Coral reefs are often celebrated for their dazzling colors and extraordinary biodiversity. They’re home to countless species and a vital part of the marine ecosystem. But what if we told you that these underwater marvels have been quietly conducting a much deeper, more profound role in shaping the Earth’s climate for over 250 million years?

This isn’t just about coral reefs being beautiful. According to new research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, coral reefs have long acted as crucial regulators of Earth’s carbon and climate cycles. They have not merely responded to climate change; they have been actively setting the rhythm of how the planet recovers from carbon dioxide (CO₂) shocks.

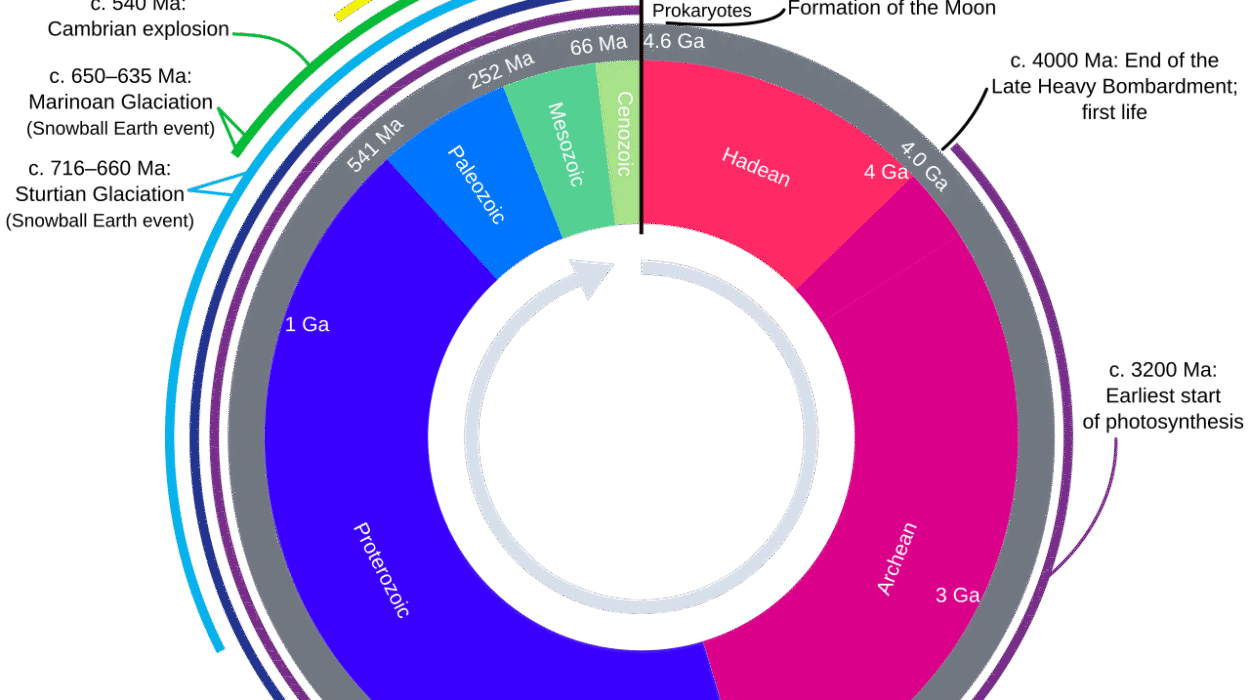

Scientists have long known that Earth’s climate is heavily influenced by its carbon cycle—the natural process by which carbon moves through the atmosphere, oceans, and land. What this groundbreaking study reveals, however, is that coral reefs have played an active part in this cycle. Through their rise and fall, they’ve controlled the pace at which the planet heals from the major disruptions in CO₂ levels that have occurred throughout Earth’s history.

Two Modes of Earth’s Carbon Cycle

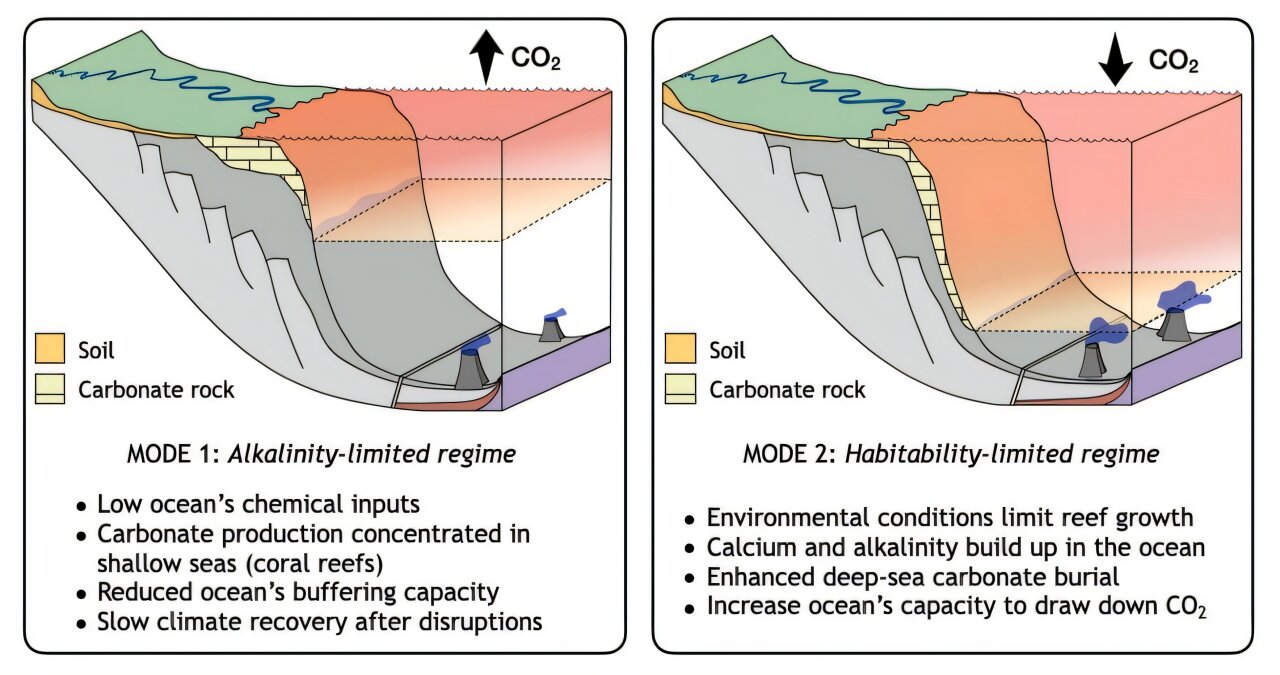

The study, conducted by researchers from the University of Sydney and Université Grenoble Alpes, combined cutting-edge climate simulations with ecological models to look back at the Earth’s shallow-water carbonate production all the way to the Triassic period. The results revealed a fascinating pattern: Earth’s climate oscillates between two distinct modes that control how quickly it recovers from disruptions to the carbon cycle.

In one of these modes, when tropical reefs are widespread and healthy, carbonate (a key compound in the Earth’s carbon cycle) accumulates in shallow seas. This accumulation reduces the chemical exchange with the deep ocean, slowing down the biological pump—a process where marine organisms draw carbon from the atmosphere and store it in the ocean. As a result, the planet’s recovery from carbon shocks slows.

In the second mode, when reefs begin to collapse—either due to tectonic shifts or changes in sea level—carbonates start to build up in the deep ocean. This shift triggers the flourishing of nannoplankton, the tiny marine organisms that play a crucial role in drawing down atmospheric carbon. This shift in the balance of carbonate burial accelerates the Earth’s recovery, helping stabilize the climate more quickly.

Associate Professor Tristan Salles, the lead author of the study, explained it like this: “Reefs didn’t just respond to climate change—they helped set the tempo of recovery.”

Reefs as Active Climate Modulators

These findings completely change the way we think about coral reefs. No longer are they just passive recorders of environmental change, but rather active participants in Earth’s climate system. They have, in fact, served as powerful modulators of the planet’s buffering capacity—the ability of Earth’s systems to absorb and manage carbon and other greenhouse gases.

This research suggests that shallow-water carbonate systems, including coral reefs, have been crucial in dictating how quickly Earth’s climate can return to a stable state after major disturbances. They are not just home to biodiversity; they are key players in the intricate dance of the carbon cycle, helping to regulate the Earth’s climate over long geological timescales.

Co-lead author Dr. Laurent Husson, from the CNRS—UGA, emphasized how important this “shifting balance” has been: “These switches profoundly alter the biogeochemical equilibrium,” he said. He pointed to a particularly significant event in Earth’s history—the expansion of planktonic life—explaining that this explosion of plankton occurred precisely when shallow reefs were “turned down” by the Earth system. This shift affected the ocean’s biological pump and, in turn, altered the climate’s recovery.

By shedding light on this dynamic, the study shows that coral reefs have been essential not just for marine life but also for the stability of the planet’s climate. These underwater ecosystems have helped govern the planet’s ability to recover from global carbon disruptions, making them far more than the “rainforests of the sea.”

Lessons for the Present

Although the research focuses on the deep past, its implications for the future are clear. Today, modern coral reefs are in crisis, rapidly declining due to warming oceans, ocean acidification, and human-driven CO₂ emissions. The current trajectory of reef degradation suggests that Earth may be about to enter a phase of carbon recovery similar to ancient episodes of reef collapse.

As the reefs continue to shrink, carbonate burial could shift from shallow reefs to the deep ocean, where plankton and other calcifying organisms would take over the task of drawing down carbon. In theory, this could help the planet absorb excess CO₂, but the process would come at a steep ecological cost. The organisms responsible for this deep-sea carbonate burial—such as plankton—are themselves under threat from acidifying oceans and warming waters.

For this stabilizing effect to work, it would take place only after severe and irreversible losses to marine ecosystems. Associate Professor Salles warned, “From our perspective on the past 250 million years, we know the Earth system will eventually recover from the massive carbon disruption we are now entering. But this recovery will not occur on human timescales. Our study shows that geological recovery requires thousands to hundreds of thousands of years.”

In other words, while the Earth will eventually find a way to stabilize, this process will take far longer than human societies can afford. The rapid decline of coral reefs today could delay or even complicate the planet’s natural recovery, leaving future generations to face a drastically altered world.

Why This Research Matters

The findings of this study are crucial not only for our understanding of Earth’s past but also for our approach to the future. As the climate crisis worsens and coral reefs continue to degrade, the loss of these vital ecosystems has far-reaching consequences for both biodiversity and climate stability.

If we are to mitigate the worst effects of climate change and avoid pushing the planet into an irreversible state, we must understand the role that reefs play in regulating the Earth’s carbon cycle. The collapse of reefs in the past has triggered dramatic shifts in how carbon is stored and cycled through the oceans. If we don’t act swiftly to protect these ecosystems today, we may be faced with a future where the planet’s recovery comes too late for us to prevent the worst outcomes.

In this light, the research serves as both a warning and a call to action. Coral reefs are not merely beautiful and biodiverse; they are the Earth’s climate regulators, and their fate is intricately tied to the future of our planet. The sooner we acknowledge their role in climate regulation, the better our chances of mitigating the climate crisis and protecting the delicate balance of life on Earth.

More information: Tristan Salles et al, Carbonate burial regimes, the Meso-Cenozoic climate, and nannoplankton expansion, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2516468122. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2516468122