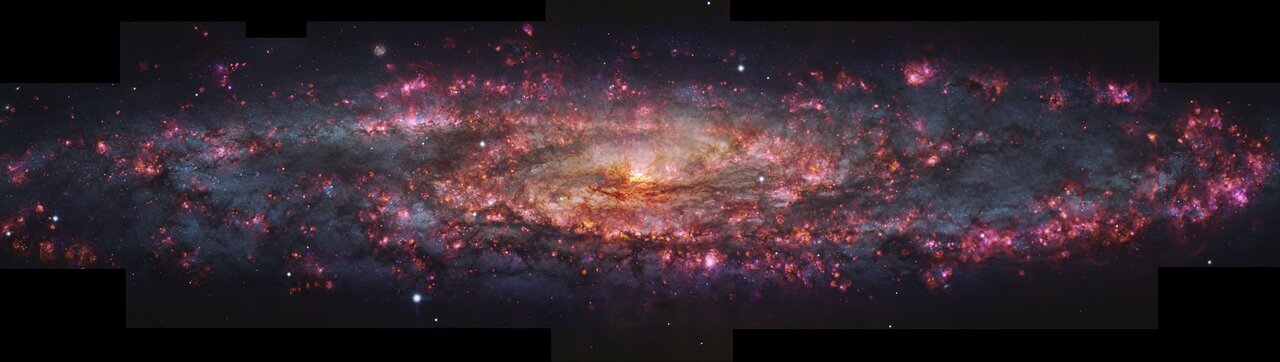

In the dark stillness of the universe, 11 million light-years from Earth, a stunning cosmic portrait has emerged. Like an artist brushing life onto a canvas, astronomers have painted the Sculptor Galaxy—not in broad strokes, but in a breathtaking symphony of color, motion, and detail never seen before.

This isn’t just a pretty picture. It’s a scientific revelation.

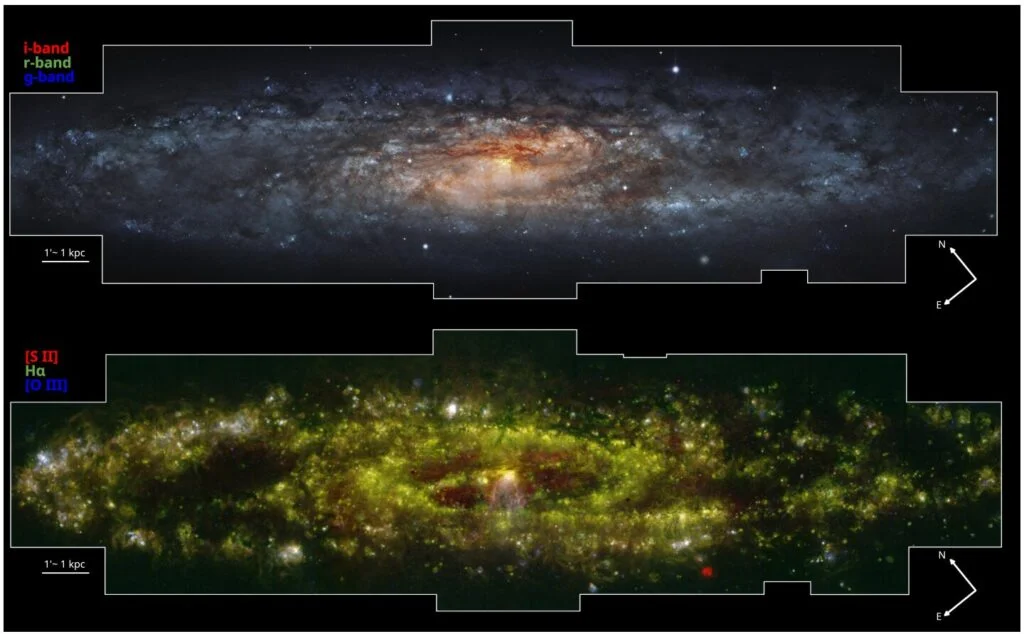

Using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), a team of astronomers led by Enrico Congiu has created the most intricate image ever taken of the Sculptor Galaxy (also known as NGC 253), capturing it in over a thousand colors simultaneously. Each hue reveals secrets about how stars are born, how they age, and how galaxies like ours are sculpted over time.

The result is a map of stellar life on a galactic scale—a swirling blend of pinks, blues, and invisible fingerprints of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, and more. It’s a time machine, a biography, and a celestial autopsy all at once.

A Cosmic Masterpiece in a Thousand Colors

If typical galaxy photos are snapshots, this new image is a full cinematic feature in ultra-high definition.

To craft it, scientists used the MUSE (Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer) instrument mounted on ESO’s VLT in Chile. Unlike a traditional camera, which records limited colors, MUSE dissects light into its full spectrum at every single pixel. Every location in the galaxy is studied in incredible detail across thousands of wavelengths.

“Galaxies are incredibly complex systems that we are still struggling to understand,” said Congiu, who led the study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics. “This image gives us the ability to see those complexities not just in a small part of the galaxy—but across the entire structure.”

Over the course of 50 observing hours, researchers stitched together more than 100 exposures to cover an area roughly 65,000 light-years wide—half the diameter of the Milky Way. The Sculptor Galaxy, seen edge-on from Earth, appears as a luminous river of stars, dust lanes, and star-forming regions that sparkle with pink ionized hydrogen.

A Galactic Laboratory in Our Backyard

Located in the constellation Sculptor, NGC 253 is a starburst galaxy—a cosmic furnace where stars are forming at an unusually high rate. It’s a perfect testbed for astronomers to study how stars live and die.

“The Sculptor Galaxy is in a sweet spot,” Congiu said. “It’s close enough that we can resolve its internal structure and study its building blocks in exquisite detail, but still large enough that we can see how the pieces fit into the whole system.”

Each color in the image tells a story. The youngest, hottest stars emit in blue and ultraviolet, while older stars shine more red. Clouds of glowing pink hydrogen trace the locations of active star birth. Patterns in the color also reveal the chemical fingerprints of the elements forged inside stars, now spread across the galaxy by supernova explosions.

A Graveyard of Stars—and a New Way to Measure Distance

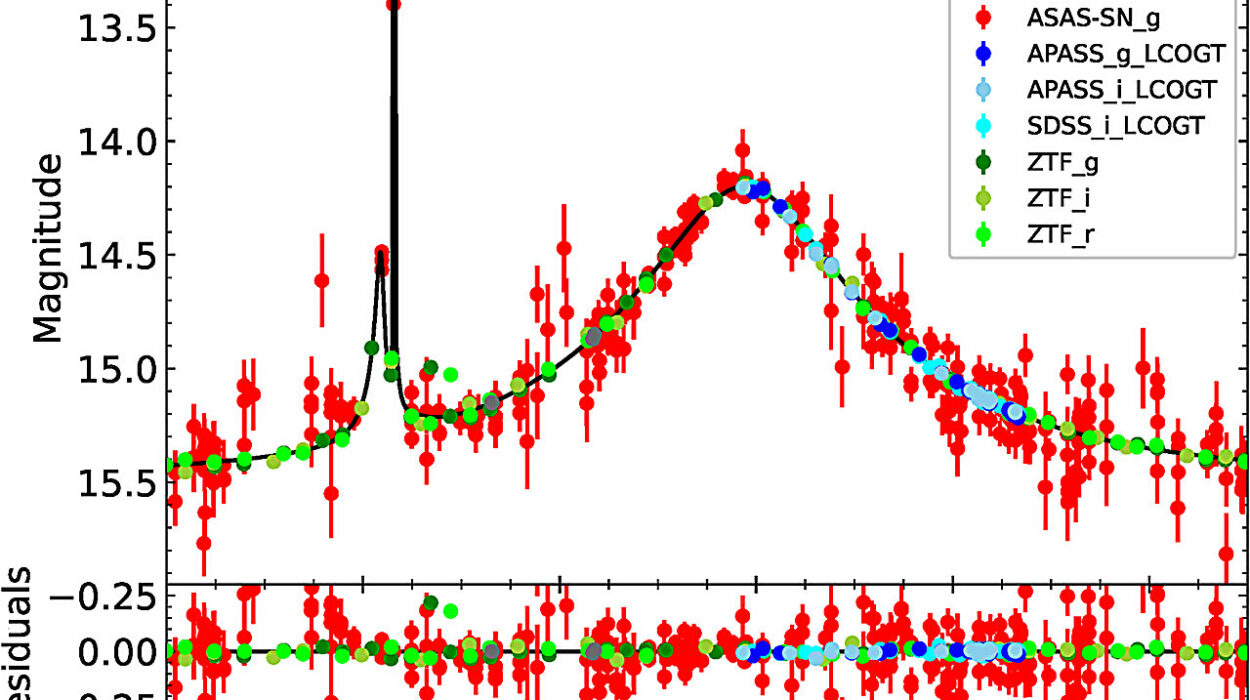

Among the discoveries already drawn from this thousand-color map: about 500 planetary nebulae, glowing shells of gas cast off by dying sun-like stars. That’s five times more than typically observed in galaxies beyond our Local Group.

“Beyond our galactic neighborhood, we usually deal with fewer than 100 detections per galaxy,” said Fabian Scheuermann, a doctoral researcher at Heidelberg University and co-author of the study. “Finding 500 in Sculptor is extraordinary.”

Planetary nebulae are not only visual marvels; they’re also scientific tools. Because they have well-understood brightness profiles, astronomers use them to calculate accurate distances to galaxies.

“Verifying the distance to a galaxy is a critical foundation,” said Adam Leroy, co-author and professor at The Ohio State University. “Everything else—from star formation rates to chemical composition—depends on knowing that distance precisely.”

From Star Nurseries to Intergalactic Winds

But the discoveries don’t end there. This new image will serve as a cosmic roadmap for years to come, guiding researchers as they explore questions about galactic evolution that are still unanswered.

One of the most puzzling: how do small-scale processes—like individual stars forming or dying—end up influencing the large-scale shape and future of an entire galaxy?

“How such small processes can have such a big impact on a galaxy whose entire size is thousands of times bigger is still a mystery,” Congiu said.

Future studies using this galactic atlas will track how gas flows through the galaxy—how it enters, cools, clumps together, ignites into stars, and is blown back into space by violent winds. These stellar winds, driven by supernovae and newborn stars, shape the galaxy’s chemical makeup, redistribute mass, and sometimes even shut down future star formation.

The Science of Awe

While the image serves as a rich trove of data for astrophysicists, it is also, in a very human sense, beautiful.

The sweeping colors, the tendrils of dust, the glimmering arcs of light—they are reminders that science and wonder are not separate. That in decoding the cosmos, we do not strip it of its poetry, but instead understand why the poetry exists.

In many ways, the Sculptor Galaxy is a mirror. Though far away, it reflects our own Milky Way’s structure and story. Studying it in such fine detail helps us peer backward in time, to understand how galaxies like ours were born, how they change, and how they might end.

In the thousand colors of Sculptor, we see the fingerprints of time—starlight from long-dead suns, gas clouds in mid-creation, and mysteries still waiting to be uncovered.

And for all the technology, algorithms, and telescopic wizardry involved, the heart of this image lies in a simple truth: the universe is alive with stories. We only have to learn how to read them.

Reference: E. Congiu, et al. The MUSE view of the Sculptor galaxy: survey overview and the

planetary nebulae luminosity function. Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). www.eso.org/public/archives/re … eso2510/eso2510a.pdf