Imagine waking up one day and finding that the memories you have cherished—the smell of your mother’s cooking, the laughter of your children, the familiar streets of your hometown—begin to fade like mist in the morning sun. At first, it might seem harmless: a forgotten appointment, misplaced keys, or difficulty finding the right word. But slowly, the fog thickens, until even the people you love most become strangers. This is the cruel reality of Alzheimer’s disease, a condition often described as a silent thief that robs individuals of their memories, independence, and identity.

Alzheimer’s disease is not merely forgetfulness that comes with age. It is a progressive and irreversible brain disorder that gradually destroys memory, thinking skills, and the ability to perform the simplest tasks. For millions of families around the world, Alzheimer’s is not just a medical condition but a devastating personal journey filled with confusion, grief, and resilience.

In this article, we will explore the causes, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatments of Alzheimer’s disease in depth. But more than that, we will look at how science, compassion, and human determination converge in the fight against one of the most challenging health conditions of our time.

Understanding Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of all dementia cases. Dementia itself is not a specific disease but an umbrella term describing a set of symptoms affecting memory, reasoning, and social abilities severely enough to interfere with daily life. Alzheimer’s is unique in its progression and its underlying biological changes in the brain.

Named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, who first described the disease in 1906 after studying the brain of a woman who had died of an unusual mental illness, the condition is marked by two primary hallmarks: amyloid plaques (sticky clumps of protein fragments between neurons) and neurofibrillary tangles (twisted strands of tau protein inside neurons). These toxic accumulations disrupt communication between brain cells, leading to cell death and, ultimately, brain shrinkage.

Alzheimer’s develops slowly, often starting years before symptoms become noticeable. At first, the brain compensates for damage, masking the disease. Over time, however, the destruction becomes too extensive, leading to progressive decline in memory, judgment, and ability to function.

The Causes of Alzheimer’s Disease

The causes of Alzheimer’s are complex, involving a mix of genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. While scientists do not yet fully understand why some people develop Alzheimer’s and others do not, several key contributors have been identified.

Genetics and Family History

One of the strongest risk factors is age, but genes also play an important role. For most people, Alzheimer’s is not directly inherited but influenced by risk genes. The APOE ε4 gene is the most significant genetic risk factor identified so far. Having one copy of APOE ε4 increases the risk, and having two copies raises it even further, though not everyone with this gene develops the disease.

Rarely, Alzheimer’s can be caused by deterministic genes, meaning that anyone who inherits them will develop the disease. These cases, known as early-onset familial Alzheimer’s, usually appear before the age of 65 and account for less than 5% of cases.

Age and Biological Changes

Age is the greatest risk factor. Most people with Alzheimer’s are over 65, and the likelihood of developing the disease doubles every five years after this age. But why does aging make us vulnerable? Scientists believe that changes in the brain over time—such as reduced ability to clear away amyloid proteins, weakening of blood vessels, and inflammation—contribute to the disease.

Lifestyle and Environmental Factors

While genes and age are beyond our control, lifestyle factors significantly influence the risk of Alzheimer’s. Poor cardiovascular health, obesity, diabetes, smoking, lack of physical activity, and chronic stress all increase vulnerability. The “what’s good for the heart is good for the brain” principle has been supported by many studies, showing that healthy diets, regular exercise, and mental stimulation lower the risk.

Environmental exposures, such as air pollution, head trauma, and toxins, are also being studied as possible contributors.

Brain Chemistry and Neurotransmitters

In Alzheimer’s disease, important chemical messengers in the brain—especially acetylcholine—decline. Acetylcholine is critical for memory and learning, and its reduction is linked to worsening cognitive function. Imbalances in glutamate, another neurotransmitter, also play a role, contributing to brain cell damage.

Symptoms of Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s unfolds in stages, each marked by worsening symptoms. While the pace varies from person to person, the trajectory follows a common path from mild forgetfulness to profound disability.

Early Stage (Mild)

The early stage may seem subtle, often dismissed as normal aging. Common signs include:

- Forgetting recently learned information

- Difficulty recalling names or words

- Misplacing objects frequently

- Trouble with planning or solving problems

- Becoming easily confused with time or place

At this point, many people can still live independently but may rely on reminders, lists, or loved ones for support.

Middle Stage (Moderate)

As the disease progresses, symptoms become more pronounced:

- Increasing memory loss and confusion

- Difficulty performing familiar tasks, such as cooking or managing finances

- Problems recognizing friends and family

- Changes in mood, including irritability, anxiety, or depression

- Sleep disturbances and wandering behavior

This is usually the longest stage, lasting several years, and often places immense strain on caregivers.

Late Stage (Severe)

In the final stage, Alzheimer’s strips away the ability to communicate, walk, and even swallow. Symptoms include:

- Severe memory loss, including failure to recognize close family

- Loss of speech or limited words

- Inability to care for oneself

- Loss of physical functions, such as mobility and continence

At this stage, individuals require round-the-clock care. The disease becomes not just a neurological condition but a full-body challenge, often leading to infections or complications that cause death.

How Alzheimer’s is Diagnosed

There is no single test for Alzheimer’s disease. Diagnosis involves a careful process of evaluation, combining medical history, physical exams, cognitive tests, brain imaging, and sometimes laboratory tests. The goal is not only to identify Alzheimer’s but also to rule out other causes of memory loss, such as vitamin deficiencies, thyroid disorders, or medication side effects.

Medical History and Cognitive Assessments

Doctors begin by reviewing a patient’s history of symptoms, family background, and overall health. Cognitive tests, such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), measure memory, problem-solving, language, and attention.

Neurological and Physical Exams

A physical exam checks reflexes, coordination, vision, and balance, while neurological exams help rule out other brain conditions.

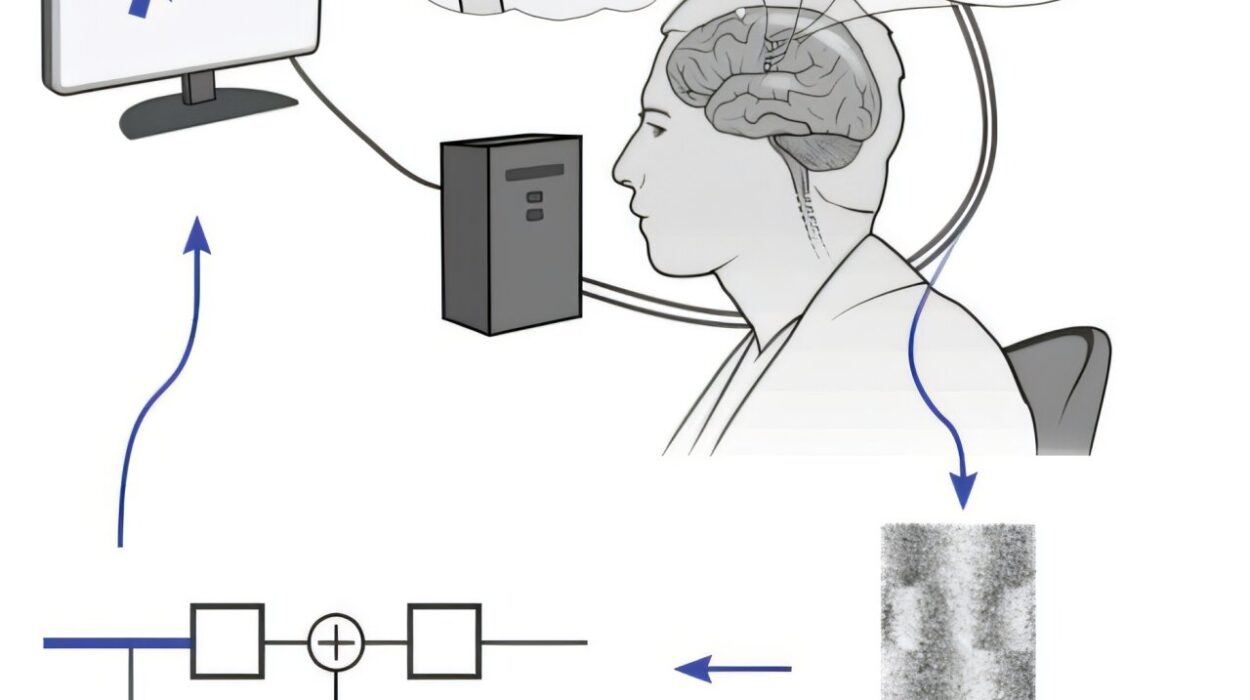

Brain Imaging

Brain scans are increasingly vital tools. MRI and CT scans can reveal brain shrinkage, strokes, or tumors, while PET scans can detect amyloid plaques and tau tangles, offering more definitive evidence of Alzheimer’s.

Laboratory Tests

Blood tests help rule out other conditions and, in some cases, detect biomarkers associated with Alzheimer’s. Emerging research is exploring blood tests that may one day allow earlier and more accurate diagnosis.

Treatment Options for Alzheimer’s Disease

Currently, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. Treatments aim to slow progression, manage symptoms, and improve quality of life.

Medications

Two main types of drugs are approved for treating cognitive symptoms:

- Cholinesterase inhibitors (donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine): These boost acetylcholine levels, improving communication between neurons. They may help with memory and attention in early to moderate stages.

- Memantine: Regulates glutamate activity, protecting neurons from overstimulation. Often used in moderate to severe cases.

Newer drugs, such as aducanumab and lecanemab, target amyloid plaques directly. These treatments represent a new era of disease-modifying therapy, though their effectiveness and availability remain under study.

Lifestyle and Supportive Therapies

Non-drug approaches are crucial in managing Alzheimer’s. Regular physical activity, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation (puzzles, reading, learning new skills) can help maintain function longer. Music therapy, art activities, and reminiscence therapy also bring comfort and joy.

Managing Behavioral Symptoms

Anxiety, agitation, aggression, and depression are common in Alzheimer’s. Counseling, structured routines, and caregiver support help reduce stress. When necessary, medications such as antidepressants or antipsychotics are used carefully under medical supervision.

Caregiving and Support

Alzheimer’s is not just a disease of the individual but of the family. Caregiving demands patience, resilience, and often sacrifice. Support groups, respite care, and counseling services are lifelines for caregivers who might otherwise face burnout.

Living with Alzheimer’s: Beyond the Clinical View

While science explains Alzheimer’s in terms of plaques and tangles, living with the disease reveals a different reality: the human experience of memory loss. Individuals with Alzheimer’s often describe feeling lost in their own homes or frustrated by their inability to express thoughts. Families experience grief, not only at the eventual loss but also at the gradual fading of the person they once knew.

Yet, amid the struggle, there are moments of light. Many families discover new ways of connecting—through music, touch, or shared silence. Some patients maintain humor, creativity, and love long into the illness. These moments remind us that Alzheimer’s, though devastating, does not erase the human spirit.

The Future of Alzheimer’s Research

Research into Alzheimer’s disease is advancing rapidly. Scientists are exploring:

- Biomarkers: Blood tests and spinal fluid markers for earlier detection.

- Genetic therapies: Targeting specific genes to reduce risk.

- Immunotherapy: Harnessing the immune system to clear plaques.

- Lifestyle interventions: Large-scale studies on diet, exercise, and brain training.

While a cure remains elusive, hope is alive. Each discovery brings us closer to a future where Alzheimer’s can be prevented, slowed, or even reversed.

Conclusion: Holding on to Hope

Alzheimer’s disease is one of humanity’s greatest medical and emotional challenges. It slowly erases memories, but it also tests the resilience of families and communities. The causes are complex, the symptoms heartbreaking, and the treatments limited—but research and compassion continue to light the path forward.

To understand Alzheimer’s is not only to study a disease of the brain but also to confront profound questions about identity, memory, and what it means to be human. And though science may one day defeat Alzheimer’s, the love, patience, and humanity of caregivers already offer the most powerful treatment: the assurance that even as memories fade, dignity and connection endure.