On a chilly March morning in New York’s Central Park, you might notice the cherry trees budding weeks ahead of schedule. In Paris, crimson maples cling to their leaves deep into what should be winter. And across cities like Toronto and Beijing, a silent revolution is taking place—not driven by climate alone, but by something much more subtle: the city lights.

A new study published in Nature Cities offers compelling evidence that artificial lighting in urban environments is lengthening the growing season for plants by as much as three weeks compared to their rural counterparts. Based on satellite observations over seven years and across 428 cities in the Northern Hemisphere, the findings highlight a striking reality: the glow of our cities is quietly changing the rhythm of the natural world.

“The artificial night light that spills from our windows and street lamps doesn’t just light up our lives—it’s rewriting nature’s calendar,” said Lin Meng, the study’s lead author and a researcher deeply engaged in understanding the consequences of urbanization on ecological cycles.

A World That Never Sleeps

Urban life runs on illumination. From LED-lit skyscrapers to endless headlights on traffic-packed highways, cityscapes shimmer through the night like constellations flipped upside down. But while these lights keep human activities humming after dark, their impact on plants—anchored and silent—is profound.

The researchers analyzed satellite data from 2014 to 2020, measuring artificial light levels, surface air temperatures, and vegetation cycles in cities stretching from New York to Tokyo. What they discovered is both fascinating and unsettling: the amount of artificial light at night increases sharply as you move from rural landscapes to city centers—and with it, the natural growing season expands.

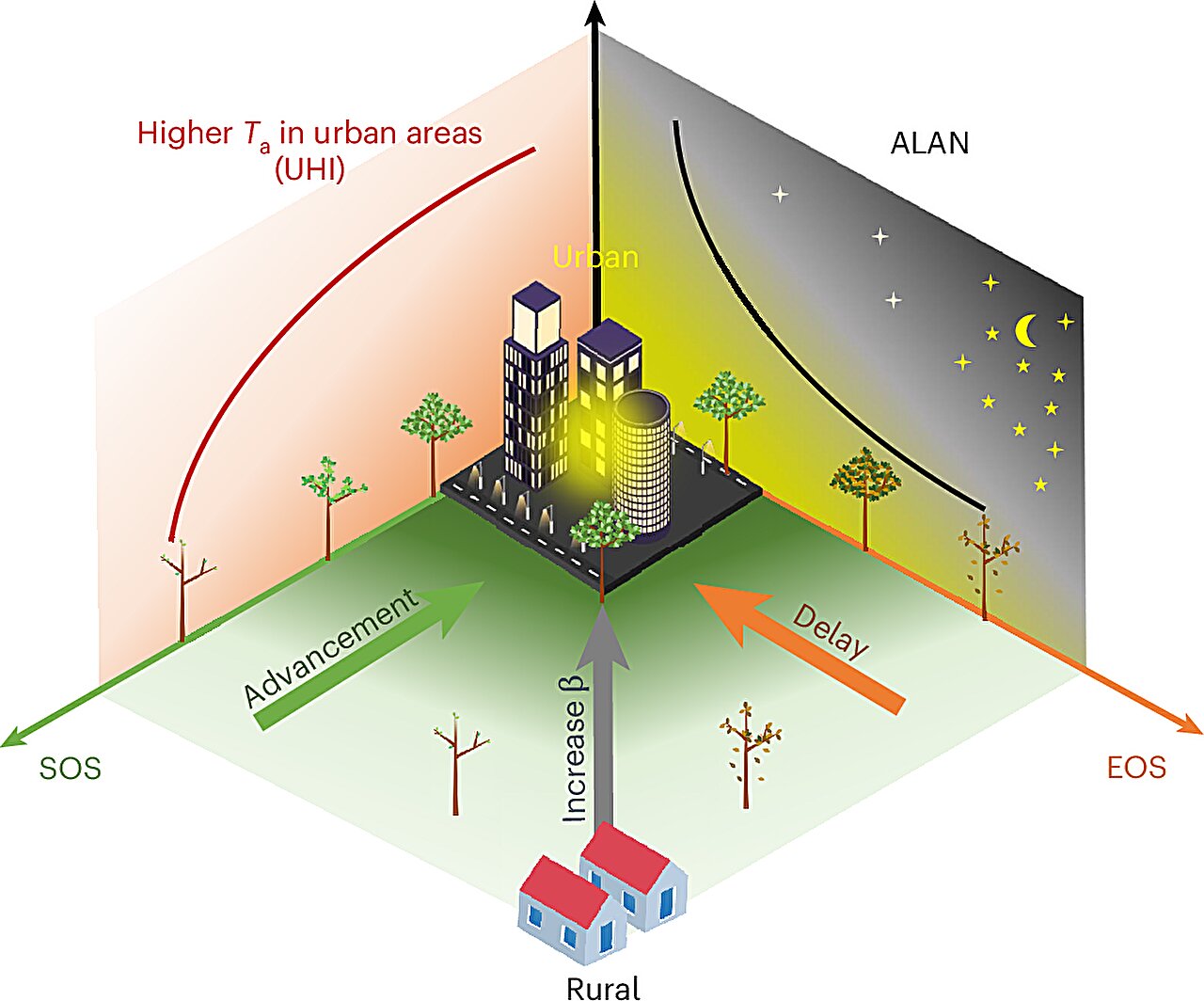

On average, trees and plants in cities begin their growing season nearly 12.6 days earlier and end it 11.2 days later than those in nearby rural areas. That’s a shift of nearly three weeks—a full season’s worth of difference, powered not by sunlight or soil, but by the very things that define modern urban life.

Heat or Light: Who’s the Culprit?

It’s long been known that cities create their own microclimates. Buildings and asphalt absorb sunlight and radiate heat, producing what scientists call “urban heat islands.” These warmer zones influence plant life by accelerating spring budding and delaying autumn leaf fall.

But Meng and her team found that light, not just temperature, is now a major player—especially in densely populated cities where the glow of artificial light is omnipresent.

“Plants respond to photoperiods—the length of daylight—as a cue for when to wake up and when to rest,” Meng explained. “But in cities, that daylight cue is now being distorted by human-made light. What we’re seeing is that artificial light is even more influential than the temperature gradient from rural to urban areas in many cases.”

Interestingly, the researchers found that the effect of artificial light is particularly strong at the end of the growing season, keeping trees green and active long after their country cousins have begun to shed their leaves. In effect, the night lights are convincing trees that autumn is still far away.

A Planet-Wide Shift with Local Signatures

While the overall pattern held true across all 428 cities studied, the team uncovered intriguing differences between continents and climate zones.

European cities showed the earliest start to the growing season, followed by Asia and then North America. Curiously, North American cities were found to be the brightest, yet didn’t always see the earliest plant responses. That points to the complexity of plant responses across different climates and perhaps, different histories of urban lighting.

Moreover, the researchers noted that in some climate zones—such as temperate regions with dry summers and cold climates without dry seasons—artificial light had a much stronger influence on when the growing season began. Yet its impact on the end of the season was remarkably consistent across all regions, suggesting a universal biological response to night-time illumination.

Enter the LED Era

In recent years, the world has seen a dramatic switch from traditional high-pressure sodium lamps to LED lighting—brighter, more energy-efficient, and whiter in spectrum. But that shift may also be deepening light pollution’s effect on plants.

“Plants are especially sensitive to the blue spectrum of light, which is more pronounced in LEDs,” Meng said. “So even if the wattage is lower, the biological impact may be stronger.”

This is still an emerging area of research. But the implications are enormous—not just for the plants themselves, but for the animals, insects, and even microbes that depend on seasonal signals.

What Happens When Nature Can’t Rest?

The effects of an extended growing season might sound harmless—even beneficial—at first glance. But nature evolved over millions of years with distinct seasonal boundaries for a reason.

When trees leaf out early, they may be more vulnerable to late-season frosts, which can damage new growth. A longer growing season also increases water and nutrient demand—factors that might strain already stressed urban ecosystems. Migratory birds and pollinators that rely on seasonal cues could find themselves out of sync with the availability of food.

In essence, urban plants are being pushed into perpetual productivity, without the restful dormancy they’ve relied on for survival. This biological overtime could have ripple effects throughout the food web.

Rethinking the Urban Glow

What can be done?

Meng and her colleagues emphasize that their study isn’t a call to turn off the lights—but rather to rethink how we illuminate our cities. Smarter, targeted lighting design that reduces unnecessary upward or outward glow could go a long way toward balancing urban function with ecological health.

City planners and lighting engineers may need to consider vegetation sensitivity in future infrastructure projects—just as they’ve learned to consider wildlife corridors or stormwater drainage.

After all, the very trees that shade our sidewalks, clean our air, and soothe our senses deserve a break, too.

A Future Under Neon Skies

The story unfolding in the leaves of urban trees is one of silent adaptation—of plants responding to a world changed by human ambition and artificial brightness.

As our cities continue to grow, the line between day and night, between spring and fall, is blurring. And though the glow may seem gentle, its consequences echo deep into the heart of ecosystems that we often take for granted.

We are, perhaps unknowingly, becoming stewards of a new season—one shaped not by the sun and stars, but by the flick of a light switch.

Reference: Lvlv Wang et al, Artificial light at night outweighs temperature in lengthening urban growing seasons, Nature Cities (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44284-025-00258-2

Love this? Share it and help us spark curiosity about science!