Galileo Galilei was born under the wide Tuscan sky on February 15, 1564, in the city of Pisa, then part of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. The Renaissance was flourishing—Michelangelo had painted the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Leonardo da Vinci had filled notebooks with sketches of flying machines, and the world teetered on the edge of rediscovering its sense of wonder. Into this world came a child who would challenge not only the beliefs of his time but the very structure of the universe itself.

His father, Vincenzo Galilei, was a skilled musician and a deep thinker, a man who did not accept authority easily—not even the revered theories of Aristotle, which dominated intellectual life for centuries. This skepticism, this insistence on testing ideas rather than simply revering them, would seep into young Galileo like ink into water. His mother, Giulia, was more pragmatic, more grounded in the worries of raising a family in uncertain economic conditions.

Galileo was the eldest of six children. Early on, it was clear that his mind was not content with the everyday. He observed things others ignored. A swinging chandelier in the Pisa Cathedral led him, years later, to discoveries about pendulums. As a boy, his education was first directed toward medicine—his father hoped he would become a profitable physician—but the call of mathematics and natural philosophy proved irresistible.

The Geometry of Curiosity

At seventeen, Galileo enrolled at the University of Pisa, technically studying medicine but increasingly drawn toward mathematics, thanks in part to the influence of Ostilio Ricci, a court mathematician. Galileo found the structured elegance of geometry intoxicating. There was something divine, he felt, in the language of numbers and shapes—an order behind the apparent chaos of the world.

His studies of motion began in the most mundane of places. He dropped objects from the Leaning Tower of Pisa—not, as some myths suggest, in a dramatic public demonstration, but likely in quiet experiments to test how quickly they fell. What he discovered stood in direct contradiction to centuries of Aristotelian dogma: objects of different weights fall at the same rate in a vacuum. Galileo could not yet create a vacuum, but he saw enough to question everything.

He left the university without a degree in 1585 due to financial constraints but continued to study independently. Over the next few years, he taught mathematics in Florence and Siena, and by 1589, he returned to Pisa as a professor. There, he sharpened his critique of Aristotle, often through both experiment and biting wit. This earned him admirers and enemies alike.

Florence, Falling Bodies, and Rising Tensions

By 1592, Galileo had moved to the University of Padua, under the more liberal rule of the Venetian Republic. There, he taught geometry, mechanics, and astronomy. Padua was fertile ground for innovation, and Galileo thrived. He invented a military compass, improved designs for mechanical instruments, and began deep investigations into the nature of motion.

This period also brought more personal complexity. Galileo began a relationship with Marina Gamba, a woman from Venice. They never married—largely because of Galileo’s social status and concerns over inheritance and respectability—but they had three children: two daughters and a son. His daughters, Virginia and Livia, were eventually sent to a convent, a decision likely made for social and financial reasons but one that haunted Galileo with guilt.

In Padua, his lectures became legendary. Students packed halls to hear him dissect Aristotle, champion Archimedes, and describe nature not as a body of truths to be memorized but as a book to be read in the language of mathematics. He published his early work on motion in this era, laying foundations for what would eventually become Newton’s laws.

But it was not until he turned his gaze toward the heavens that his name would echo across centuries.

A Telescope Toward the Truth

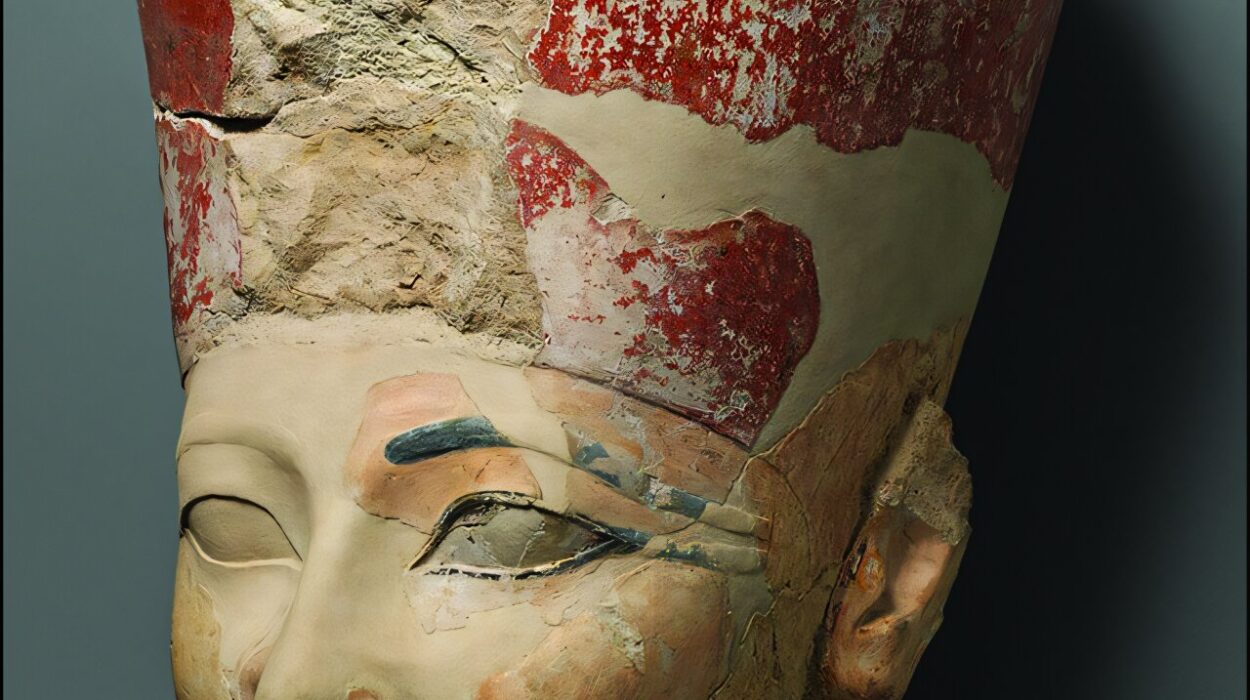

In 1609, Galileo heard news of a device invented in the Netherlands: a tube fitted with lenses that made distant objects appear closer. Inspired, he built his own telescope—far superior to the originals—and aimed it at the night sky. What he saw was not only breathtaking but heretical.

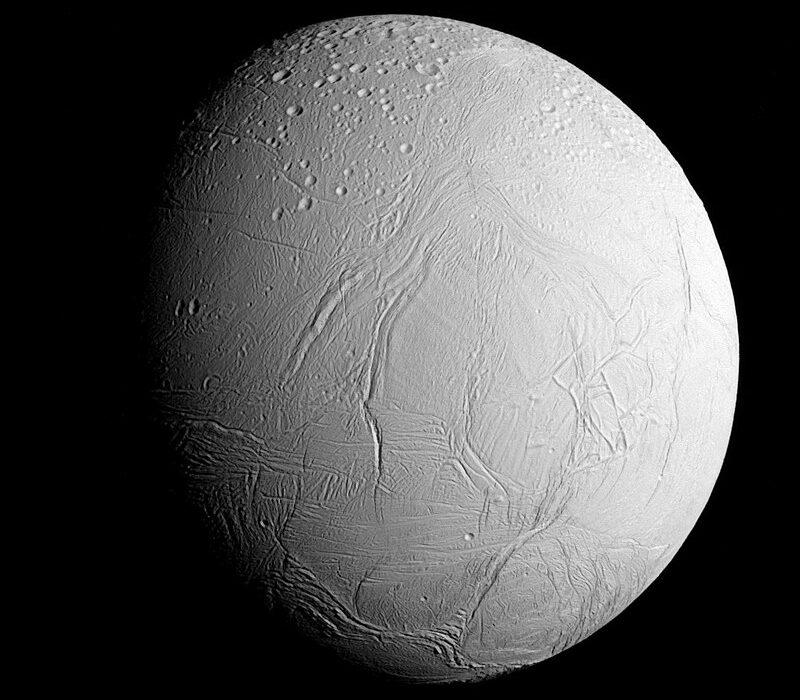

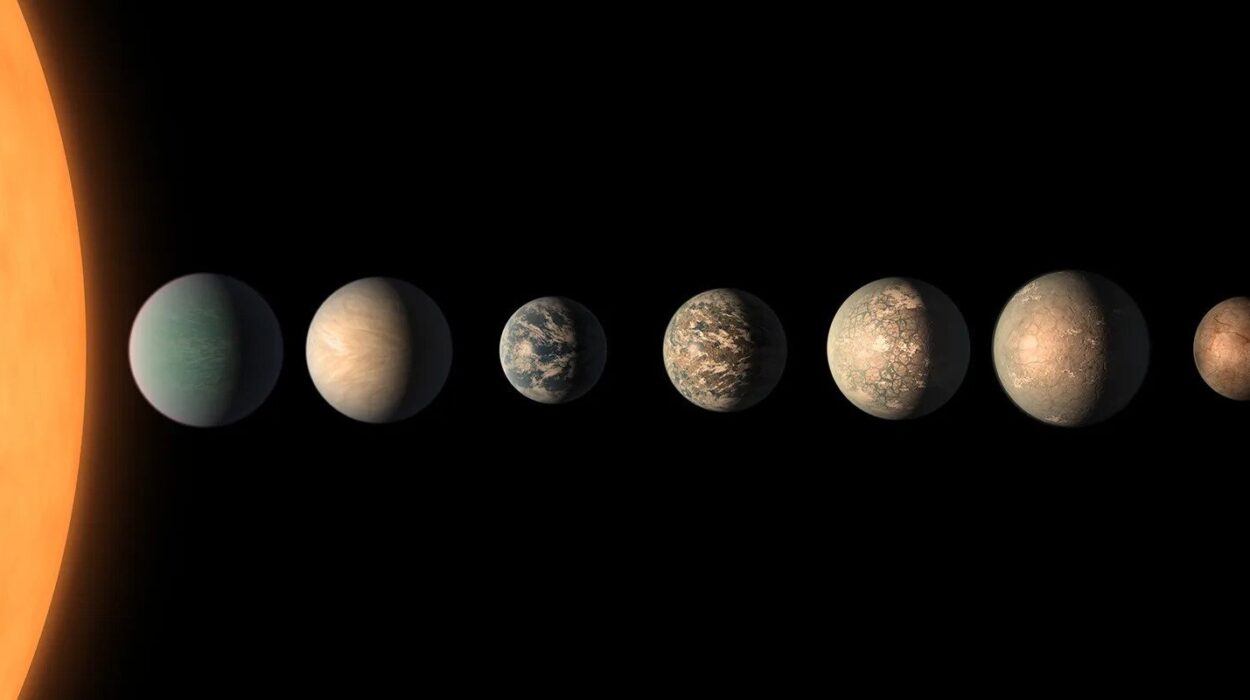

He observed the Moon and saw craters, mountains, and valleys—hard, rugged terrain that shattered the belief in celestial perfection. The stars, once thought to be few and fixed, revealed themselves as countless and scattered through infinite space. Jupiter had moons—four of them, orbiting not the Earth, but the giant planet itself. Galileo’s universe was unraveling.

He published his findings in 1610 in a small book titled Sidereus Nuncius, or The Starry Messenger. It was a cosmic explosion. Galileo named the moons of Jupiter the “Medicean Stars,” in honor of his patrons, the Medici family, securing not only funding but also political protection. But his discoveries had larger implications than courtly flattery.

The heavens were no longer immutable. The Earth was not unique in having a satellite. The universe, once a tidy hierarchy with Earth at its unmoving center, had begun to tilt. Copernicus, whose sun-centered model had long been dismissed, suddenly seemed more plausible. Galileo did not yet publicly endorse heliocentrism in full, but the seeds were sown.

The Heretic in the Shadows

As Galileo’s fame grew, so did the danger. The Catholic Church, reeling from the Protestant Reformation and the scientific upheavals of the previous century, had begun tightening its control over intellectual life. The idea that Earth moved around the Sun was more than just an astronomical hypothesis—it was a challenge to the theological cosmology that placed humanity at the center of creation.

In 1616, the Church declared the heliocentric model “formally heretical.” Galileo was warned not to hold or teach it. He obeyed—at least publicly. For the next several years, he focused on less controversial topics, continuing his research and cultivating relationships with Church officials who sympathized with science.

In 1623, Galileo saw a glimmer of hope. A new pope, Urban VIII, ascended to power. Urban was an intellectual and had once admired Galileo’s work. Encouraged, Galileo sought permission to write a book discussing the heliocentric and geocentric models. He received it, with conditions: the book must remain neutral and not claim that one model was correct.

The result was Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems, published in 1632. Structured as a conversation between three characters—Salviati, who supports heliocentrism; Simplicio, a defender of Aristotle; and Sagredo, an open-minded layman—the book was a masterclass in rhetorical brilliance. But it was also a dangerous game. Though Galileo claimed neutrality, Simplicio—who argued for the geocentric model—was portrayed as foolish, and many readers saw him as a stand-in for the Pope.

Trial of a Mind

The Church was not amused. In 1633, Galileo was summoned to Rome to face the Inquisition. He was seventy years old, ill, and exhausted. Accused of violating the 1616 edict, he was interrogated, threatened with torture, and eventually forced to recant.

He knelt before the tribunal and muttered the words they demanded. He denied that the Earth moved. He confessed his error. Legend has it that as he rose, he whispered, “E pur si muove”—“And yet it moves.” There is no contemporary evidence that he said it, but the phrase captures the essence of his defiance.

Galileo was sentenced to house arrest for the remainder of his life. His books were banned. His name was tarnished in official Church circles. But his mind, that indomitable forge of questions and insight, remained unbroken.

The Final Observations

Confined to his villa in Arcetri near Florence, Galileo continued to write. His most profound work from this period, Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences, summarized decades of work on motion and strength of materials. Smuggled to the Netherlands and published in 1638, it laid the foundation for classical mechanics.

By then, Galileo had gone blind, likely due to cataracts and glaucoma. Yet he dictated his thoughts to loyal students and corresponded with philosophers, mathematicians, and astronomers across Europe. In isolation, he built bridges of thought that would outlast the walls of his confinement.

His daughter, now Sister Maria Celeste, was one of his few comforts. She wrote to him frequently, offering spiritual support and household management. Her death in 1634 devastated him more than any trial. In her letters, we see Galileo not as the colossus of science but as a grieving father, full of love, longing, and vulnerability.

On January 8, 1642, Galileo died in his sleep. He was seventy-seven. He had seen the universe in ways no human had seen before—and had paid the price for saying so.

Echoes Across Centuries

Galileo Galilei’s impact cannot be overstated. He was not the first to use a telescope, but he was the first to use it as a tool of rigorous investigation. He did not invent heliocentrism, but he breathed life into it, giving it evidence, eloquence, and defiance. He fused observation with mathematics, laying the groundwork for the scientific method.

Isaac Newton would later say, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” One of those giants, indisputably, was Galileo.

In 1992—three and a half centuries after his trial—the Catholic Church formally acknowledged its error. Pope John Paul II expressed regret over how Galileo had been treated. But Galileo’s true absolution had come long before, written not in papal bulls but in the trajectory of spacecraft, the detection of exoplanets, and the arcs of falling bodies described by physicists everywhere.

He showed us that truth does not bend to power, that the stars are not beyond our reach, and that silence in the face of ignorance is the greatest heresy of all.

The Legacy of a Revolutionary Mind

Galileo’s life was a collision of cosmos and courtrooms, of silence and thunder, of devotion to truth and condemnation by dogma. He was not merely a scientist. He was a poet of the physical world, a man who saw beauty in Jupiter’s moons and wisdom in falling objects.

He taught us to look—to truly look—with tools, with reason, and with wonder. He dared to read the language of the universe when others clung to superstition. And though he lived under the shadow of censure, his legacy illuminates the world to this day.

The Earth still moves. The stars still shine. And Galileo Galilei, the man who first dared to tell the truth about both, continues to guide us through the darkness.