The esophagus is a remarkable organ—an elegant, muscular tube that quietly carries food and liquid from the mouth to the stomach. We rarely think about it, unless we feel heartburn after a heavy meal or a lump in the throat during times of stress. Yet this seemingly simple passageway can become the site of one of the most aggressive and deadly cancers known to medicine: esophageal cancer.

Unlike some cancers that give early warnings, esophageal cancer often creeps into a person’s life silently. By the time symptoms are noticed—trouble swallowing, unexplained weight loss, or chest discomfort—the disease may already be advanced. For patients and their families, the diagnosis often comes as a devastating shock. And yet, behind the clinical statistics and medical terminology lies a human story: of courage, of struggle, and increasingly, of hope, as science pushes forward with better treatments and earlier detection methods.

This article dives deeply into esophageal cancer: its causes, symptoms, methods of diagnosis, and the wide range of treatments available today. Along the way, we’ll explore the science, the human experience, and the evolving future of how this disease is understood and managed.

What Is Esophageal Cancer?

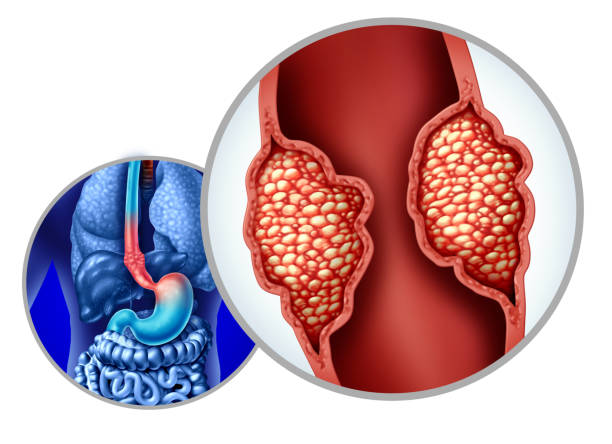

Esophageal cancer is a malignant tumor that develops in the lining of the esophagus. It occurs when cells in the esophagus begin to grow uncontrollably, forming a mass that can obstruct the passage of food and spread to other parts of the body.

The esophagus itself is about 25 centimeters long in adults, running behind the trachea and in front of the spine, connecting the throat to the stomach. Its lining is normally protected from damage by a layer of specialized cells, but under certain conditions—such as chronic irritation from acid reflux, smoking, or alcohol use—these cells can change, mutate, and eventually turn cancerous.

Globally, esophageal cancer is the seventh most common cancer and the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths, according to the World Health Organization. Its incidence varies greatly by region, with particularly high rates in Asia and parts of Africa, while it remains less common in North America and Western Europe.

Types of Esophageal Cancer

Understanding the different types of esophageal cancer is critical because they arise from different cells, have different risk factors, and may respond differently to treatment.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

This type originates from the flat, thin cells that line the surface of the esophagus. It typically occurs in the upper and middle parts of the esophagus. Squamous cell carcinoma has been strongly linked to smoking, heavy alcohol use, and dietary deficiencies. In regions such as China, Iran, and South Africa, this type has historically been the most common form.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma begins in glandular cells, usually in the lower esophagus near the junction with the stomach. It has become the predominant type in Western countries, largely due to the rising prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett’s esophagus, a condition in which chronic acid reflux changes the lining of the esophagus into a precancerous state. Obesity, which increases reflux, is another significant factor fueling adenocarcinoma rates.

Causes and Risk Factors

Esophageal cancer does not arise from a single cause. Instead, it develops from a complex interplay of genetic predispositions, lifestyle choices, and environmental exposures.

Lifestyle-Related Causes

- Tobacco use: Smoking or chewing tobacco exposes the esophagus to carcinogens, increasing the risk dramatically.

- Alcohol consumption: Heavy drinking damages the lining of the esophagus, particularly when combined with smoking.

- Dietary habits: Diets low in fruits, vegetables, and certain vitamins have been associated with higher risk, while hot beverages consumed at very high temperatures may also cause chronic irritation.

Medical Conditions

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): Persistent acid reflux damages the esophagus and can lead to Barrett’s esophagus, a recognized precancerous condition.

- Barrett’s Esophagus: In Barrett’s, normal squamous cells are replaced by glandular cells more typical of the stomach or intestine. These cells have a higher likelihood of becoming cancerous.

- Achalasia: A rare disorder where the esophagus fails to move food into the stomach, leading to chronic stasis and irritation.

- Head and neck cancers: Individuals with these cancers have a higher likelihood of developing esophageal cancer as well.

Genetic and Environmental Factors

Genetics plays a smaller but notable role. Some inherited syndromes, such as tylosis (a rare disorder causing thickened skin on the palms and soles), greatly increase the risk. Environmental exposures, such as nitrosamines from preserved foods or exposure to certain pollutants, also contribute.

Symptoms: When the Body Speaks

One of the great challenges of esophageal cancer is that early stages often cause no symptoms. As the tumor grows, it begins to interfere with the normal function of the esophagus.

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia): This is the hallmark symptom, usually starting with difficulty swallowing solid foods and progressing to problems with liquids.

- Unintentional weight loss: Because eating becomes painful or difficult, patients often lose weight rapidly.

- Chest pain or discomfort: Pain may occur behind the breastbone, sometimes mistaken for heartburn.

- Persistent cough or hoarseness: If the tumor affects nerves or the trachea.

- Vomiting or regurgitation of food: Particularly when the esophagus becomes significantly narrowed.

- Bleeding: In some cases, tumors can cause bleeding into the esophagus, leading to black stools or vomiting blood.

These symptoms often appear late, which is why early diagnosis is so difficult. Many patients ignore them, attributing them to acid reflux, dietary habits, or aging.

Diagnosis: How Doctors Detect Esophageal Cancer

Once symptoms raise suspicion, a series of tests can be performed to confirm diagnosis and determine the stage of the disease.

Endoscopy

An endoscope—a thin, flexible tube with a camera—is passed down the throat, allowing doctors to visually inspect the esophagus. Abnormal areas can be biopsied to confirm cancer under a microscope.

Imaging Tests

- CT scans and MRI: Provide detailed images of the chest and abdomen to see how far the cancer has spread.

- PET scans: Detect areas of increased metabolic activity, useful for identifying metastases.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): Combines endoscopy with sound waves to create detailed images of the esophageal wall and nearby lymph nodes.

Staging

Staging describes how advanced the cancer is:

- Stage I: Tumor confined to the lining of the esophagus.

- Stage II: Cancer has invaded deeper layers or nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage III: Cancer has spread through the esophageal wall and more lymph nodes.

- Stage IV: Cancer has spread to distant organs, such as the liver or lungs.

Accurate staging is crucial for selecting the most effective treatment.

Treatment Options

Treatment for esophageal cancer depends on the stage at diagnosis, the patient’s overall health, and the type of cancer.

Surgery

Surgery remains a cornerstone of treatment for localized disease. The most common procedure is esophagectomy, where part or all of the esophagus is removed and replaced with a section of the stomach or intestine. This is a complex operation with risks, but for many patients, it offers the best chance of cure.

Radiation Therapy

High-energy beams are used to kill cancer cells or shrink tumors. Radiation may be used before surgery to make tumors operable (neoadjuvant therapy), after surgery to reduce recurrence (adjuvant therapy), or as palliative care to relieve symptoms.

Chemotherapy

Drugs such as cisplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and paclitaxel are used to kill rapidly dividing cancer cells. Chemotherapy can be given alone, with radiation (chemoradiation), or before and after surgery.

Targeted Therapy

Advances in molecular biology have identified drugs that target specific pathways in cancer cells. For example, trastuzumab (Herceptin) may be used for tumors overexpressing the HER2 protein.

Immunotherapy

Checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab and nivolumab have revolutionized treatment for certain patients with advanced esophageal cancer. By enhancing the body’s own immune response, they offer new hope for long-term control in cases where traditional treatments fail.

Palliative Care

For advanced cancer, treatment may focus on improving quality of life. This may include stents to keep the esophagus open, nutritional support, and medications to control pain and symptoms.

Living With Esophageal Cancer

Beyond medical treatments, esophageal cancer profoundly affects daily life. Patients often need to adapt to new ways of eating—smaller, more frequent meals, softer foods, or even liquid nutrition. Emotional challenges are equally significant, as patients grapple with uncertainty, fear, and physical changes.

Support from family, friends, healthcare providers, and cancer support groups becomes vital. Psychological counseling, nutritional advice, and palliative care specialists play important roles in helping patients maintain dignity and hope.

Prevention: Reducing the Risk

While not all cases can be prevented, several lifestyle changes reduce the risk:

- Avoiding tobacco in all forms.

- Limiting alcohol consumption.

- Maintaining a healthy weight.

- Eating a diet rich in fruits and vegetables.

- Managing GERD effectively to prevent progression to Barrett’s esophagus.

- Regular screening for high-risk individuals, particularly those with Barrett’s esophagus.

The Future of Esophageal Cancer Care

Research is rapidly advancing, with scientists exploring genetic markers, liquid biopsies, and artificial intelligence to detect cancer earlier. Personalized medicine—where treatments are tailored to the genetic profile of a tumor—is becoming a reality. Immunotherapy is opening new doors, offering durable responses for some patients who previously had few options.

One day, esophageal cancer may no longer be the deadly disease it is today. With greater awareness, early detection, and the continued progress of science, survival rates can improve, and patients can live longer, fuller lives.

Conclusion: Hope Amidst the Challenge

Esophageal cancer remains one of the most formidable cancers, striking silently and progressing swiftly. Yet within this challenge lies hope: hope in the growing arsenal of treatments, in the dedication of researchers, and in the resilience of patients who face the disease with courage.

Understanding its causes, recognizing its symptoms, and pursuing early diagnosis are the first steps toward saving lives. For those already facing it, advances in surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy are transforming the outlook. And for society at large, prevention and awareness remain powerful tools.

Health, after all, is not just about fighting disease but about living fully. In the fight against esophageal cancer, every step forward—whether in the lab, the clinic, or the community—brings us closer to a future where this silent disease no longer steals voices, meals, and lives.