For centuries, gold has symbolized desire, power, and permanence. It has fueled empires, driven exploration across oceans, and shaped human history in ways few materials ever have. Now, in an age when Earth itself feels increasingly small, a new and astonishing idea has entered serious scientific and economic discussion: what if the greatest gold rush in history does not happen on Earth at all, but in space? What if the next frontier of wealth lies not buried beneath mountains or riverbeds, but drifting silently between planets?

Asteroid mining, once confined to the pages of science fiction, is now a topic of genuine scientific research, engineering debate, and economic speculation. At its heart lies a bold question that blends human ambition with cosmic reality: can we mine asteroids for gold, and if we can, what would that mean for the future of the space economy and for life on Earth?

This question is not only about technology or money. It is about how humanity sees its future, how it treats its home planet, and how far it is willing to extend its reach into the universe.

The Allure of Asteroids

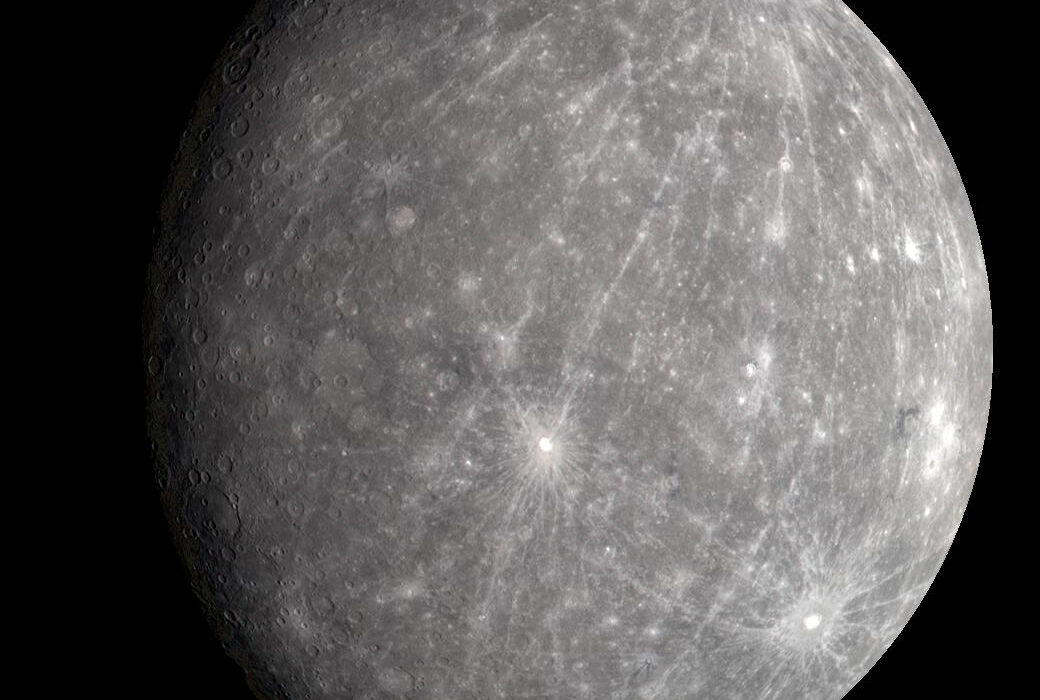

Asteroids are remnants of the early solar system, rocky and metallic fragments left over from planetary formation. They orbit the Sun in vast numbers, ranging in size from tiny pebbles to objects hundreds of kilometers across. Some remain clustered in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, while others wander closer to Earth, passing through near-Earth space on predictable paths.

What makes asteroids so alluring is not just their abundance, but their composition. Many asteroids are rich in metals that are rare or difficult to extract on Earth. Some contain iron and nickel in high concentrations. Others carry platinum-group metals, including platinum, palladium, and gold. These elements formed in ancient stellar explosions long before the Sun existed, and they are scattered throughout the solar system like cosmic treasure.

On Earth, gold is rare because most of it sank into the planet’s core during its early molten phase. The gold we mine today largely arrived later, delivered by asteroid impacts billions of years ago. In a very real sense, every gold ring or coin on Earth is a fragment of ancient space. Asteroid mining, then, would not be creating a new source of gold so much as returning to its original home.

Gold in Space: Myth and Reality

The idea that asteroids contain enormous quantities of gold often captures the imagination, sometimes exaggerated into visions of instant trillionaires and collapsing global markets. While it is true that some metallic asteroids contain significant amounts of precious metals, the reality is more nuanced and far more complex.

Not all asteroids are rich in gold. Many are composed primarily of silicate rock, similar to Earth’s crust. Others are carbon-rich, containing organic compounds and water rather than metals. Even among metallic asteroids, gold is typically present in small concentrations mixed with other elements. Extracting it is not as simple as scooping up nuggets floating in space.

Yet even low concentrations can matter. An asteroid a few hundred meters wide could contain more platinum-group metals than have ever been mined on Earth. The sheer scale of space changes the economics entirely. What seems rare on Earth can be relatively abundant in the solar system as a whole.

The challenge is not whether gold exists in asteroids, but whether it can be accessed, extracted, and used in a way that makes sense scientifically, economically, and ethically.

The Physics of Reaching an Asteroid

Before any mining can begin, humanity must reach the asteroids themselves. This is not trivial. Space is vast, and moving objects and equipment across it requires energy, precision, and time.

Asteroids are not stationary targets. They orbit the Sun at high speeds, following paths influenced by gravity and subtle forces like solar radiation. Reaching one requires careful planning, precise navigation, and propulsion systems capable of long-duration missions. Unlike the Moon or Mars, asteroids have extremely weak gravity, which complicates landing, anchoring, and excavation.

Yet physics also offers advantages. Many near-Earth asteroids require less energy to reach than the surface of the Moon. Once there, the lack of strong gravity means that lifting material off the asteroid requires far less energy than lifting material from Earth. In theory, this makes space-based mining more efficient once the initial technological hurdles are overcome.

The physics of orbital mechanics turns space into a complex but navigable landscape, where energy costs depend more on trajectories and timing than on distance alone.

Mining Without Gravity

Mining on Earth relies on gravity in ways we often take for granted. Rocks fall downward. Dust settles. Heavy machinery presses into the ground. None of this works the same way on an asteroid.

In microgravity, breaking rock can send fragments drifting away into space. Traditional digging methods become useless. Engineers must rethink the very concept of mining, designing systems that can grip, cut, and contain material without relying on weight.

Some proposed methods involve enclosing portions of an asteroid within sealed structures and processing material inside. Others suggest using controlled heating to release metals or volatiles. Magnetic separation could help extract metallic components. These ideas remain largely theoretical, but they are grounded in known physical principles.

The absence of gravity is not merely an obstacle. It also allows new approaches impossible on Earth. Material can be moved with minimal energy. Structures do not need to support their own weight. The physics of space opens possibilities as strange as they are promising.

Gold Versus Water: What Is Truly Valuable in Space

When discussing asteroid mining, gold often dominates the conversation because of its cultural and economic symbolism. Yet from a space-based perspective, gold may not be the most valuable resource at all.

Water is arguably the true currency of space. It can support human life, shield against radiation, and be split into hydrogen and oxygen for rocket fuel. Asteroids rich in water could serve as refueling stations, enabling deeper exploration of the solar system.

Metals like iron and nickel could be used to build structures in space, reducing the need to launch heavy materials from Earth. Platinum-group metals have critical industrial uses, particularly in electronics and catalysis.

Gold, while valuable on Earth, may play a smaller role in early space economies. Its significance lies not only in its intrinsic properties but in its potential impact on Earth-based markets. This tension between space value and Earth value lies at the heart of the asteroid mining debate.

The Economics of Bringing Gold Home

Suppose we develop the technology to mine gold from asteroids. Should we bring it back to Earth? This question exposes the fragile balance between abundance and value.

Gold’s worth depends on its scarcity. If asteroid mining suddenly floods Earth with gold, its price could collapse. This would disrupt economies, undermine industries, and challenge financial systems built on assumptions of rarity. In such a scenario, asteroid gold could paradoxically become less valuable than the cost of retrieving it.

For asteroid mining to make economic sense, the flow of materials to Earth would need to be carefully managed. Alternatively, space-mined resources might primarily be used in space, supporting infrastructure, manufacturing, and exploration beyond Earth.

The future space economy may not mirror Earth’s economy. Value in space is defined by utility, energy costs, and survival rather than tradition or symbolism.

Legal and Ethical Frontiers

Mining asteroids raises profound legal and ethical questions. Space is governed by international agreements that emphasize peaceful use and prohibit national ownership of celestial bodies. Yet these agreements were written before asteroid mining became a serious possibility.

Who owns an asteroid? Who has the right to extract its resources? How are benefits shared, and who bears responsibility for potential harm? These questions have no simple answers.

There is also the ethical question of exploitation. Humanity’s history of resource extraction on Earth is filled with environmental damage and inequality. As we extend our reach into space, there is an opportunity to learn from past mistakes, but also a risk of repeating them on a cosmic scale.

Asteroid mining forces humanity to confront what kind of spacefaring civilization it wants to become.

Technology as the True Limiting Factor

The greatest obstacle to asteroid mining is not physics or legality, but technology. We need reliable, autonomous systems capable of operating for years in deep space. We need advanced robotics, artificial intelligence, and materials that can withstand radiation, temperature extremes, and mechanical stress.

Communication delays mean that mining operations must function with minimal human intervention. Machines must make decisions, adapt to unexpected conditions, and repair themselves when possible.

Developing such technology is expensive and slow, but it has benefits beyond mining. Advances in robotics, energy systems, and space engineering could transform exploration, science, and even life on Earth.

Asteroid mining is less a single goal than a catalyst for broader technological evolution.

The Emotional Power of the Gold Rush

The idea of mining asteroids taps into something deeply human. It echoes the great gold rushes of history, moments when the promise of wealth drew people into unknown lands. It speaks to ambition, risk, and hope.

But unlike historical gold rushes, this one is not driven by individuals with picks and pans. It is driven by engineers, scientists, and long-term vision. The risks are higher, the timescales longer, and the rewards more uncertain.

There is a quiet poetry in the idea of reaching into space to reclaim fragments of ancient stars. It reminds us that humanity’s story is not confined to Earth, that our curiosity naturally extends outward.

Environmental Implications for Earth

One of the most compelling arguments for asteroid mining is environmental. Mining on Earth often causes severe ecological damage, polluting water, destroying habitats, and contributing to climate change. If certain resources could be obtained from space instead, the pressure on Earth’s ecosystems might be reduced.

This does not mean asteroid mining is environmentally neutral. Launches consume energy, and space operations have their own impacts. Yet compared to the long-term damage of terrestrial mining, space-based extraction could offer a cleaner alternative.

The future space economy may be driven as much by the desire to protect Earth as by the pursuit of profit.

Asteroids and the Expansion of Human Civilization

Asteroid mining is not just about resources. It is about presence. Establishing operations on asteroids would mark a significant step in humanity’s expansion beyond Earth.

Such operations could support space habitats, research stations, and deep-space missions. They could make human activity in space more sustainable and less dependent on Earth.

In this vision, asteroids become stepping stones rather than destinations, part of a larger network of human activity across the solar system.

Scientific Knowledge as a Hidden Treasure

Even if asteroid mining never becomes economically dominant, the scientific knowledge gained along the way would be invaluable. Studying asteroids up close reveals clues about the formation of planets, the origins of water and organic molecules, and the early history of the solar system.

Mining missions would require detailed analysis of asteroid composition and structure, advancing planetary science. In this sense, the pursuit of gold becomes a pursuit of understanding.

Science and commerce, often seen as opposing forces, may find unexpected harmony in space.

Risks and Uncertainties

Asteroid mining carries significant risks. Technical failures, economic miscalculations, and unforeseen challenges could derail projects. There is also the risk of creating space debris or altering asteroid trajectories, potentially endangering Earth.

Careful planning, international cooperation, and scientific oversight are essential. The stakes are high, not only financially but existentially.

These risks serve as a reminder that space is not a lawless frontier, but a shared environment requiring responsibility and foresight.

The Timeline of Possibility

Asteroid mining is unlikely to become commonplace in the immediate future. The technological and economic barriers remain substantial. Yet progress is incremental. Small missions test key technologies. Robotic explorers gather data. Private and public institutions invest in long-term research.

The future space economy will not arrive suddenly. It will emerge gradually, shaped by successes and failures, driven by persistence rather than hype.

Gold may not be the first resource mined, nor the most important. But its symbolism ensures that it remains central to the conversation.

Rethinking Wealth in a Cosmic Context

Asteroid mining challenges traditional ideas of wealth. When resources are no longer bound to a single planet, scarcity takes on a new meaning. Value becomes relative, shaped by location, need, and energy costs.

In space, wealth may be measured not in gold, but in access, sustainability, and knowledge. The true riches of asteroid mining may lie in enabling humanity to survive and thrive beyond Earth.

This shift in perspective may be one of the most profound consequences of expanding into space.

A Future Written in the Stars

Can we mine asteroids for gold? Scientifically, the answer is yes. The laws of physics allow it. The materials exist. The challenges are immense but not insurmountable.

Whether we should, and how we will, remains an open question shaped by economics, ethics, and vision. The future space economy will reflect humanity’s choices, values, and willingness to think beyond immediate gain.

Asteroid mining is not merely about extracting metal from rock. It is about redefining humanity’s relationship with the universe. It asks whether we will carry our old habits into space, or whether we will evolve alongside our expanding reach.

Gold has always been a mirror for human desire. In the silent drift of asteroids, far from Earth’s noise and conflict, that mirror now reflects a larger question: not how much we can take from the universe, but how wisely we can become a part of it.