Nestled discreetly at the base of your neck lies a small, butterfly-shaped gland known as the thyroid. Despite its unassuming size, this gland plays a vital role in regulating your metabolism, energy levels, temperature, and even your mood. It does all this by producing hormones—tiny chemical messengers that orchestrate a symphony of bodily functions. But for millions around the world, this crucial gland becomes the target of a perplexing and often misunderstood internal assault. The attacker? The body’s own immune system.

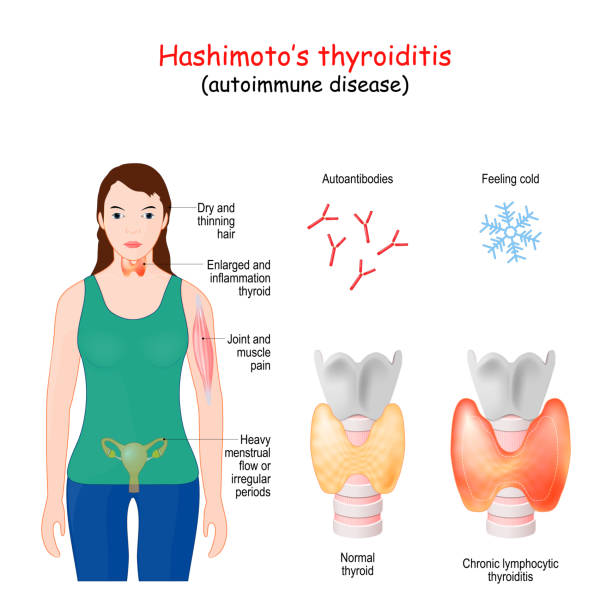

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is an autoimmune disease, and one of the most common causes of hypothyroidism, or underactive thyroid. It’s a condition where the immune system, designed to protect the body, mistakenly identifies the thyroid gland as a threat and begins to destroy it, piece by piece, over time. Named after Dr. Hakaru Hashimoto, who first described it in 1912, this chronic illness has since revealed itself to be far more widespread and insidious than once believed.

The Slow Burn of an Invisible War

Unlike some diseases that strike suddenly and dramatically, Hashimoto’s operates like a slow-burning fire. Its symptoms often emerge gradually, quietly seeping into a person’s life until the very fabric of their health and well-being begins to unravel. Fatigue begins to feel like a constant companion, weight gain stubbornly resists diet and exercise, and emotions fluctuate in ways that seem disconnected from external circumstances. Hair thins, skin dries, memory fogs, and the simple act of getting through the day can begin to feel like a monumental task.

This creeping, almost stealthy progression is one of the reasons Hashimoto’s is so frequently misunderstood or misdiagnosed. Its symptoms can mimic depression, menopause, chronic fatigue syndrome, and a host of other conditions. Doctors may attribute a patient’s complaints to stress, aging, or lifestyle factors, missing the deeper dysfunction smoldering at the core of the thyroid gland.

For many patients, the journey to diagnosis is long and frustrating, filled with self-doubt and unanswered questions. Yet behind these seemingly disconnected symptoms is a clear biological process: immune cells flooding the thyroid, attacking it, inflaming it, and eventually impairing its ability to produce the very hormones that keep the body in balance.

When the Body Turns Against Itself

To truly understand Hashimoto’s, it helps to delve into the broader world of autoimmune disease—a realm where the body’s defense system goes rogue. The immune system is a powerful force, trained from birth to recognize and eliminate threats. But in autoimmune conditions like Hashimoto’s, that finely tuned detection system breaks down. For reasons not yet fully understood, the immune system begins mistaking the thyroid’s tissue for a hostile invader.

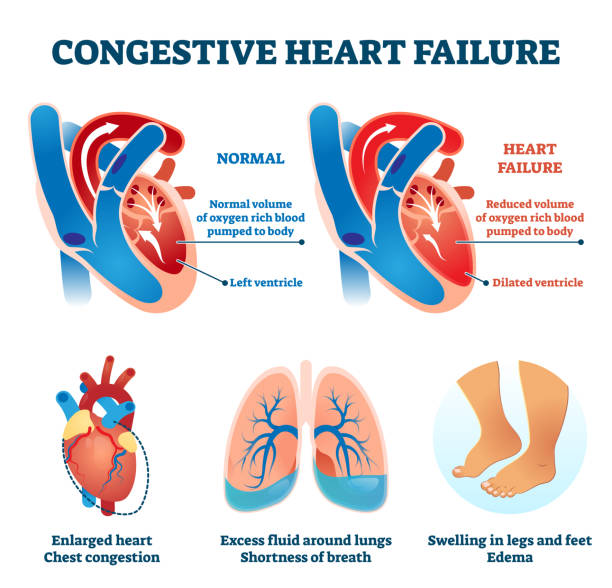

What follows is a chronic state of inflammation. The thyroid becomes a battlefield, under siege from immune cells that launch wave after wave of attacks. Over time, this persistent inflammation scars and weakens the gland, reducing its ability to produce thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3)—the two primary hormones that regulate metabolism and energy.

The effects ripple outward. Every cell in the body relies on thyroid hormones to function properly. When those hormones dwindle, the entire body begins to slow down. Muscles ache, digestion stalls, the brain feels sluggish, and emotions waver. What might seem like isolated symptoms are in fact the cascading consequences of an immune war waged at the center of the endocrine system.

Who Hashimoto’s Targets—and Why

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis does not discriminate entirely, but certain populations are more vulnerable. Women are overwhelmingly more likely to develop the condition than men—by a factor of up to ten to one. The disease typically appears between the ages of 30 and 50, but it can affect younger individuals, even children. Family history is also a powerful predictor; autoimmune diseases tend to run in families, and someone with a parent or sibling who has Hashimoto’s or another autoimmune condition is more likely to develop it themselves.

While the exact causes remain elusive, researchers believe that Hashimoto’s arises from a complex interplay of genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers. Viral infections, chronic stress, hormonal changes, excessive iodine intake, and even gut health have all been implicated. In many cases, it’s not a single factor but a convergence of several that tips the immune system into dysfunction.

Interestingly, a growing body of research is exploring the role of the microbiome—the vast ecosystem of bacteria that inhabit the gut—in autoimmune disease. The immune system and the gut are closely intertwined, and disruptions in gut flora may set the stage for immune miscommunication. In this view, Hashimoto’s might be as much about the terrain of the body as it is about the immune cells themselves.

The Diagnostic Puzzle

Identifying Hashimoto’s is not always straightforward. Many people experience symptoms for years before a doctor considers testing their thyroid function. When suspicion finally turns toward the thyroid, blood tests are the first step. Doctors typically measure levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), as well as free T4. Elevated TSH and low T4 suggest hypothyroidism, but this alone does not confirm Hashimoto’s.

To determine whether the cause is autoimmune, additional tests are needed—specifically, antibodies such as anti-thyroid peroxidase (anti-TPO) and anti-thyroglobulin. These antibodies are markers that the immune system is targeting the thyroid. Their presence, along with symptoms and abnormal thyroid hormone levels, solidifies a diagnosis.

However, not all patients with Hashimoto’s have high antibodies, and not all with high antibodies have symptoms. The condition exists on a spectrum, with some people harboring immune activity against the thyroid for years before symptoms emerge. This silent stage of the disease adds another layer of complexity, and also an opportunity: early detection could potentially allow for interventions that delay or mitigate the full onset of hypothyroidism.

Living Under the Weight of Hypothyroidism

When Hashimoto’s progresses far enough to cause hypothyroidism, the body begins to suffer the consequences of slowed metabolism. Cold sensitivity becomes pronounced, energy plummets, and even the heart rate may drop. Weight creeps up despite unchanged eating habits. The brain slows too, with concentration and memory becoming clouded—a phenomenon often referred to as “thyroid brain fog.”

For many, the emotional toll is as significant as the physical one. Depression is a common companion, exacerbated by hormonal imbalances that affect neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine. Relationships strain under the burden of unexplained irritability and exhaustion. Social lives shrink, ambitions dim, and the vibrant person one used to be may feel like a distant memory.

The relentlessness of the condition—its chronicity, its ambiguity, its invisibility—can be profoundly isolating. Yet for all its challenges, Hashimoto’s is a manageable condition, and with proper treatment, many people regain their vitality and reclaim their lives.

The Pill That Changes Everything—And Nothing

The standard treatment for Hashimoto’s-related hypothyroidism is straightforward in theory: replace the missing hormones with synthetic ones. Levothyroxine, a synthetic form of T4, is one of the most commonly prescribed medications in the world. Taken once daily, it can restore normal thyroid hormone levels, alleviate symptoms, and stabilize metabolism.

For some patients, this treatment works beautifully. Energy returns, weight stabilizes, mood lifts. But for others, the road is bumpier. Despite taking medication, symptoms may linger. This can happen for several reasons: the dose may not be optimal, absorption may be impaired, or the patient may not be efficiently converting T4 to T3—the more active form of thyroid hormone.

Some patients benefit from combination therapy, which includes synthetic T3 or natural desiccated thyroid extract. This remains a controversial area of treatment, with varying guidelines and patient experiences. The key is personalization—working with a knowledgeable physician who understands the nuances of thyroid function and listens carefully to patient feedback.

Beyond the Pill: Healing the Terrain

While thyroid hormone replacement addresses the hormone deficiency, it does not stop the underlying autoimmune attack. That ongoing immune activity can continue to damage the thyroid and cause inflammation throughout the body. As a result, many patients seek additional ways to support their health—through diet, lifestyle, and holistic practices.

Diet is often the first frontier. Some patients find relief by removing potential inflammatory foods such as gluten, dairy, and processed sugars. The autoimmune protocol (AIP) diet, a more restrictive regimen, aims to reduce inflammation and promote gut healing. Though scientific evidence is still catching up, many patients report improvements in energy, mood, and symptom severity.

Stress management is equally important. Chronic stress can dysregulate the immune system, disrupt hormones, and exacerbate inflammation. Mindfulness practices, gentle exercise like yoga or tai chi, and adequate sleep can all make a measurable difference. Supplements such as selenium, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty acids are sometimes used, though they should always be discussed with a healthcare provider.

These lifestyle approaches are not cures, but they can significantly enhance quality of life, especially when combined with medical treatment. They also empower patients to take an active role in their healing journey—something that can feel deeply grounding in the face of a condition that otherwise makes one feel powerless.

The Emotional Landscape of Hashimoto’s

Chronic illness does not exist in a vacuum. It affects how we see ourselves, how we relate to others, and how we navigate the world. With Hashimoto’s, these emotional reverberations are often profound. The unpredictability of symptoms can make planning difficult. The invisibility of the disease can lead to disbelief or dismissal from others. The daily management—the pills, the labs, the self-monitoring—can feel like a second job.

Yet out of this struggle often emerges strength. Many people with Hashimoto’s become fierce advocates for their health, knowledgeable about nutrition, hormones, and immunology. They build communities, share resources, and support one another. They learn to tune into their bodies in ways most healthy people never have to. They adapt, persist, and thrive—not because the disease is easy, but because they are resilient.

Looking Toward the Horizon

The future of Hashimoto’s research holds promise. Scientists are unraveling the genetic markers associated with the disease, exploring how gut bacteria influence autoimmunity, and developing therapies that may one day modulate the immune system more precisely. Advances in functional medicine are helping clinicians see the body not as a collection of isolated parts, but as an interconnected whole.

What if we could identify Hashimoto’s years before symptoms appear, and intervene before the thyroid is damaged? What if we could retrain the immune system to distinguish friend from foe? What if thyroid hormone replacement could be tailored perfectly to each person’s unique biochemistry? These are not distant dreams—they are active areas of research.

Until then, the best weapon against Hashimoto’s is knowledge. Understanding the disease, recognizing its signs, and advocating for proper care can make all the difference. So can compassion—from doctors, from loved ones, and from oneself.