In the vast, star-drenched halo surrounding our Milky Way galaxy, far from the swirling center where stars cluster and planets are more commonly found, an invisible drama quietly unfolded. A distant star, unknown and unremarkable to the casual eye, began to flicker—not because it was dying, but because something massive passed in front of it, bending its light with silent precision.

That flicker, that momentary pulse in the darkness, was the only clue to a remarkable discovery.

Scientists from Vilnius University’s Faculty of Physics, working with colleagues in Poland and across Europe, have announced the detection of a rare exoplanet—named AT2021uey b—using one of the most elusive and elegant methods in astronomy: gravitational microlensing, a phenomenon Albert Einstein first predicted more than a century ago.

The study, now published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, marks just the third time in observational history that a planet has been discovered this far from the galactic center. And it was made possible by a fleeting alignment of cosmic bodies, extraordinary patience, and a deep dive into terabytes of stellar data.

A Shadow in the Halo

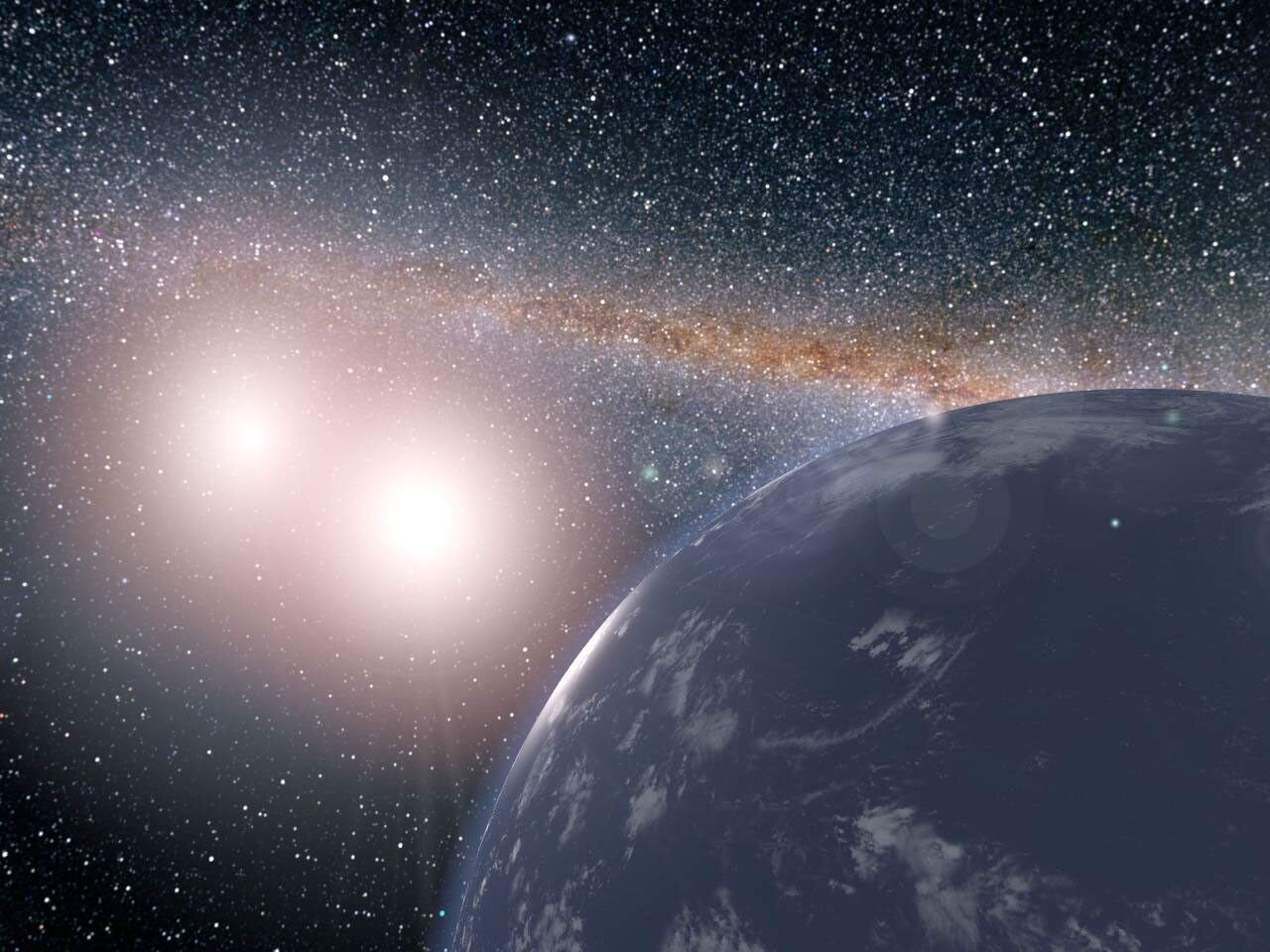

The newly discovered exoplanet is a gas giant, roughly 1.3 times the mass of Jupiter, and it orbits a small, cool M dwarf star. The entire system lies 3,262 light-years away from Earth, not nestled within the crowded galactic core or star-filled disk, but drifting in the sparsely populated galactic halo—a region typically inhospitable to planet hunting.

For astronomers, the galactic halo is like the outskirts of a distant city at night—faintly lit and mostly silent. And that makes AT2021uey b’s discovery not just unusual, but stunning.

“Most microlensing effects are recorded at the densest part of the galaxy—in its center and disk,” said Assoc. Prof. Edita Stonkutė, the Lithuanian leader of the joint Polish-Lithuanian project. “We managed to find this microlensing phenomenon quite far from the center, in the galactic halo. That’s incredibly rare.”

In fact, until now, only two other exoplanets had ever been found in this remote region.

The Universe’s Invisible Lens

The technique that made the discovery possible—gravitational microlensing—is as poetic as it is technical.

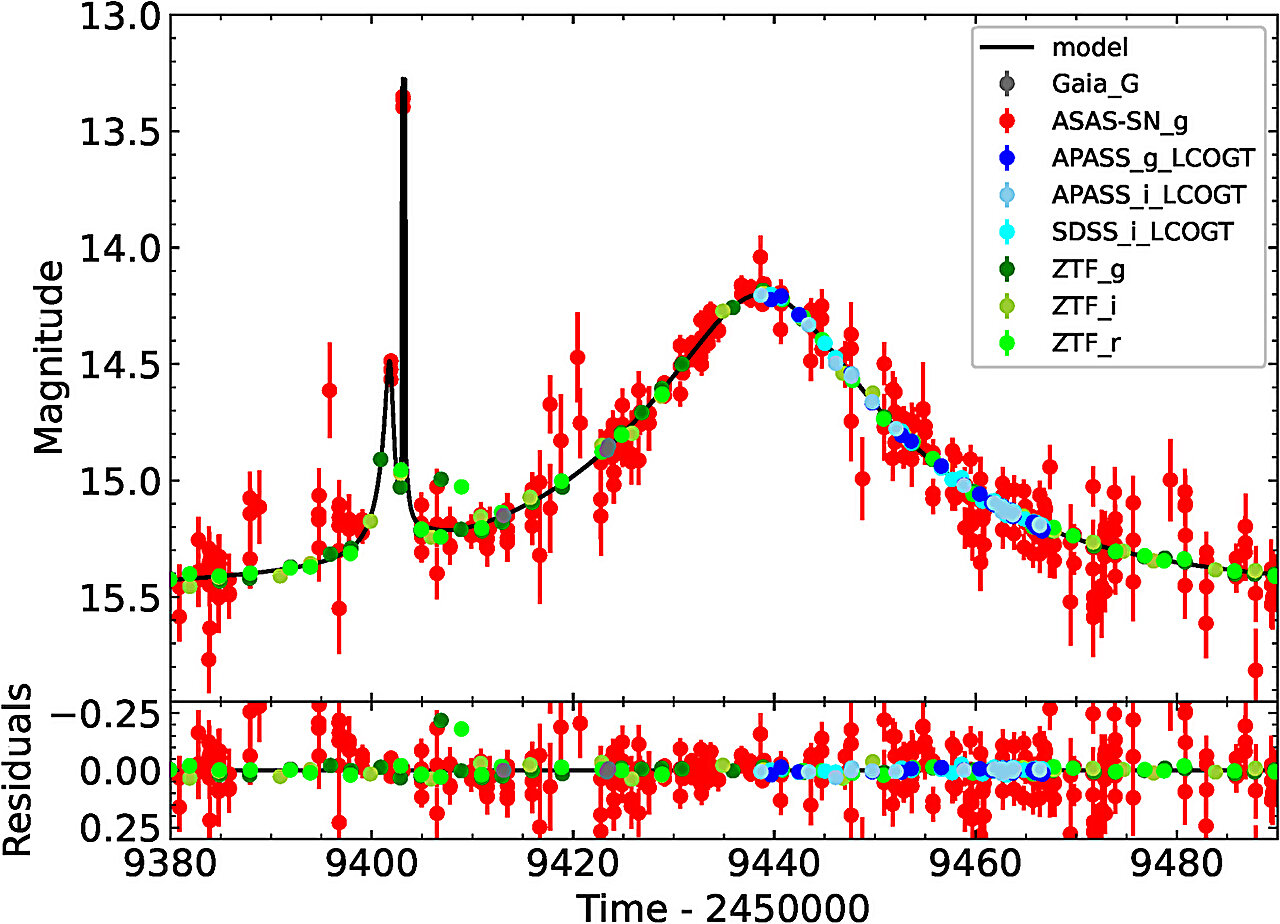

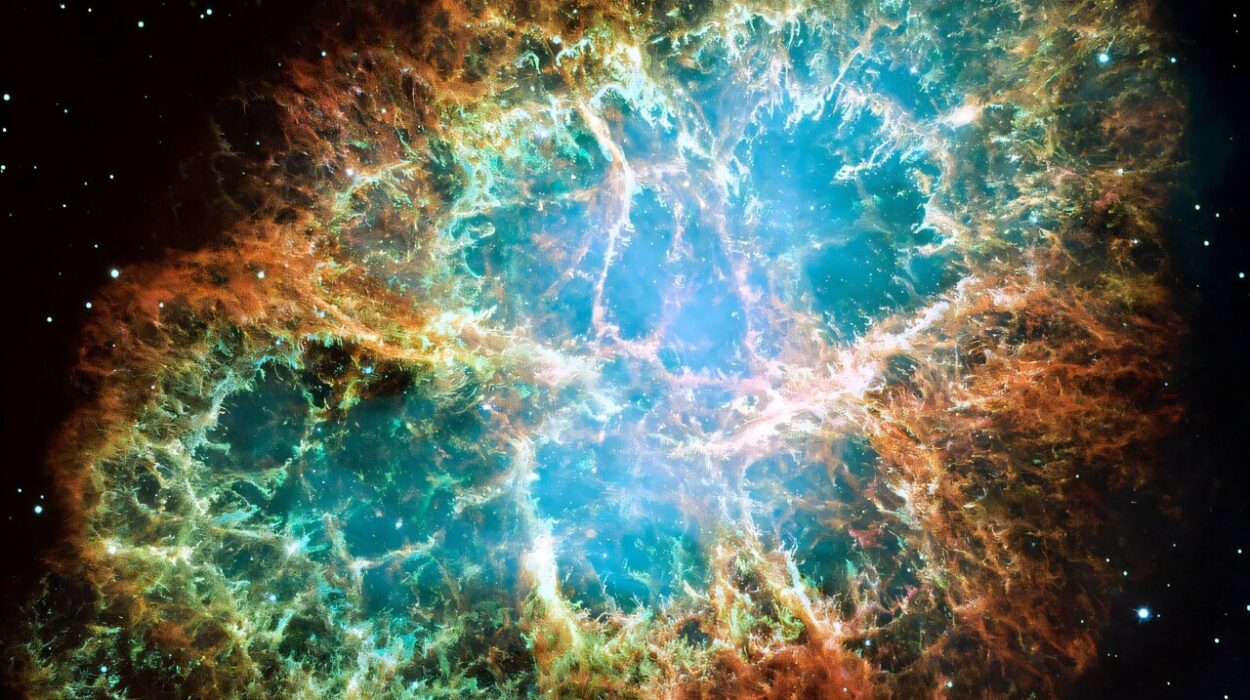

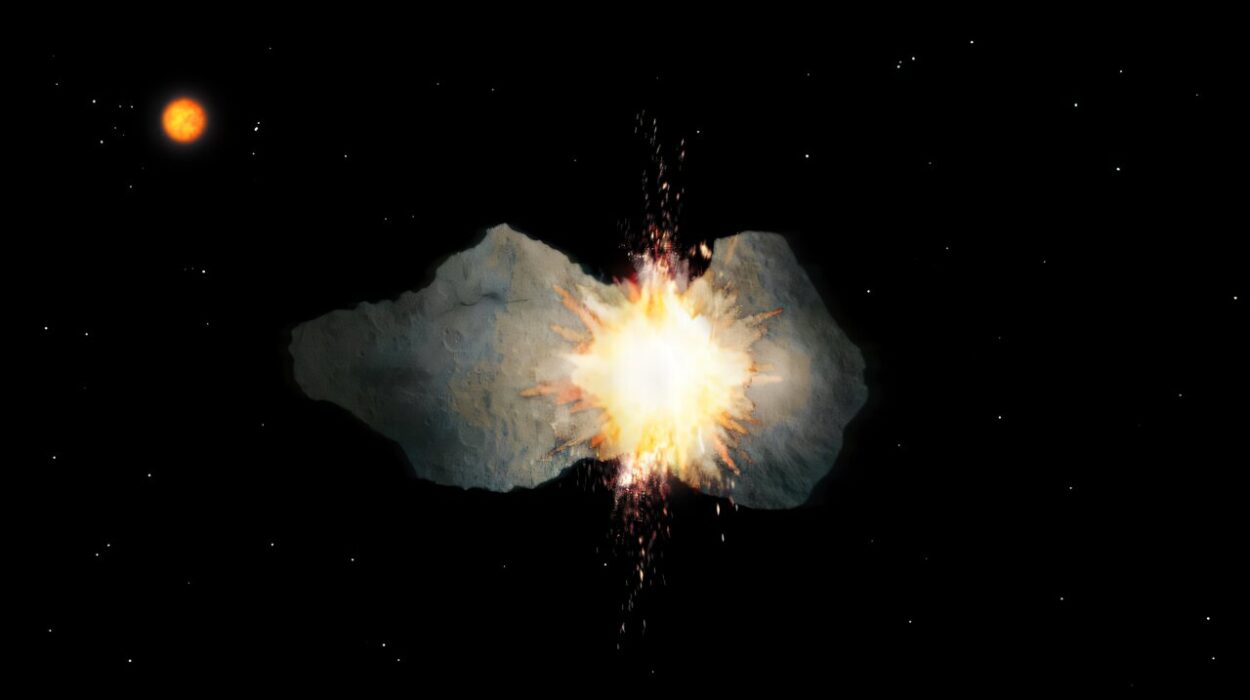

First proposed by Einstein in his theory of general relativity, microlensing occurs when a massive object, like a star or even a planet, passes directly in front of a more distant star. The gravitational field of the foreground object bends and amplifies the background star’s light, acting like an invisible cosmic lens. For a brief moment—days or weeks—the star brightens. Then it fades back to normal.

These events are rare and unpredictable. They require incredible patience, a dash of serendipity, and an eye for the unusual buried in mountains of stellar data.

“This kind of work requires a lot of expertise, patience, and frankly, a bit of luck,” said Dr. Marius Maskoliūnas, head of the Lithuanian research team. “Ninety percent of observed stars pulsate for all sorts of reasons. Only a tiny fraction show the microlensing effect. Finding them is like searching for a whisper in a storm.”

The initial signal for AT2021uey b was first observed in 2021. Years of meticulous analysis followed, combining data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia telescope and ground-based observations from the Molėtai Astronomical Observatory in Lithuania.

A Chance Meeting in Warsaw

Ironically, the project itself began not through a formal proposal or grand plan—but during a casual scientific visit.

During a trip to the University of Warsaw’s Astronomical Observatory, Dr. Maskoliūnas struck up a conversation with Prof. Łukasz Wyrzykowski, a microlensing specialist. Wyrzykowski proposed a joint research effort to sift through Gaia’s data and verify promising signals with telescopes in Lithuania.

It was a simple idea—but one that paid off.

What they found was a planet unlike Earth in every way: massive, gaseous, and slow-moving. AT2021uey b completes a single orbit around its dim host star once every 4,170 Earth days—more than 11 years.

Its discovery was aided, ironically, by its sheer size. Finding an Earth-like planet through microlensing would be exponentially more difficult.

Rethinking Planetary Systems

When astronomers found the first planet orbiting a star outside our solar system in 1995, it shook up everything we thought we knew. It wasn’t a second Earth—but a scorching-hot gas giant hugging its star at a perilously close distance.

That discovery, and the nearly 6,000 exoplanets confirmed since, have challenged old ideas and rewritten our understanding of planetary formation.

“When the first Jupiter-like planet was found so close to its star, scientists were shocked,” said Prof. Stonkutė. “As we discovered more, we saw that many planetary systems look nothing like our own. We’ve had to rethink everything—multiple times.”

The microlensing method adds yet another layer to this understanding. Unlike other methods that rely on light, microlensing can detect the invisible—from planets with wide orbits to dark objects like rogue planets and even black holes.

“If we were to add up all the visible mass in the Milky Way,” Dr. Maskoliūnas explained, “we’d get at best one-tenth of the total. That means 90% of the galaxy is still invisible to us. Microlensing gives us a way to start peering into that darkness.”

Measuring Shadows, Not Light

To explain microlensing’s magic, Dr. Maskoliūnas offers a simple metaphor.

“Imagine a bird flying past you at dusk,” he said. “You don’t see the bird itself—just its shadow. But from that shadow, you might guess its size, maybe even what kind of bird it was. Was it close or far? Was it small like a sparrow, or large like a swan?

“That’s what microlensing is. You’re not seeing the planet—you’re seeing the effect it has on the light from something behind it. You’re measuring shadows. And from those shadows, you’re reconstructing the unseen.”

The Frontier of the Unknown

AT2021uey b may not look like much—a giant planet orbiting a faint star, cloaked in darkness on the galaxy’s edge. But its discovery opens new doors to understanding the universe.

It reminds us that even in the loneliest reaches of the galaxy, planetary systems can exist. It shows that light, even when bent and filtered through gravity and time, still has secrets to reveal. And it proves that science is often a blend of planning and luck, of algorithms and awe.

As the hunt for new worlds continues, microlensing will play a growing role—not in spotlighting the obvious, but in illuminating the hidden. And somewhere, in a dim corner of the galaxy, another bird’s shadow is already passing by.

We just have to look for it.

Reference: M. Ban et al, AT2021uey: A planetary microlensing event outside the Galactic bulge, Astronomy & Astrophysics (2025). DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/202554236