Metabolic syndrome sounds like the name of a single disease, but in reality, it is a complex and dangerous cluster of conditions working together in secret to undermine health. Often developing silently and gradually, this condition has become a modern epidemic—one that increases the risk of some of the most feared diseases of our time, including heart attacks, strokes, and type 2 diabetes.

While its name might seem clinical and abstract, metabolic syndrome is both widespread and intensely personal. It develops deep within our cells and organs, driven by a web of biological imbalances and lifestyle factors. As societies have modernized and food systems have industrialized, metabolic syndrome has spread like wildfire, becoming a major public health crisis in both affluent and developing nations. And yet, despite its prevalence, it often goes undiagnosed until serious complications arise.

To understand what metabolic syndrome truly is, we need to explore the inner workings of the human body—how metabolism operates, how it becomes disrupted, and what happens when vital processes begin to fall out of sync. This journey will take us through the landscape of insulin, cholesterol, blood pressure, and waistlines, revealing the many ways in which the body’s internal chemistry can turn against itself.

The Machinery of Metabolism

At its core, metabolism is the sum of all chemical reactions that keep your body alive and functioning. It includes everything from the breakdown of nutrients for energy to the synthesis of new molecules for growth and repair. Think of it as the engine room of a ship—constantly working behind the scenes to maintain the vessel’s operation.

But like any engine, the metabolic system can falter. Metabolic syndrome is what happens when several critical components of this engine begin to malfunction simultaneously. Specifically, it refers to a collection of risk factors that often appear together. These typically include elevated blood sugar, high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol or triglyceride levels, and excess fat around the abdomen.

Having one of these risk factors on its own doesn’t mean you have metabolic syndrome. But when three or more occur together, they create a dangerous synergy that multiplies the risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

How Insulin Resistance Starts the Chain Reaction

One of the key drivers of metabolic syndrome is insulin resistance—a state in which the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin, the hormone responsible for allowing glucose to enter cells from the bloodstream. When this system fails, blood sugar levels begin to rise, prompting the pancreas to produce even more insulin in a desperate attempt to restore balance.

This condition often begins quietly, with no immediate symptoms. But beneath the surface, a storm is brewing. The excess insulin in the bloodstream can disrupt fat metabolism, encourage fat storage in the abdomen, and increase inflammation throughout the body. It also affects how the liver processes lipids, leading to abnormal cholesterol and triglyceride levels.

Insulin resistance doesn’t just fuel high blood sugar—it contributes to almost every other component of metabolic syndrome. It is the spark that ignites a systemic fire, linking organs and systems in a cascade of dysfunction.

The Waistline Warning Sign

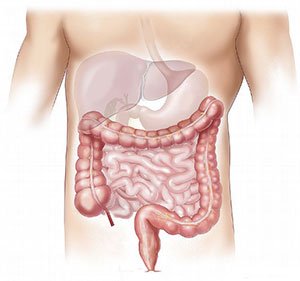

One of the most visible hallmarks of metabolic syndrome is central obesity—also known as visceral or abdominal fat. This isn’t just about appearance; it’s about biology. Visceral fat behaves differently than fat stored elsewhere in the body. It is hormonally active, releasing inflammatory molecules and hormones that interfere with normal metabolism.

Waist circumference is a strong predictor of metabolic syndrome. For many health professionals, it’s the first red flag. Excess abdominal fat is particularly harmful because it surrounds vital organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines, altering their function and releasing chemicals that worsen insulin resistance.

What makes central obesity especially concerning is that it can occur even in individuals with normal overall body weight. This phenomenon, sometimes referred to as “TOFI” (thin outside, fat inside), means that a person might appear healthy but still harbor metabolic risk beneath the surface.

The Role of High Blood Pressure and Cholesterol Imbalance

When insulin resistance and visceral fat are in play, blood pressure often begins to rise. Insulin affects how kidneys manage sodium and how blood vessels dilate. When the system is out of balance, blood vessels constrict, blood volume increases, and hypertension emerges. Over time, this puts tremendous strain on the heart and vascular system.

Meanwhile, the liver—bombarded by excess fatty acids and inflammatory signals—begins to alter the way it processes cholesterol. This leads to a specific lipid profile that is characteristic of metabolic syndrome: elevated triglycerides, low levels of HDL (“good”) cholesterol, and small, dense LDL particles, which are more likely to contribute to arterial plaque.

These changes might seem minor on their own, but when combined, they create a perfect storm. Blood vessels become inflamed and damaged, arteries stiffen and clog, and the risk of atherosclerosis soars.

The Inflammation Connection

Underlying all aspects of metabolic syndrome is chronic, low-grade inflammation. Unlike the acute inflammation you might experience when you cut your finger, this type is stealthy and persistent. It smolders quietly, fueled by visceral fat, insulin resistance, and oxidative stress.

Inflammation affects nearly every organ in the body. It can interfere with insulin signaling, damage the lining of blood vessels, and contribute to the progression of fatty liver disease. It also plays a role in the development of cardiovascular disease by promoting the formation of unstable plaques that can rupture and cause heart attacks or strokes.

Markers of inflammation, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), are often elevated in people with metabolic syndrome. Scientists now believe that inflammation is not just a side effect, but a central player in the development and worsening of this condition.

The Rising Tide Across the Globe

Metabolic syndrome is not confined to one population or region. It is a global health issue, affecting hundreds of millions of people. As diets have shifted toward processed foods, sugary drinks, and high-calorie convenience meals, rates of obesity and insulin resistance have skyrocketed.

Urbanization, sedentary lifestyles, and stress also play major roles. The combination of poor diet, lack of physical activity, and chronic stress sets the stage for metabolic chaos. In some parts of the world, traditional diets rich in fiber and healthy fats have been replaced by Western-style eating habits almost overnight, leading to rapid increases in metabolic syndrome prevalence.

What’s particularly troubling is that metabolic syndrome is being diagnosed at younger and younger ages. Children and adolescents are now developing risk factors once reserved for middle-aged adults, suggesting a troubling future if current trends continue.

The Gender and Ethnicity Factors

Metabolic syndrome doesn’t affect everyone equally. Genetics, sex, and ethnicity all play roles in how and why it develops. For instance, women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) often experience insulin resistance and are at increased risk. After menopause, the risk in women rises significantly as hormonal changes affect fat distribution and metabolic function.

Certain populations, including Hispanic, South Asian, Native American, and African American communities, have a higher predisposition to metabolic syndrome. These disparities are influenced by both genetic susceptibilities and socioeconomic factors such as access to healthcare, nutrition, and education.

Understanding these variations is critical. A one-size-fits-all approach to prevention and treatment won’t work in a world as diverse as ours.

Diagnosis and the Power of Early Detection

Detecting metabolic syndrome requires vigilance. It often begins with routine blood tests and a tape measure. Healthcare providers look for specific criteria: a large waist circumference, high fasting blood sugar, elevated blood pressure, high triglycerides, and low HDL cholesterol.

If a person meets at least three of these criteria, they are diagnosed with metabolic syndrome. But the real value lies in catching the signs before they escalate. The earlier the condition is detected, the more likely it can be reversed or managed effectively through lifestyle changes.

Regular check-ups, especially for individuals with family histories of diabetes or heart disease, are essential. So is awareness. Too many people live with metabolic syndrome without knowing it until a heart attack or diabetes diagnosis forces their attention.

Turning Back the Clock with Lifestyle Change

The good news is that metabolic syndrome is not a life sentence. In many cases, it can be reversed or dramatically improved with lifestyle changes. Unlike some conditions that require complex medical treatments, metabolic syndrome often responds powerfully to simple but sustained adjustments.

Physical activity is one of the most potent tools. Even moderate exercise—like brisk walking for 30 minutes a day—can improve insulin sensitivity, lower blood pressure, and reduce abdominal fat. Resistance training adds further benefits by increasing muscle mass, which helps regulate blood sugar.

Diet also plays a pivotal role. Reducing refined carbohydrates and added sugars, increasing fiber intake, and incorporating healthy fats from sources like olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish can stabilize metabolism. The Mediterranean diet, in particular, has shown remarkable success in improving metabolic health.

Weight loss, even as little as five to ten percent of body weight, can have profound effects. It improves nearly every component of metabolic syndrome and can sometimes restore normal metabolic function entirely.

When Medication Becomes Necessary

For some individuals, lifestyle changes are not enough, especially when metabolic syndrome is advanced. In such cases, medications may be prescribed to manage specific components. These may include drugs for hypertension, statins to control cholesterol, or metformin to improve insulin sensitivity.

While medication can be life-saving, it works best when combined with behavioral changes. The goal is not to rely on pills alone, but to create a comprehensive strategy that addresses both the symptoms and the root causes of metabolic dysfunction.

Researchers are also exploring newer medications that target multiple aspects of metabolic syndrome at once. Some diabetes drugs, for example, have shown promise in reducing weight and improving heart health simultaneously.

The Future of Prevention and Public Health

The fight against metabolic syndrome extends beyond the clinic. It requires public health policies that promote healthier food environments, physical activity, and access to preventative care. Taxing sugary drinks, regulating food marketing to children, and creating walkable communities are all strategies that can shift the tide.

Education is equally vital. Teaching people about nutrition, stress management, and the risks of metabolic dysfunction can empower them to take control of their health. Schools, workplaces, and community organizations all have a role to play.

Technology, too, is stepping into the fray. Wearable devices, health apps, and telemedicine offer new ways to monitor and improve metabolic health. Personalized medicine, based on genetic and lifestyle data, may one day allow for highly tailored interventions that prevent metabolic syndrome before it starts.

A Wake-Up Call for a Modern World

Metabolic syndrome is not just a medical condition—it is a mirror reflecting the challenges of modern life. It reveals the consequences of our diets, our habits, our environments, and our systems of care. It exposes the ways in which convenience and speed can come at the cost of long-term health.

But it also offers a powerful opportunity. Because it is so closely linked to modifiable behaviors, it is one of the most preventable and reversible health conditions we face. By recognizing the warning signs and taking action early, individuals can dramatically reduce their risk of serious illness and reclaim control over their well-being.

In many ways, understanding metabolic syndrome is a journey into understanding ourselves—our biology, our behaviors, and our place in a rapidly changing world. And perhaps more importantly, it is a call to action. One that asks not just what is happening inside our bodies, but what we can do, collectively and individually, to change the outcome.