It starts quietly. A slight stoop in your posture. A bit of back pain that lingers longer than it used to. One day, you trip—not hard, just a small stumble—and suddenly your wrist or hip is fractured. For millions, this is the first warning sign of osteoporosis, a condition often described as a “silent disease” because of how stealthily it weakens the very framework of our bodies—our bones.

Bones feel permanent, don’t they? We think of them as the unchanging core of our physical selves, the silent sentinels under skin and muscle. But bones are not static. They’re living, dynamic tissue, constantly being broken down and rebuilt throughout life. When this balance tips too far in one direction—when more bone is lost than created—we enter dangerous territory.

Osteoporosis is more than a clinical diagnosis. It’s a societal, emotional, and physical challenge that affects families, futures, and the independence of those we love. Understanding it requires both science and empathy—a look not just at calcium and cells, but at what it means to become fragile in a world that rarely slows down for weakness.

Inside the Architecture of Bone

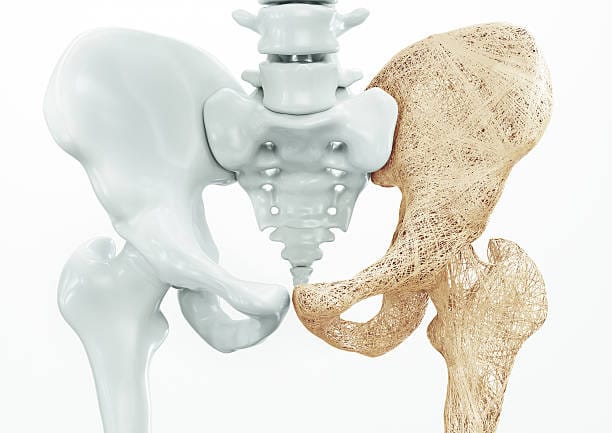

To understand osteoporosis, we must first understand bone itself—not as a rigid structure, but as a living organ. Bone is made primarily of a protein called collagen, which gives it flexibility, and a mineral called hydroxyapatite, rich in calcium and phosphate, which provides hardness. This combination allows bones to be both strong and slightly elastic—capable of bearing immense weight and absorbing shocks.

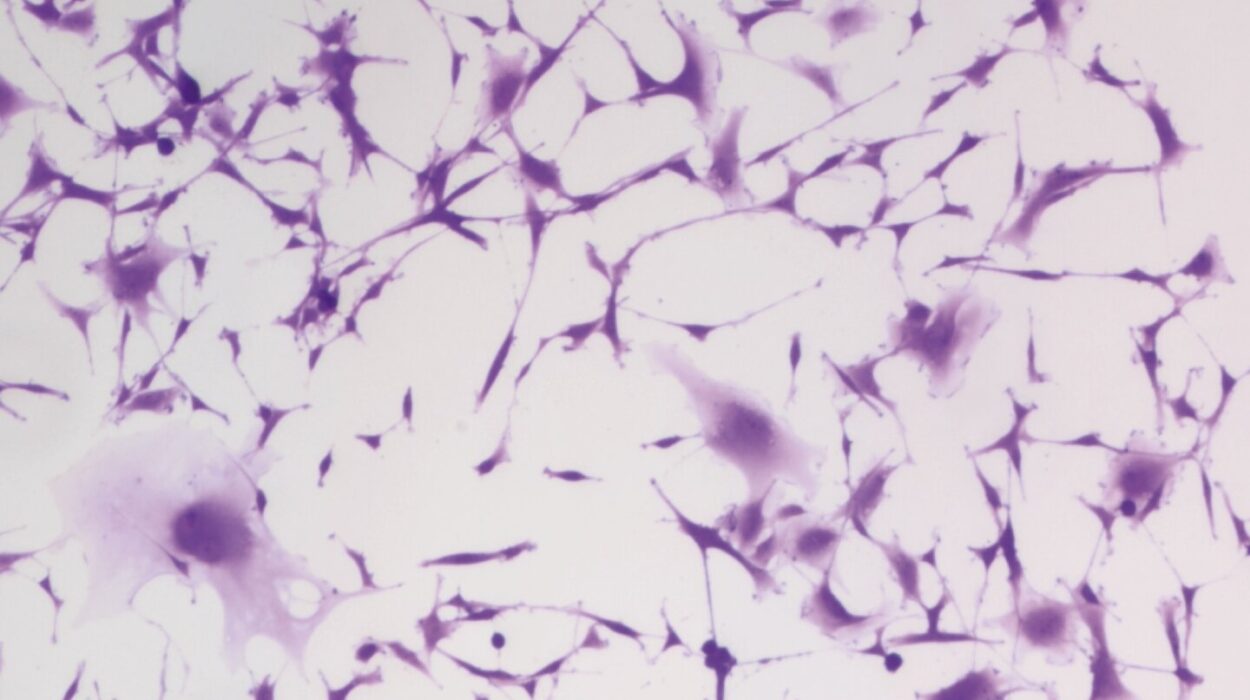

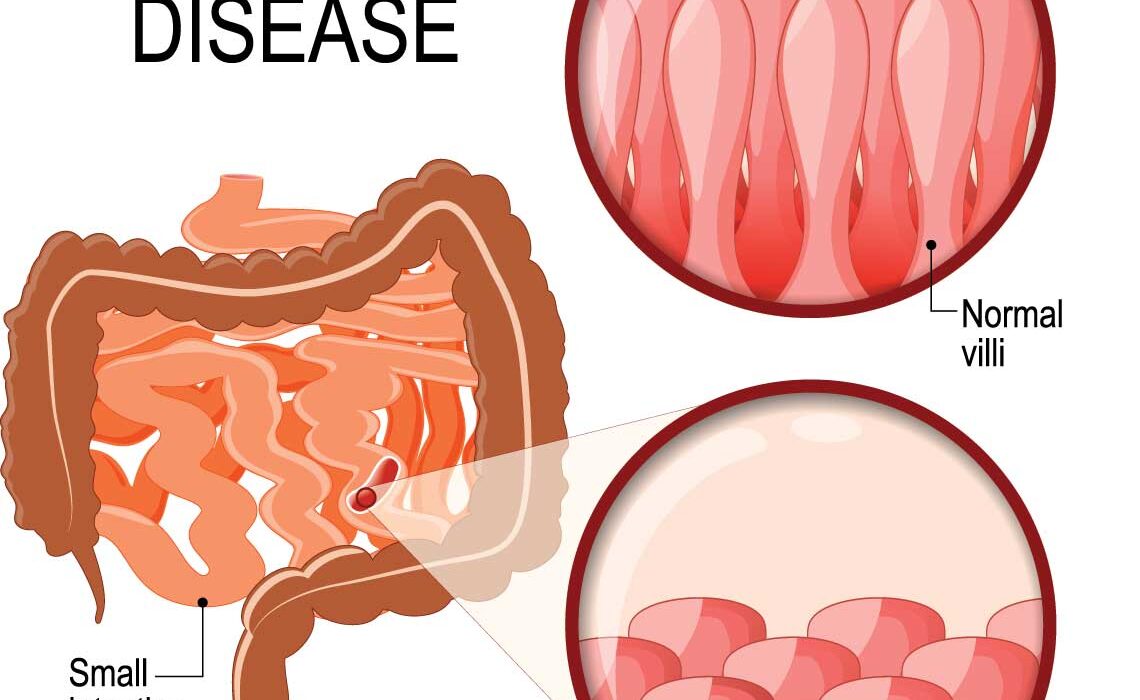

Within the matrix of bone are two main types of tissue: cortical bone, the dense outer layer, and trabecular bone, the spongy inner layer found in the spine, ribs, hips, and wrists. It’s the trabecular bone that often goes first in osteoporosis, its delicate latticework becoming porous and brittle. Imagine a honeycomb slowly being eaten away by invisible forces—that’s the early phase of the disease.

Bone cells are constantly at work. Osteoclasts break down old bone, while osteoblasts build new bone. This process, called remodeling, ensures that bone remains strong, repairing micro-damages from everyday life. In youth, this system is beautifully balanced. But as we age, the scale tips: osteoclasts become more active, and osteoblasts slow down. Without intervention, this imbalance eventually results in bones that can no longer support us the way they once did.

The Early Clues: Risk Factors and Red Flags

Osteoporosis doesn’t strike like a heart attack. It whispers over decades. But the clues are there—genetics, lifestyle, diet, medications, and hormones all play roles in determining who is most at risk.

Women, particularly after menopause, are disproportionately affected. The steep decline in estrogen—a hormone that protects bones—accelerates bone loss. But men aren’t immune. By age 75, men and women are nearly equally likely to suffer osteoporotic fractures. A family history of the disease, a small or thin frame, smoking, excessive alcohol, and low physical activity all increase the risk.

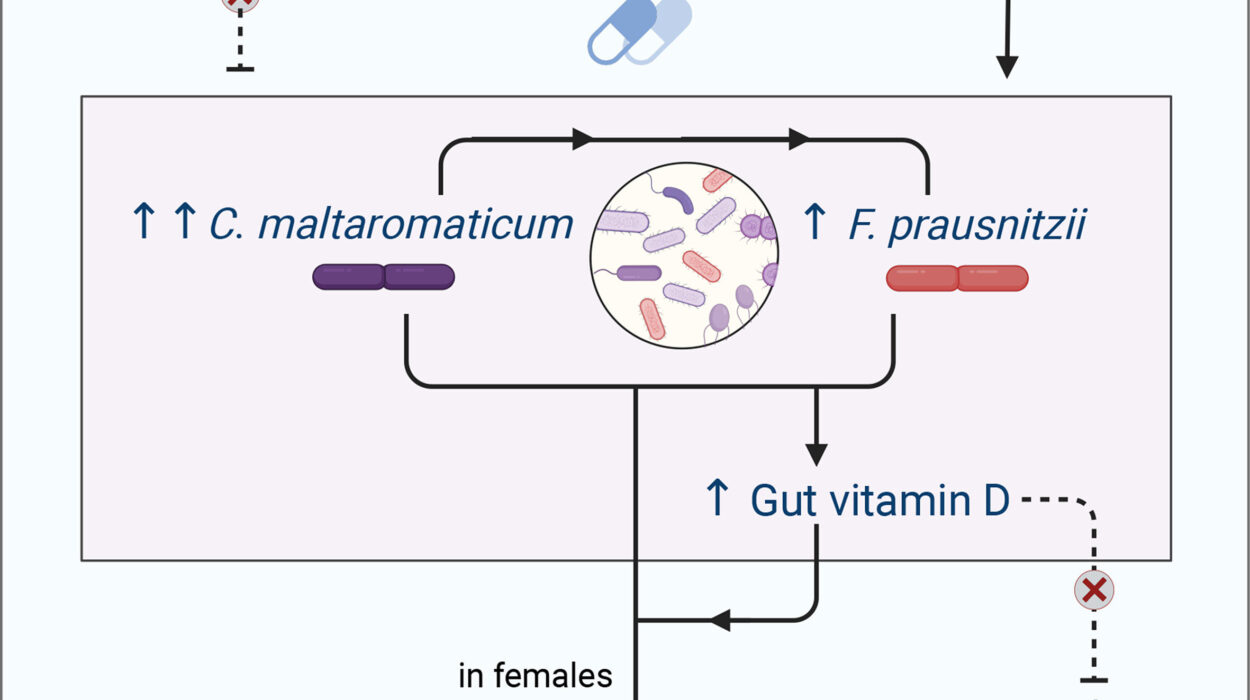

Certain medications, like corticosteroids and some cancer treatments, can compromise bone health. Conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disorders, or chronic kidney disease also raise red flags. And while calcium and vitamin D are important, they’re only pieces of the puzzle. Without movement—especially weight-bearing activity—bones won’t maintain their strength, no matter how much milk you drink.

Fractures, particularly in the spine, hip, and wrist, are often the first sign of osteoporosis. Spinal fractures can occur without any fall at all. They may result in height loss, back pain, or a hunched posture. These are not just cosmetic concerns. A spinal deformity can compress the lungs and digestive organs, leading to complications that extend far beyond the skeleton.

The Diagnosis That Changes Everything

Discovering you have osteoporosis often begins with a DEXA scan, a painless test that measures bone mineral density (BMD). Results are given in T-scores, which compare your bone density to that of a healthy young adult. A score of -1 to -2.5 indicates osteopenia (low bone mass), while a score below -2.5 confirms osteoporosis.

For many, the diagnosis feels like a betrayal by the body—a reminder of mortality. It can trigger fear, shame, even grief. But knowledge is power. A diagnosis is not a death sentence. It’s an invitation to intervene, to build a fortress from the bones that remain.

Doctors may also assess your FRAX score, which estimates your 10-year risk of major osteoporotic fracture. This calculation considers age, gender, weight, height, lifestyle, and health history. Together, these tools help guide treatment, whether lifestyle changes alone or with medication.

The War for Bone: Treatment and Hope

The good news is that osteoporosis is treatable, and sometimes even reversible. Treatment typically begins with calcium and vitamin D supplementation, aiming to provide the raw materials bones need to rebuild. Adults over 50 are generally advised to get 1,200 mg of calcium and 800–1,000 IU of vitamin D daily, though recommendations can vary.

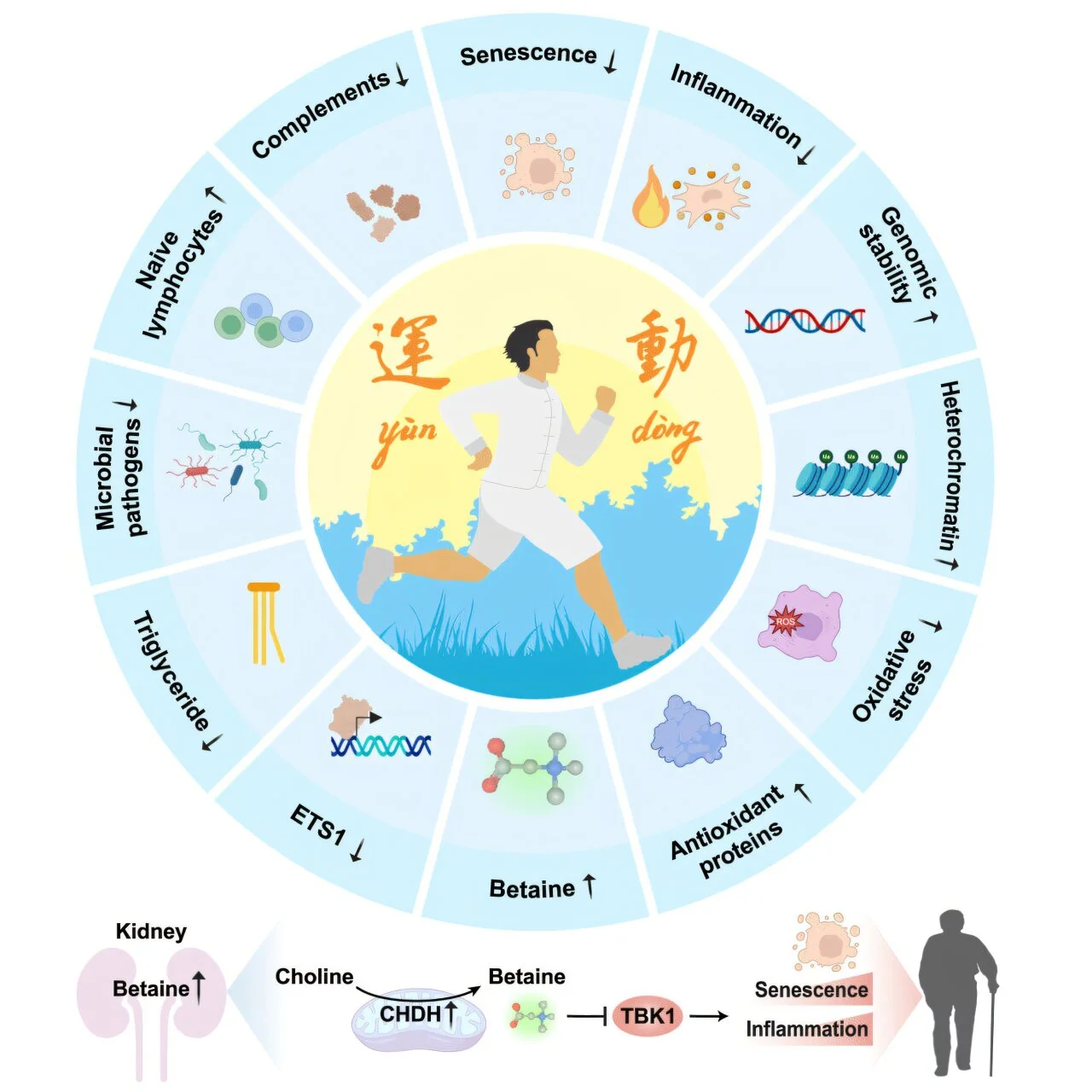

Weight-bearing exercise is medicine for bones. Walking, dancing, hiking, stair climbing, and resistance training stimulate the body to produce more bone. Exercise also improves balance and coordination, reducing the risk of falls—the leading cause of fractures in people with osteoporosis.

For those at higher risk, medications are often needed. These fall into two main categories: antiresorptives, which slow bone loss, and anabolics, which help build new bone.

Bisphosphonates, like alendronate and risedronate, are the most commonly prescribed antiresorptives. They bind to bone surfaces and inhibit osteoclast activity. Denosumab, another antiresorptive, works through a different mechanism but achieves similar results.

Anabolic agents like teriparatide and abaloparatide mimic parathyroid hormone, stimulating new bone growth. A newer option, romosozumab, works both ways—building bone and slowing resorption.

These treatments aren’t without risks—jaw osteonecrosis, gastrointestinal issues, or atypical femur fractures—but for many, the benefits far outweigh the dangers. The choice of therapy depends on fracture risk, tolerance, and medical history. Managing osteoporosis is not one-size-fits-all. It’s a long-term partnership between patient and provider.

Beyond Pills: Living with Fragility and Strength

Osteoporosis forces a confrontation not just with biology, but with identity. People who once carried groceries, climbed stairs, or chased grandchildren may suddenly fear every step. A hip fracture can mean months in a hospital bed, followed by rehab, and in too many cases, a permanent loss of independence.

Yet, the diagnosis can also be transformative. It teaches vigilance—fall-proofing your home, improving lighting, removing trip hazards. It encourages community—exercise classes designed for bone health, support groups where people share stories and strategies. And it demands self-respect—not in vanity, but in valuing the body as it is, not as it once was.

Nutrition becomes a sacred act. Foods rich in calcium—leafy greens, dairy, fortified cereals—become staples. Magnesium, vitamin K2, and phosphorus also join the plate. Sunshine, the body’s primary source of vitamin D, becomes a friend again. Small habits accumulate. Bones remember.

The Gender Divide and Hidden Disparities

While osteoporosis affects both men and women, it has historically been framed as a “women’s disease.” As a result, men are often underdiagnosed and undertreated. By the time a fracture occurs, bone loss may already be severe. This gender bias in screening and awareness costs lives.

The disparities don’t end there. Access to bone health care—screening, medication, follow-up—varies dramatically by race, income, and geography. In many countries, osteoporosis remains underdiagnosed, especially in rural areas. Older adults of color often face systemic barriers to receiving appropriate care, despite being at significant risk.

Fixing this requires more than public health campaigns. It requires rethinking the systems that decide who is seen, who is heard, and who is worthy of preventative care. Because healthy bones are not a luxury. They are a birthright.

Fragility Isn’t Weakness—It’s a Truth We All Share

There is something deeply human about osteoporosis. Beneath the medical terms lies a universal truth: we all grow older. We all become more vulnerable. Our skeletons, once symbols of strength, eventually betray us—not out of cruelty, but because time wears on even the hardest surfaces.

But fragility isn’t failure. Fragility is the price of life. It reminds us to slow down, to pay attention, to protect one another. It gives urgency to connection, to empathy, to compassion.

People with osteoporosis are not broken. They are survivors. They walk more carefully, yes—but they keep walking. They adapt. They endure. And in doing so, they show us what resilience really means.

The Future of Bone Health

Science continues to advance. Researchers are developing new medications with fewer side effects and greater effectiveness. Genetic testing may one day predict osteoporosis risk before bone is ever lost. Bioengineered scaffolds could help regrow damaged bone. And digital health tools—apps, wearables, telemedicine—are bringing bone care into the hands of patients in real time.

Preventative medicine is the future. Educating children and young adults about bone health—especially during the critical bone-building years of adolescence—can change the course of a lifetime. Schools, doctors, families—all have roles to play in building a culture that values the invisible architecture beneath our skin.

Osteoporosis may never fully disappear. But its impact can be softened. Its silence can be broken. And those living with it can be empowered.

In the End, We Are All Bone

Beneath our differences—age, race, gender, class—we are all made of the same fundamental structure: bone. It is our first framework, forming in the womb. It carries us through childhood, youth, and into the fragile poetry of old age. When we touch someone’s hand, we are only ever a few millimeters from their skeleton.

Caring for our bones is an act of reverence—for life, for movement, for freedom. And understanding osteoporosis is not about fear—it’s about hope. The hope that through knowledge, compassion, and science, we can live not just longer lives, but fuller ones.

So let us listen to our bones. Let us honor their silent labor. And let us remember: even the most fragile body can contain unimaginable strength.