classified as a chronic disease, not just a temporary condition. It demands long-term management and support, not blame or shame.

Hope Through Science and Compassion

Despite its challenges, obesity is not a hopeless condition. Advances in medicine are providing new tools—from GLP-1 agonist drugs that improve both weight and diabetes control, to innovative surgical techniques and better public health strategies. More importantly, the conversation around obesity is shifting.

We are beginning to recognize that people with obesity deserve the same respect, support, and evidence-based care as anyone with a chronic illness. We’re learning that sustainable health is about more than numbers on a scale—it’s about healing the systems that gave rise to obesity in the first place.

Ultimately, obesity’s contribution to chronic disease is not a story of failure, but a call to action. By understanding how fat becomes pathological, we can begin to disarm it. By listening to science and showing compassion, we can turn the tide on one of the greatest health challenges of our time.