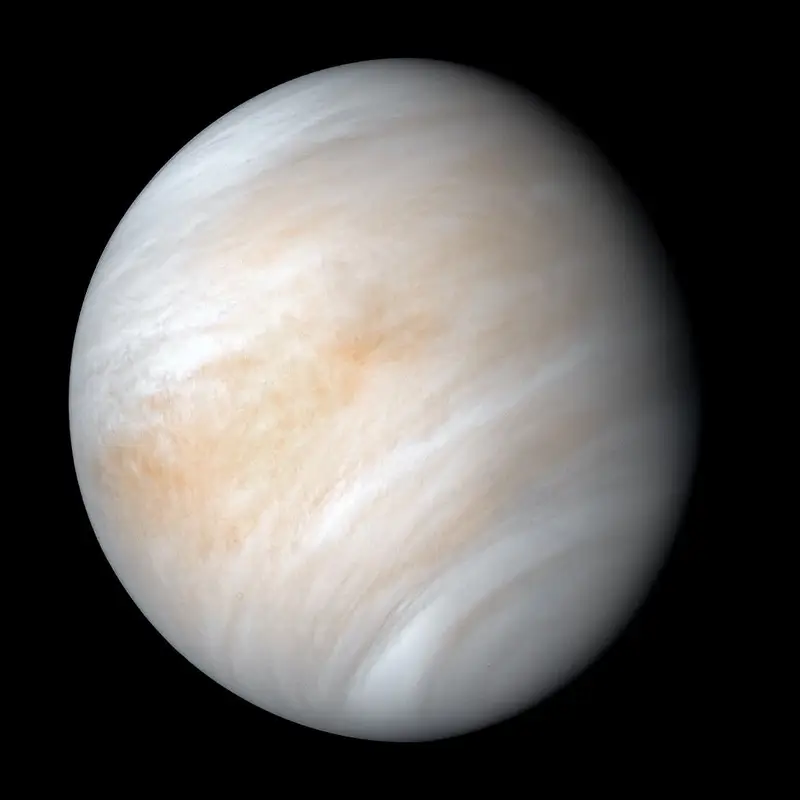

Venus begins as a paradox. From afar, it appears almost Earth-like in size, mass, and composition, a sister planet formed from similar materials in the same region of the young Solar System. Yet beneath its brilliant clouds lies a surface hot enough to melt lead, crush spacecraft, and erase nearly every trace of its ancient past. Venus is not merely warm; it is catastrophically hot, with surface temperatures averaging around 465 degrees Celsius, hotter than Mercury despite Venus being much farther from the Sun. Understanding why Venus is so hot requires more than a simple explanation of proximity to sunlight. It demands a deep exploration of atmospheric physics, planetary evolution, and a phenomenon known as the runaway greenhouse effect.

The story of Venus is not only about a planet gone wrong. It is also a story about how delicate planetary climates can be, how small differences can amplify over time, and how physics governs the fate of worlds. In unraveling why Venus became an inferno, scientists have uncovered insights that extend far beyond one planet, shedding light on Earth’s climate, the habitability of exoplanets, and the fragile balance that allows life to exist at all.

The Greenhouse Effect: A Necessary Beginning

To understand the runaway greenhouse effect, one must first understand the greenhouse effect itself, which is neither inherently dangerous nor unusual. The greenhouse effect is a fundamental physical process by which a planet’s atmosphere traps some of the heat it receives from its star. Sunlight reaches the surface, warming it, and the surface then emits infrared radiation back toward space. Certain atmospheric gases, such as carbon dioxide and water vapor, absorb and re-emit this infrared radiation, preventing all of the heat from escaping. The result is a warmer surface temperature than the planet would have without an atmosphere.

On Earth, this process is essential. Without a natural greenhouse effect, Earth’s average surface temperature would be far below freezing, rendering the planet inhospitable to liquid water and life as we know it. The greenhouse effect, in moderation, is not a flaw but a feature of planetary climate systems. The problem arises when this effect becomes self-amplifying and uncontrollable, pushing a planet into a new and extreme thermal state.

Venus represents the most dramatic example of this process taken to its limit. Its atmosphere did not merely trap heat; it entered a feedback loop in which warming caused further warming, escalating until the planet became permanently locked in a superheated condition.

Venus’s Atmosphere: Thick, Heavy, and Relentless

The defining feature of Venus is its atmosphere. Composed of more than 96 percent carbon dioxide, it is extraordinarily dense, exerting a surface pressure about 92 times greater than Earth’s. Standing on the surface of Venus would be equivalent to standing nearly one kilometer underwater on Earth, with the additional burden of searing heat.

Carbon dioxide is a highly effective greenhouse gas because it absorbs infrared radiation over a wide range of wavelengths. The sheer quantity of carbon dioxide in Venus’s atmosphere ensures that heat escaping from the surface is repeatedly absorbed and re-emitted, trapping energy close to the ground. This process alone would make Venus warm, but it does not fully explain the extreme temperatures observed.

The atmosphere also contains thick clouds of sulfuric acid that reflect much of the incoming sunlight back into space. Paradoxically, despite reflecting more sunlight than Earth, Venus remains far hotter. This illustrates a crucial point: Venus’s temperature is not driven primarily by how much sunlight it absorbs, but by how effectively its atmosphere prevents heat from escaping.

The Early Venus: A Planet at a Crossroads

Venus was not always the hellish world we see today. Early in its history, Venus likely had conditions not entirely unlike those of early Earth. Models of planetary formation suggest that Venus may have possessed significant amounts of water, possibly even shallow oceans. The Sun itself was fainter in its youth, meaning Venus received less energy than it does today.

The key difference between Venus and Earth lies in their starting positions relative to the Sun. Venus orbits closer, receiving roughly twice as much solar energy as Earth. This difference, while seemingly modest on cosmic scales, placed Venus dangerously close to a climatic threshold.

As the young Sun gradually brightened, Venus warmed. Higher temperatures increased the evaporation of surface water, adding water vapor to the atmosphere. Water vapor is itself a powerful greenhouse gas, more effective molecule-for-molecule than carbon dioxide. This created a positive feedback loop: warming caused more evaporation, which caused more warming, which caused even more evaporation.

At some point, this feedback became unstoppable.

The Onset of the Runaway Greenhouse Effect

The runaway greenhouse effect occurs when a planet’s atmosphere becomes so rich in greenhouse gases that it can no longer effectively radiate heat into space. As surface temperatures rise, more water vapor enters the atmosphere, increasing its opacity to infrared radiation. Eventually, the outgoing heat reaches a maximum limit, beyond which additional surface warming does not increase heat loss to space.

When this limit is exceeded, the planet experiences runaway heating. Temperatures climb rapidly until all surface water evaporates, transforming oceans into thick atmospheric steam. This steam further amplifies the greenhouse effect, driving temperatures even higher.

On Venus, this process likely unfolded over millions of years. As water vapor accumulated in the upper atmosphere, it became vulnerable to ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. High-energy photons broke water molecules apart into hydrogen and oxygen. The lightweight hydrogen escaped into space, permanently depleting Venus of its water. The oxygen either reacted with surface rocks or was lost through other processes.

Once Venus lost its water, the planet lost a critical regulator of climate. On Earth, water plays a vital role in stabilizing temperature through cloud formation, precipitation, and chemical weathering. Venus, stripped of its oceans, was left with no mechanism to reverse its atmospheric heating.

Carbon Dioxide Without an Escape

On Earth, carbon dioxide is continuously cycled between the atmosphere, oceans, rocks, and living organisms. Rain dissolves carbon dioxide, forming weak acids that weather rocks. The resulting carbon compounds are carried into the oceans and eventually locked away in sediments. Plate tectonics then recycles some of this carbon back into the atmosphere through volcanic activity, maintaining a long-term balance.

Venus appears to lack this regulatory system. Without liquid water, chemical weathering could not proceed effectively. Without plate tectonics as we know them on Earth, carbon dioxide released by volcanic activity accumulated in the atmosphere instead of being sequestered in rocks.

Over time, Venus’s atmosphere became dominated by carbon dioxide, intensifying the greenhouse effect. Unlike Earth, Venus had no efficient way to remove this gas from the atmosphere. The planet’s climate crossed a point of no return, settling into a state of perpetual extreme heat.

Why Venus Is Hotter Than Mercury

One of the most striking aspects of Venus is that it is hotter than Mercury, even though Mercury orbits much closer to the Sun. Mercury lacks a substantial atmosphere, allowing heat absorbed during the day to radiate back into space at night. As a result, Mercury experiences extreme temperature swings, with scorching days and freezing nights.

Venus, by contrast, has an atmosphere so thick that it redistributes heat around the planet and traps it continuously. Day and night temperatures on Venus are nearly identical. The dense atmosphere acts as an insulating blanket, preventing heat from escaping and maintaining uniformly high temperatures.

This comparison highlights a crucial lesson in planetary physics. Atmospheric composition and structure can be more important than distance from a star in determining surface temperature. Venus is a testament to the power of atmospheric processes to dominate planetary climate.

The Physics of Heat Trapping on Venus

At the core of Venus’s extreme climate lies radiative transfer, the process by which energy moves through a medium via radiation. In Venus’s atmosphere, infrared radiation emitted by the surface is absorbed by greenhouse gases and re-emitted in all directions. A significant fraction of this re-emitted energy is directed back toward the surface, increasing its temperature.

As temperature rises, the surface emits more infrared radiation, but this additional energy is also absorbed by the atmosphere. The thick carbon dioxide layer ensures that radiation must be absorbed and re-emitted many times before escaping into space. Each interaction delays the escape of heat, effectively raising the planet’s equilibrium temperature.

The runaway greenhouse effect represents the extreme limit of this process, where the atmosphere becomes so opaque that further increases in surface temperature do not significantly increase outgoing radiation. Venus has reached this limit, locking the planet into a superheated state that persists regardless of daily or seasonal changes.

Clouds That Cool and Heat at the Same Time

Venus’s clouds add complexity to its climate. Composed primarily of sulfuric acid droplets, these clouds reflect a large fraction of incoming sunlight, giving Venus its bright appearance in the sky. This reflective property, known as high albedo, should in principle cool the planet.

However, the clouds also absorb infrared radiation emitted from below, contributing to the greenhouse effect. The net result is that Venus remains extremely hot despite reflecting much of the Sun’s energy. This dual role of clouds illustrates the subtle interplay between different atmospheric processes.

The sulfuric acid clouds themselves are a product of Venus’s harsh chemistry. Sulfur dioxide released by volcanic activity reacts with water vapor and sunlight in the upper atmosphere, forming sulfuric acid aerosols. These clouds are dynamic, constantly forming and dissipating, yet they persist as a stable feature of the planet’s climate.

A Slow Spin and a Long Day

Venus rotates extraordinarily slowly, with one Venusian day lasting longer than a Venusian year. This slow rotation influences atmospheric circulation and contributes to the planet’s uniform temperatures. Strong winds in the upper atmosphere circulate heat around the planet far more rapidly than the surface rotates, ensuring that no region cools significantly.

The slow rotation also affects how sunlight interacts with the atmosphere. Prolonged exposure to sunlight on one side of the planet could have intensified early heating, further driving the runaway greenhouse effect. While rotation alone does not explain Venus’s extreme heat, it plays a supporting role in shaping its climate dynamics.

Lessons for Earth’s Climate

Venus often serves as a cautionary example in discussions of climate change, but the comparison must be made carefully. Earth is not on the verge of becoming Venus. The differences in distance from the Sun, atmospheric composition, and the presence of oceans make a Venus-like runaway greenhouse extremely unlikely on Earth under foreseeable conditions.

However, Venus does demonstrate the power of greenhouse gases to reshape a planet’s climate over long timescales. It shows that positive feedback loops can amplify warming and that planetary climates can shift into entirely new regimes. Studying Venus helps scientists understand the boundaries of climate stability and the mechanisms that can push a planet beyond them.

Earth’s climate system includes stabilizing feedbacks, such as cloud formation and the carbon cycle, that Venus lacks. Preserving these stabilizing mechanisms is essential for maintaining a habitable climate. In this sense, Venus is not a prediction of Earth’s future but a reminder of how precious and delicate Earth’s climate balance is.

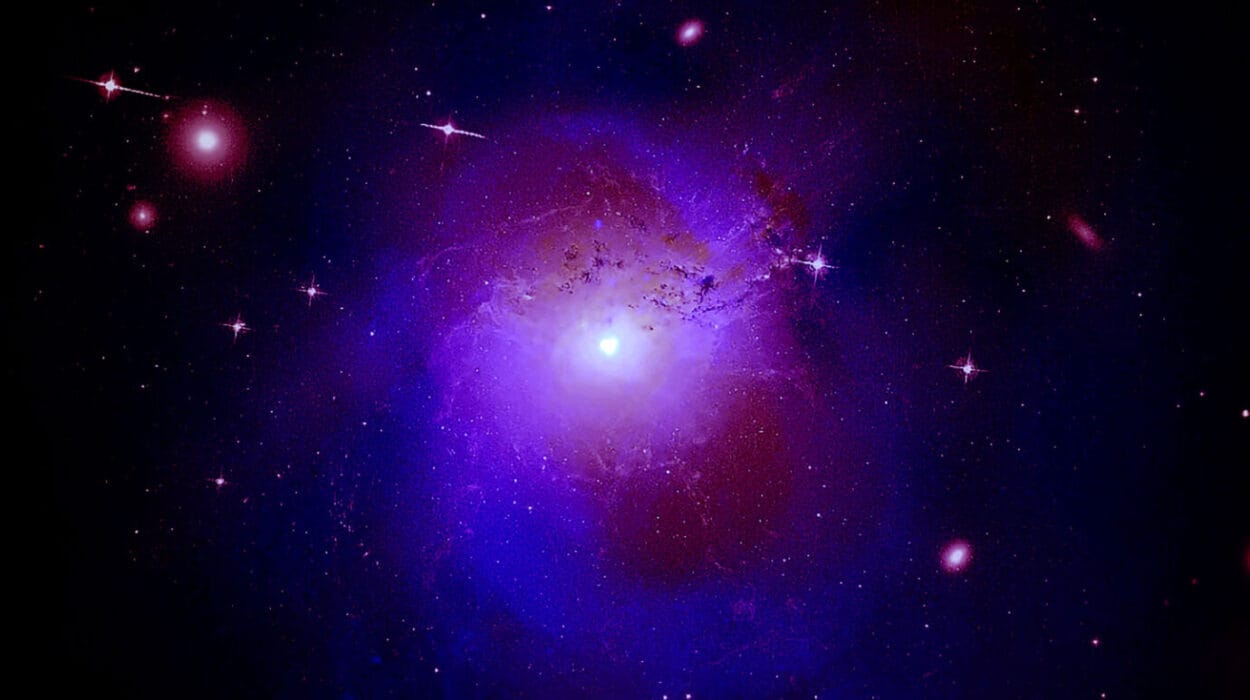

Venus and the Search for Habitable Worlds

The runaway greenhouse effect has profound implications for the search for life beyond Earth. Astronomers identify a region around stars known as the habitable zone, where temperatures could allow liquid water to exist on a planet’s surface. Venus likely formed near the inner edge of the Sun’s habitable zone, making it a critical case study.

Venus shows that being in or near the habitable zone does not guarantee habitability. Atmospheric composition, planetary mass, rotation, and geological activity all influence whether a planet can maintain stable conditions. Exoplanets similar in size to Earth but closer to their stars may be more Venus-like than Earth-like.

By studying Venus, scientists refine their understanding of which exoplanets are most likely to support life and which may have succumbed to runaway greenhouse conditions. Venus thus plays a central role in planetary science far beyond our Solar System.

A Planet Locked in Fire

Venus today is a world in equilibrium, but it is a brutal equilibrium. Its surface temperature remains nearly constant, day and night, year after year. Volcanic activity may still reshape parts of the surface, but the overall climate remains unchanged. The runaway greenhouse effect has long since completed its course, leaving behind a planet that radiates immense heat into space while remaining perpetually hot.

Spacecraft that have descended to the surface have survived only minutes before being destroyed by the extreme conditions. Yet these brief glimpses have revealed a landscape shaped by volcanism, with vast plains, fractured crust, and signs of a dynamic geological past. Venus is not a dead planet; it is an active one, trapped beneath an atmosphere that has sealed its fate.

The Deeper Meaning of Venus’s Heat

Why is Venus so hot? The answer lies not in a single factor, but in a chain of physical processes that reinforced one another over geological time. Proximity to the Sun initiated warming. Water vapor amplified that warming. The loss of water removed critical climate regulation. Carbon dioxide accumulated unchecked. The greenhouse effect ran away until the planet crossed a threshold from which it could not return.

This story is scientifically precise, but it is also deeply moving. Venus reminds us that planets have histories, that they evolve, and that small differences can lead to radically different outcomes. It shows that physics is not abstract or distant, but actively shapes the destinies of worlds.

In studying Venus, we learn not only about a planet shrouded in clouds, but about the forces that govern climate, habitability, and change across the universe. Venus stands as a monument to the power of the runaway greenhouse effect, a warning written in heat and pressure, and a testament to the profound influence of atmospheric physics on the fate of planets.