Imagine walking through the front door of your childhood home. You can feel the texture of the doorknob, hear the faint creak of the hinges, see the light spilling through the window just the way it used to. You step inside, and every detail feels so vivid you could reach out and touch it. This is not just nostalgia — it’s a neurological superpower you’ve been carrying your whole life. It is also the beating heart of the Memory Palace Method, a mnemonic technique that transforms spaces we know into landscapes for knowledge.

The human brain has always had an intimate relationship with place. Our ancestors were wanderers, hunters, navigators. Their survival depended on remembering the location of water, shelter, and danger. Over tens of thousands of years, our neural architecture evolved to excel at spatial memory. When we remember a place, we don’t just store a flat map in our minds — we store sensations, sounds, and emotions, creating a rich three-dimensional experience that can be recalled with remarkable clarity.

The Memory Palace Method, also called the method of loci, taps directly into this ancient capability. It allows us to anchor abstract information — dates, facts, names, speeches — to vivid mental locations. And in doing so, it turns memory from a brittle list into a living environment.

From Ancient Orators to Competitive Memory Athletes

The method’s roots reach back more than two thousand years. The story begins with the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos, who, according to legend, attended a banquet in Thessaly. Shortly after he stepped outside, the roof of the banquet hall collapsed, killing everyone inside. The bodies were unrecognizable, but Simonides was able to identify each victim by recalling exactly where they had been seated. In that moment, he realized that by mentally placing things — or people — in specific locations, he could recall them with perfect accuracy.

Greek and Roman orators soon adopted the method as a core tool for delivering hours-long speeches without notes. Cicero described walking through an imagined building, with each room containing a symbolic image tied to a specific part of his speech. The more absurd or emotionally charged the images, the more easily they stuck. In an age without smartphones, notepads, or teleprompters, the Memory Palace was a technology of the mind — portable, infinite, and free.

Fast forward to the present, and the technique is still alive. Modern “memory athletes” use it to memorize decks of cards in under 30 seconds, strings of hundreds of random numbers, or the order of thousands of historical events. But what was once an art now has a scientific explanation.

How the Brain Builds Palaces

At the core of the Memory Palace’s effectiveness is the hippocampus, a seahorse-shaped structure buried deep within the temporal lobe. The hippocampus plays a central role in both spatial navigation and episodic memory — the recollection of specific events, places, and times. Neuroscientists discovered this link in part through studies of London taxi drivers, whose training requires memorizing the city’s complex street layout, known as “The Knowledge.” Brain scans revealed that these drivers had enlarged posterior hippocampi compared to the average person.

When you construct a Memory Palace, you are essentially hacking this neural machinery. You take advantage of the hippocampus’s natural ability to encode space, then attach unrelated information to those spatial cues. Each “location” in the palace becomes a neural hook on which to hang a memory.

But the hippocampus doesn’t work alone. The parahippocampal place area helps process the identity of specific locations. The retrosplenial cortex assists in navigating between them. Meanwhile, the visual association areas of the brain process the imagery you create, especially if it’s unusual, vivid, or bizarre. Emotional regions such as the amygdala enhance the encoding if the image triggers strong feelings — even if those feelings are surprise, amusement, or mild discomfort.

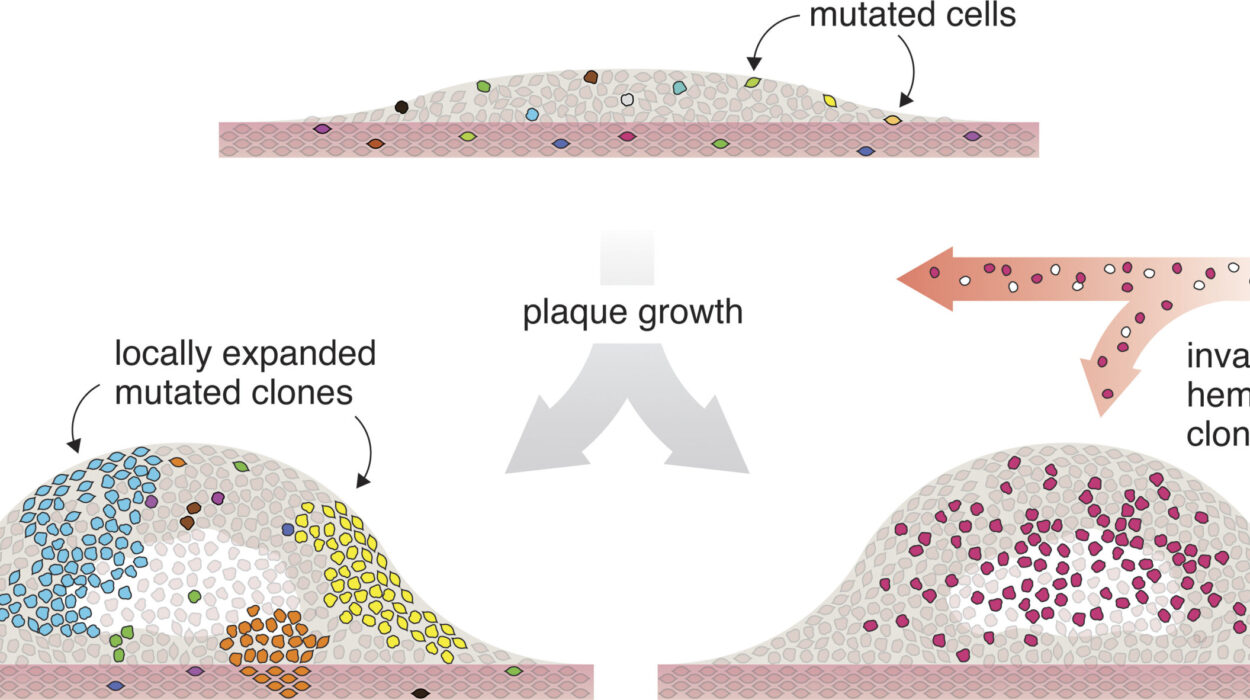

This integration of space, imagery, and emotion creates what cognitive scientists call elaborative encoding — the process of making information richer, more connected, and therefore more retrievable.

The Art of Imagination

A Memory Palace is not just a mental blueprint of a real place. The secret to its power lies in how you decorate it with images that are impossible to forget. Suppose you want to remember that the capital of France is Paris. Instead of simply picturing the Eiffel Tower in your living room, imagine a twenty-foot-tall Eiffel Tower made of melting chocolate, dripping all over your carpet, while an accordion player serenades you from the couch. The more sensory details, the better. The stranger, the better.

This works because the human brain is terrible at remembering abstract data in isolation, but astonishingly good at remembering things that are emotional, sensory-rich, or out of the ordinary. Neuroscientists often refer to this as the von Restorff effect — the tendency for distinctive items to be remembered more easily than common ones.

By fusing the mundane (your living room) with the absurd (a melting Eiffel Tower), you create a mental image that’s hard to misplace. When you later “walk” through your Memory Palace, these absurdities act as luminous markers, guiding you from one piece of information to the next.

Memory as Navigation

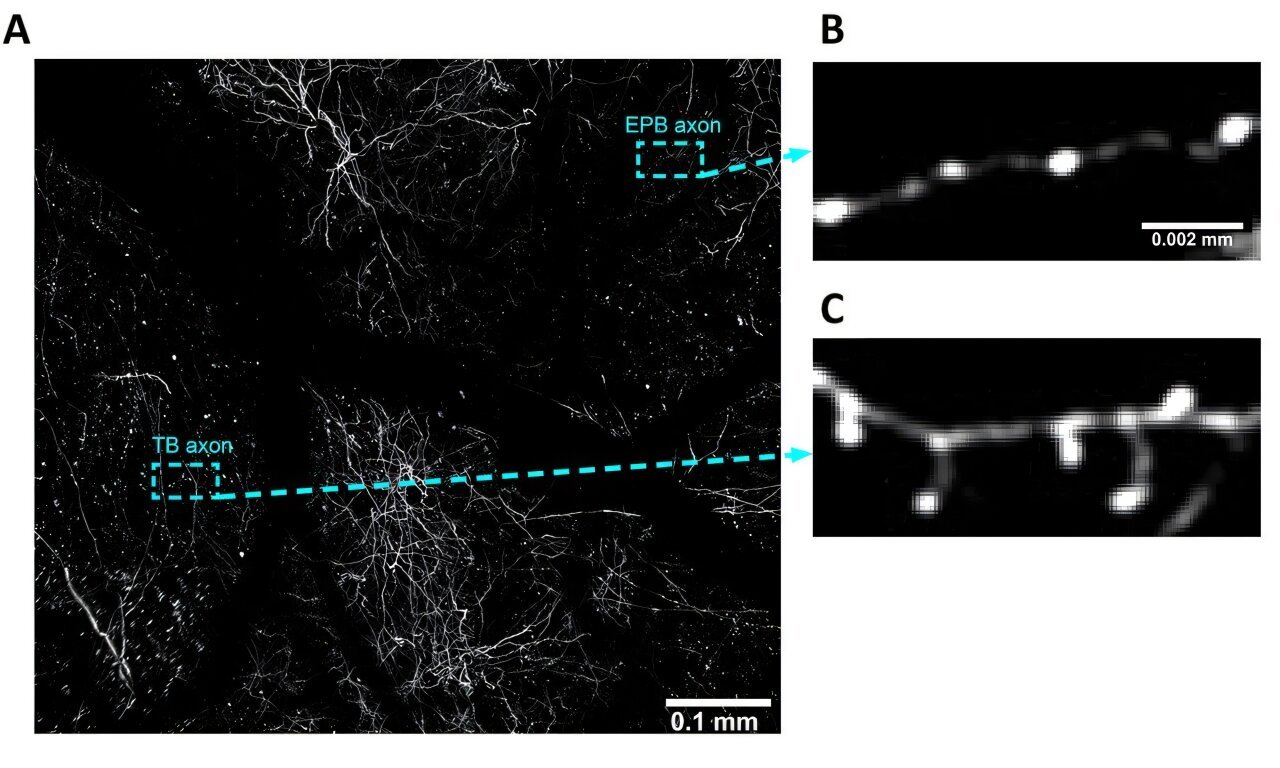

When you recall information from a Memory Palace, you are essentially taking a mental journey. This act of “walking” from room to room or landmark to landmark engages the brain’s navigation system — the same one that would guide you through a physical environment. Neurons called place cells in the hippocampus fire when you imagine yourself in specific locations. Meanwhile, grid cells in the entorhinal cortex create an internal coordinate system, allowing you to move through your palace in a consistent order.

This is one reason why the method can store enormous quantities of information without confusion. Each memory has a specific “address” in the palace. Just as you can’t accidentally walk into two rooms at once in real life, you won’t confuse the memories stored in distinct palace locations.

The Neurological Advantage

From a neurological perspective, the Memory Palace leverages three key mechanisms:

- Dual coding — storing information in both visual-spatial and verbal form.

- Contextual retrieval — embedding data in a rich, interconnected environment.

- Emotional tagging — using surprising, funny, or strange imagery to recruit the amygdala and boost retention.

Functional MRI studies show that when skilled mnemonists use the method, their brains display heightened activity not only in memory-related areas but also in the visual cortex and parietal regions associated with spatial reasoning. This distributed activation pattern helps strengthen the memory trace, making it more resistant to forgetting.

Beyond Parlor Tricks

For all its use in competitions, the Memory Palace is far from a party trick. Students use it to memorize entire textbooks. Actors use it to retain lines. Medical professionals use it to remember complex anatomical structures. Polyglots use it to store vocabulary in multiple languages. The method is so adaptable because it works with the brain’s natural strengths rather than against them.

Even in patients with early-stage memory decline, training in spatial mnemonics can improve recall performance. This suggests that while certain aspects of memory degrade with age, the spatial systems in the brain remain relatively robust.

The Limits and Misconceptions

Yet the Memory Palace is not magic. It requires time to build and practice to use efficiently. While it’s unmatched for ordered recall, it’s less efficient for rapidly updating information. For example, if you store a to-do list in a palace but change the list daily, you’ll spend energy remodeling your mental architecture. Additionally, the method does not make you understand a concept — it only helps you remember it. Understanding requires a different layer of cognitive processing.

Some also assume that using mnemonics is “cheating” the mind’s natural memory. In truth, it’s the opposite. The method works precisely because it aligns with the deep evolutionary wiring of our species.

Building Your First Palace: A Neurological Perspective

When constructing your first Memory Palace, neuroscientists would advise starting with a place you know intimately — your home, your school, a favorite walking route. Familiarity frees cognitive resources for the imagery itself. As you select locations within the palace, try to choose ones with clear boundaries: a door, a hallway, a desk, a window. Each should serve as a distinct container for an image.

When you encode, engage as many sensory modalities as possible: sight, sound, smell, texture, even temperature. This multi-sensory engagement recruits multiple cortical regions, creating a denser network of retrieval cues.

The Memory Palace in Modern Life

In our age of constant digital reminders, it’s tempting to outsource memory entirely. But cognitive scientists warn that over-reliance on external storage — what’s sometimes called “digital amnesia” — can weaken our natural recall. The Memory Palace offers a counterbalance: a way to keep the brain’s spatial and visual systems active, to feel the satisfying click of retrieving information from within, rather than summoning it from a screen.

Even beyond practical applications, there’s a joy in the method. To build a Memory Palace is to explore an inner landscape that is uniquely yours, populated by surreal scenes of your own invention. It turns learning into a creative act, and recall into a kind of mental travel.

Memory as an Act of Art

In the end, the Memory Palace is more than a mnemonic. It is a reminder that memory is not a filing cabinet, but a living architecture — one that blends reason with imagination, fact with fantasy. Every palace you build is an artifact of your mind’s flexibility, a proof that you can shape thought as tangibly as a sculptor shapes clay.

Neuroscience explains how it works, but the experience of using it — of strolling through a hall in your mind and finding, in some impossible corner, exactly the thing you need — belongs to the realm of art.