For nearly two decades, astronomers have stared into the deep past of the universe and found something that did not make sense.

In a cosmos born from the Big Bang, where structure was expected to grow slowly and patiently over billions of years, researchers instead discovered something startling: massive, elliptical galaxies already fully formed just a few billion years after everything began.

These were not youthful galaxies brimming with raw potential. They were mature. Their stars were already old. Their reservoirs of cold gas, the essential fuel for new star formation, were nearly gone. They appeared settled, evolved, and strangely ancient for such a young universe.

According to standard ideas of cosmological structure formation, galaxies should grow gradually, building themselves up through countless mergers and gravitational encounters over the full span of 14 billion years. Early galaxies were expected to be chaotic nurseries of newborn stars, not quiet giants that had already lived through their most dramatic chapters.

And yet, there they were.

The question lingered: how could something so massive grow up so fast?

Now, an international team led by Nikolaus Sulzenauer and Axel Weiß at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) believes they have found a crucial piece of the puzzle.

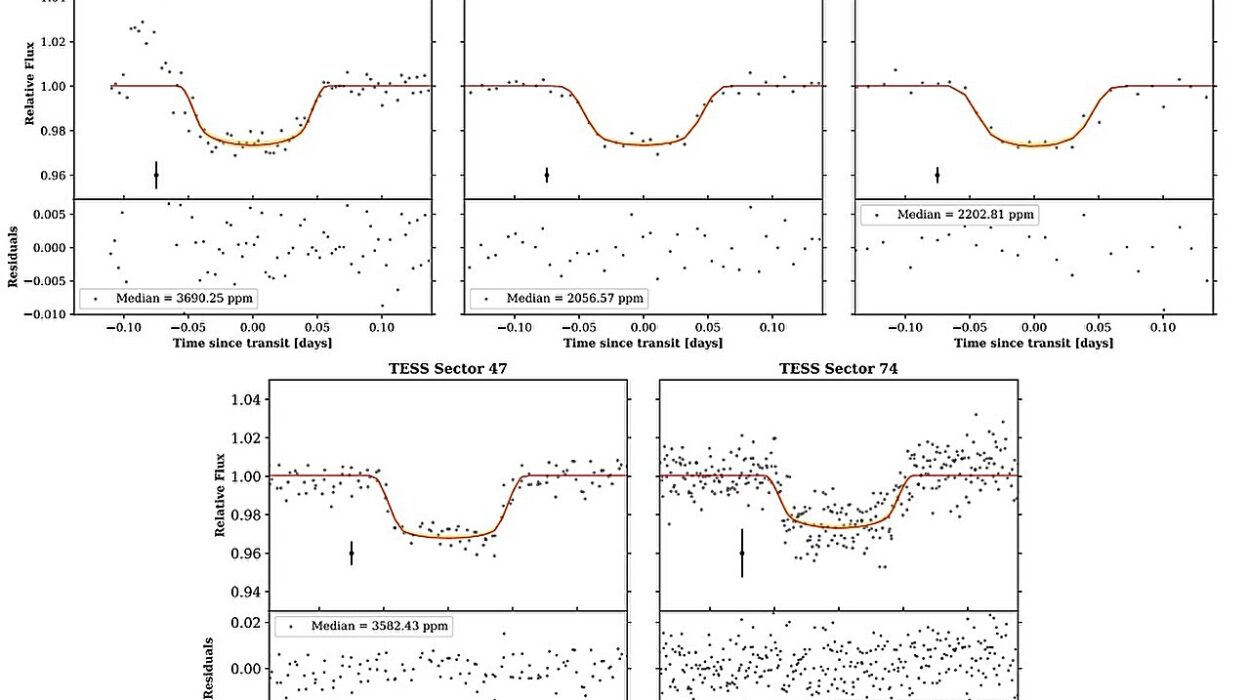

Their answer lies in a spectacular region of the early universe, observed through the extraordinary vision of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

A Glimpse Into a Collapsing Giant

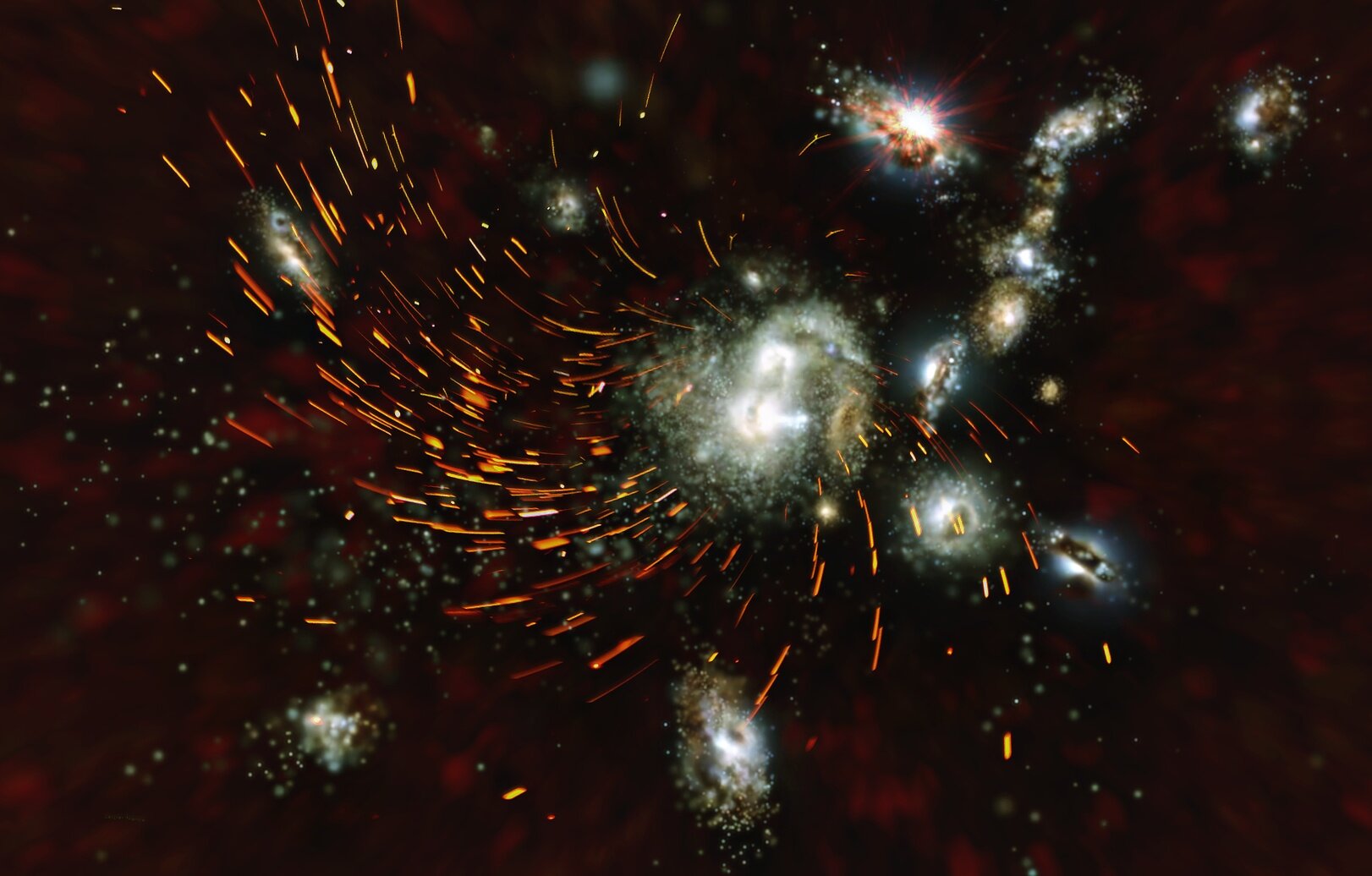

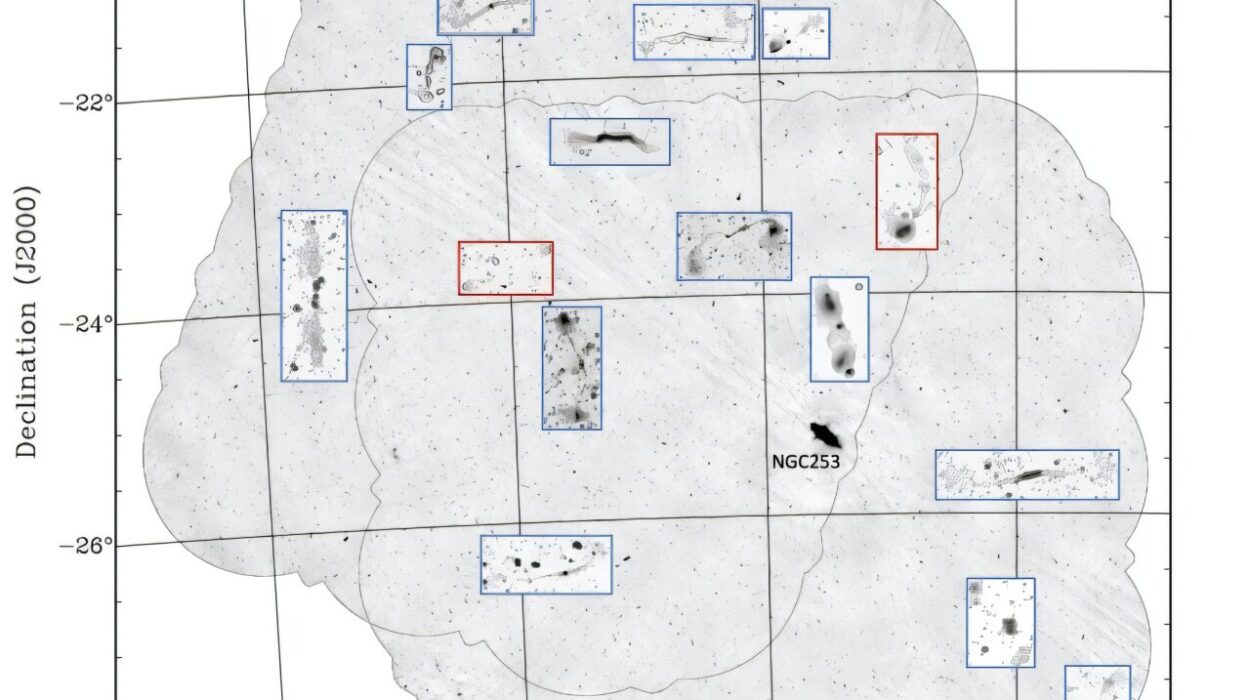

The team turned their attention to a distant protocluster known as SPT2349-56. What they saw was not a calm gathering of galaxies, but a cosmic storm in progress.

This protocluster appears as it existed just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, a time when the universe was only about 10% of its current age. It sits in the southern constellation Phoenix, glowing faintly in wavelengths invisible to human eyes but brilliantly visible to millimeter observatories like ALMA.

SPT2349-56 is no ordinary structure. It holds the record as the most vigorous stellar factory ever observed.

At its heart are four tightly interacting galaxies, locked in a gravitational dance so intense that they forge one new star every 40 minutes. To appreciate that speed, consider that the entire Milky Way produces only three or four stars in a whole year.

Here, stars ignite in bursts of breathtaking intensity.

But this frenzy is not random chaos. It is driven by something deeper: the collapse of a major primordial structure that has broken away from the universe’s general expansion.

According to the team, the densest regions of matter in the early cosmos must have decoupled from cosmic expansion remarkably early. Instead of continuing to drift apart with space itself, they began collapsing inward under their own gravity.

What followed was explosive.

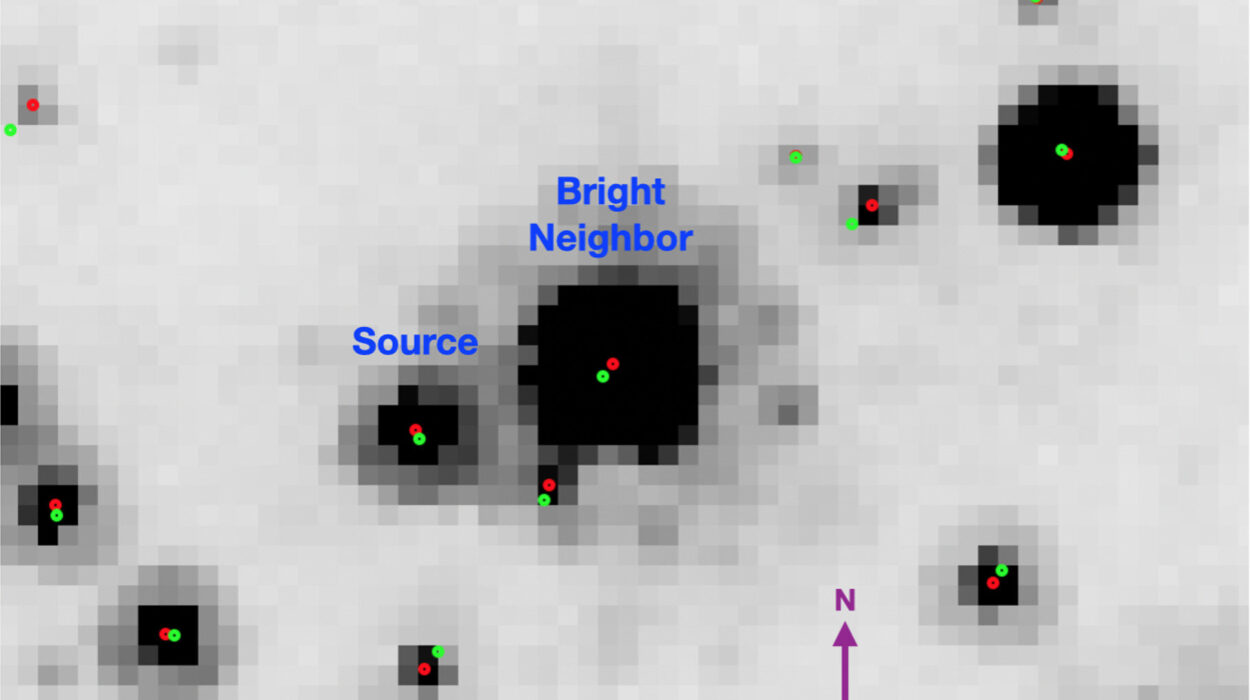

As gas compressed, it ignited what Sulzenauer describes as a cosmic firework display. The gas heated dramatically, glowing powerfully at far-infrared to millimeter wavelengths. These luminous signals acted like beacons across cosmic time, allowing telescopes such as ALMA and the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) to capture the scene.

The Beads on a String

What the researchers uncovered in the core of SPT2349-56 was even more dramatic than expected.

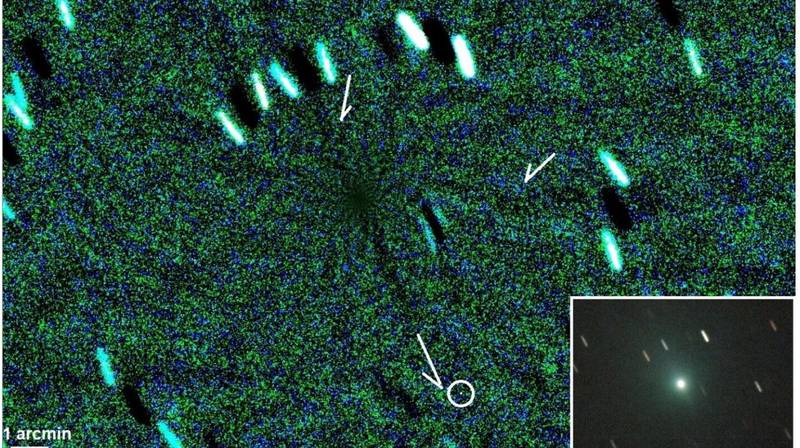

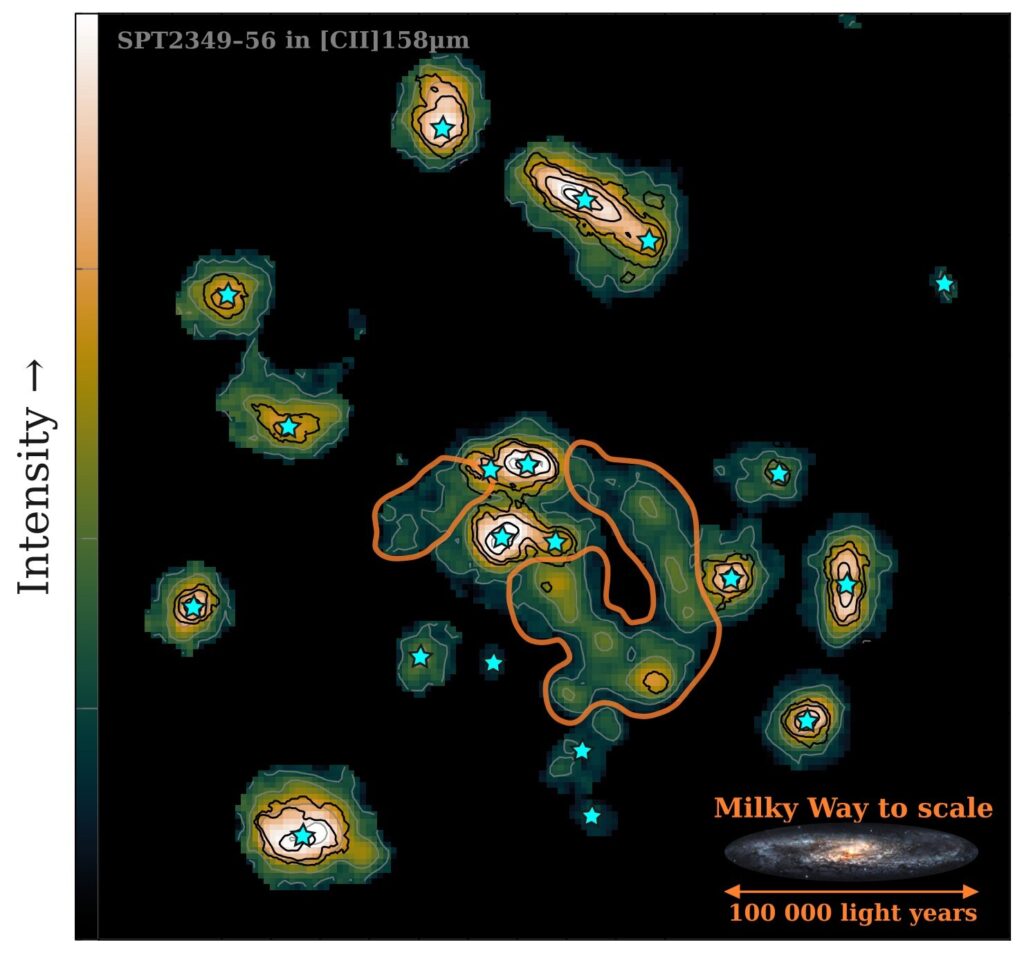

The central quartet of galaxies launches enormous tidal arms, flung outward at speeds of 300 kilometers per second. These structures stretch across regions far larger than the Milky Way.

They glow intensely at submillimeter wavelengths, their brightness amplified tenfold by shock waves that excite ionized carbon atoms. This bright emission was not just beautiful—it was informative. It allowed the team to measure the precise motion of gas being hurled outward in what resembles a spiral of glowing beads encircling the protocluster’s core.

The image is almost poetic: a necklace of cosmic debris threading through space, marking the violent interactions underway.

Then came the surprise.

Clumps of tidal debris did not simply dissipate into darkness. Instead, they linked outward to a chain of 20 additional colliding galaxies in the outer regions of the collapsing structure.

It was not an isolated event. It was a coordinated transformation.

For the first time, astronomers were witnessing what Sulzenauer calls the onset of a cascading merging transformation.

Within the protocluster’s dense core are about 40 gas-rich galaxies. According to the team’s findings, most of them will not survive as distinct systems. They will collide, merge, and ultimately be destroyed as separate entities. In less than 300 million years, they are expected to coalesce into a single, massive elliptical galaxy.

In cosmic terms, this is a blink of an eye.

Rethinking How Giants Are Born

The prevailing picture of galaxy growth has long been hierarchical. Small galaxies merge into larger ones, which merge again and again, gradually building up mass over billions of years.

But SPT2349-56 suggests something more abrupt.

Instead of a slow accumulation, some giant ellipticals may emerge from the rapid collapse and coalescence of a major primordial structure. In the time it takes the Sun to orbit the center of the Milky Way once, a colossal galaxy might be born.

This idea represents a significant shift.

The protocluster’s dense regions appear to have broken away from cosmic expansion astonishingly early, collapsing inward and assembling entire clusters in a rush of gravitational fury. The compression of gas fueled extraordinary bursts of star formation, while tidal forces flung matter outward, weaving galaxies together into an interconnected web.

To test whether this dramatic collapse could truly explain the formation of modern giant ellipticals, team members Duncan MacIntyre and Joel Tsuchitori ran detailed numerical simulations.

These simulations connected what is seen in SPT2349-56 to more mature galaxy clusters observed at later cosmic times. The result was striking. The simulated outcomes closely matched real clusters we see in the present universe.

This connection suggests that major, simultaneous mergers may not be rare accidents, but essential steps in the formation of massive galaxies.

The Lingering Mysteries

Yet even as the pieces fall into place, many mysteries remain.

The merging process creates powerful shock waves. Gas heats dramatically. Supermassive black holes likely grow within the merging galaxies, contributing additional heating and energy. How all these forces interact—and how they affect the remaining fuel for star formation—is still unclear.

Scott Chapman of Dalhousie University notes that it may be too early to claim full understanding of the “early childhood” of giant ellipticals. The interplay between merger shocks, black hole growth, and gas heating remains complex and only partially understood.

But what is clear is that astronomers have moved significantly closer to linking the tidal debris seen in young protoclusters to the enormous elliptical galaxies that dominate the centers of today’s galaxy clusters.

The bridge between past and present is becoming visible.

Why This Discovery Matters

For years, massive elliptical galaxies in the early universe stood as a quiet challenge to cosmology. They seemed to contradict the expected timeline of structure formation. Their very existence hinted that something fundamental about galaxy growth was missing from our understanding.

SPT2349-56 offers a glimpse of the missing chapter.

It reveals that under the right conditions, the universe does not always build slowly. Sometimes, it collapses inward in spectacular fashion. Sometimes, dozens of galaxies rush together in a gravitational cascade that reshapes them forever. Sometimes, the birth of a giant is not gradual but explosive.

By capturing this moment just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang, astronomers have effectively witnessed the transformation of a dense protocluster into a future giant elliptical galaxy. They have observed, in real time across cosmic history, the mechanisms that may explain how ancient, massive ellipticals appeared so early.

This matters because it strengthens the connection between the universe we see today and the universe that first emerged from darkness. It helps explain how heavy elements like carbon are heated and transported throughout early clusters. It refines our models of how gravity, gas, and mergers sculpt cosmic structure.

Most of all, it reminds us that the universe’s history is not a slow, steady march. It is punctuated by episodes of astonishing intensity.

In the glowing tidal arms of SPT2349-56, in the beads of gas racing at 300 kilometers per second, and in the rapid destruction and rebirth of 40 merging galaxies, we see the early universe not as a quiet nursery, but as a place of breathtaking transformation.

And in that transformation, the mystery of the giant ellipticals begins to yield its secrets.

Study Details

Nikolaus Sulzenauer et al, Bright [C II]158 μm Streamers as a Beacon for Giant Galaxy Formation in SPT2349-56 at z = 4.3, The Astrophysical Journal (2026). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae2ff0. iopscience.iop.org/article/10. … 847/1538-4357/ae2ff0