In recent years, the quiet resurgence of psychedelics in clinical psychiatry has drawn increasing interest from researchers, therapists, and the public alike. One compound, psilocybin—derived from so-called “magic mushrooms”—has been catapulted into the spotlight for its striking effects on treatment-resistant depression. A new open-label study, published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, adds to this growing narrative, reporting significant reductions in depressive symptoms following a single psilocybin dose in patients unresponsive to conventional treatments. This study represents not just a clinical data point, but a glimpse into a potentially transformative paradigm in mental health care.

Psilocybin: From Ancient Ritual to Modern Science

Psilocybin is far from a novel substance. For centuries, it has occupied a central role in spiritual and religious practices among Indigenous cultures in Mesoamerica. Consumed in the form of mushrooms, it was seen as a gateway to the divine, a sacrament that could reveal profound insight and healing. Only in the past few decades has science begun to rediscover what ancient societies intuitively knew: psilocybin changes minds—literally and figuratively.

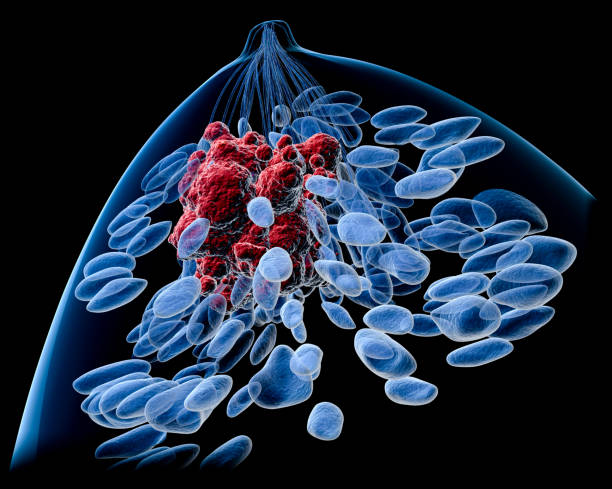

Chemically, psilocybin itself is a prodrug, meaning it becomes pharmacologically active only after the body converts it into psilocin. Once metabolized, psilocin interacts with serotonin receptors, particularly the 5-HT2A subtype. This biochemical tango is believed to disrupt default brain networks, allowing for unusual patterns of neural communication. The result? Heightened sensory perception, altered consciousness, emotional breakthroughs, and potentially, profound therapeutic benefit.

A Closer Look at the Study

Dr. Scott T. Aaronson and colleagues sought to test psilocybin’s ability to reach where conventional antidepressants fail. The study focused on a particularly challenging demographic: patients suffering from severe treatment-resistant depression (TRD)—a condition defined by the failure to respond to at least two antidepressant treatments of adequate dosage and duration. In this study, participants had undergone at least five prior failed treatments, emphasizing the gravity of their condition.

Out of over 200 individuals screened, only 12 met the strict criteria and enrolled. These participants represented an even split of men and women, with an average age of around 41. Notably, nearly half also suffered from comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a detail that would later influence treatment outcomes.

Each participant received a single 25-milligram oral dose of a synthetic version of psilocybin known as COMP360, accompanied by psychological support throughout the process. The goal was to observe whether one carefully monitored psychedelic experience could reshape the contours of deeply entrenched depression.

Measuring Change: Numbers That Tell a Story

To quantify changes in mental health, the researchers relied on several standardized assessments. Chief among them was the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), administered by clinicians at multiple intervals: before the treatment, and again one, three, and twelve weeks after the psilocybin session. Participants also self-reported their perceived quality of life and anxiety levels using validated scales.

The results were immediate and striking. Within just one week, depression scores had plummeted. By the third week, although there was a modest increase in symptoms, the scores remained significantly lower than baseline. At the twelve-week mark, some of this temporary rebound had dissipated, and depressive symptoms dipped again. In several cases, the improvements were dramatic and sustained.

However, the picture was not universally rosy. Individuals with co-occurring PTSD appeared to benefit less. For them, the therapeutic effects were weaker and less enduring. While the sample size was too small for definitive conclusions, this observation opens up critical questions about how different psychiatric conditions may interact with psychedelic treatments.

The Power and the Limits of Psychedelic Therapy

The study provides early, tantalizing evidence that psilocybin-assisted therapy may be safe, tolerable, and effective—at least in the short term—for individuals with depression that resists traditional treatments. What makes this finding so compelling is that it speaks to a core hope in psychiatry: that a single transformative experience, catalyzed by a psychedelic, could shortcut months or years of pharmacological trial and error.

But even as we lean into the promise, the study’s limitations are impossible to ignore. First and foremost, it was an open-label trial, meaning both the participants and the researchers knew exactly what was being administered. In such settings, placebo effects and expectancy biases can loom large. Could participants have improved partly because they believed they would? Could the therapeutic setting, the preparation, and the attention they received from clinicians have played a role independent of the compound?

Moreover, the study lacked a control group, which is crucial for determining whether the results stemmed from the drug itself or from other factors. There’s also the issue of subjectivity—while clinician-administered scales like the MADRS are standardized, they still depend on human interpretation, and the same applies to self-reported quality of life and anxiety levels.

Additionally, while psilocybin is generally physiologically safe, it’s not without risks. In some individuals, the psychedelic experience can induce intense anxiety, confusion, or re-traumatization, particularly when not carefully supported. The careful therapeutic framework used in this study was key to minimizing those risks—but it also complicates scalability.

Depression and the Unmet Need for Innovation

The need for novel approaches in depression treatment cannot be overstated. An estimated 280 million people worldwide suffer from depression, and of those, up to 55% may be treatment-resistant. The personal cost—loss of hope, relationships, productivity, even life itself—is staggering. The economic burden on healthcare systems is equally massive. Traditional antidepressants like SSRIs and SNRIs have helped many, but they take time to work, and their efficacy is often incomplete.

In contrast, psychedelic-assisted therapies are beginning to chart a new path. Rather than requiring daily pills for years, they propose that a handful of guided experiences, combined with integration therapy, can catalyze enduring psychological change. The mechanism is still being explored, but it’s increasingly clear that psychedelics operate differently—not merely muting symptoms, but potentially restructuring core emotional and cognitive processes.

The Road Ahead: Questions That Demand Answers

While the study by Aaronson and colleagues adds to the excitement surrounding psilocybin, it is also a call to action for more rigorous research. Can the antidepressant effects be maintained or even enhanced with booster sessions? Would a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study yield similar results? What role does the therapeutic context play, and how can we ensure it’s preserved as treatments scale?

Another key question revolves around patient selection. As observed, individuals with PTSD experienced weaker responses. Might these individuals require different preparatory protocols, or perhaps different doses altogether? Could psilocybin be more effective in combination with other treatments? And what about safety—how do we protect vulnerable populations while expanding access?

Legal barriers, too, remain a significant hurdle. In many countries, psilocybin is still a Schedule I substance, categorized as having no accepted medical use. While clinical research is accelerating and public sentiment is shifting, the path to legalization and widespread adoption is still in its early stages.

A Quiet Revolution in Psychiatry

The findings from this small but impactful study are part of a broader movement that seeks to reimagine mental health care—not just by introducing new drugs, but by rethinking the very nature of healing. Psilocybin is not a magic bullet, but it may be a powerful catalyst. For those who have walked the long, dark corridors of treatment-resistant depression, even a glimmer of light can make a world of difference.

As science continues to explore these psychedelic frontiers, the challenge will be to maintain both rigor and reverence. Rigor, to ensure that we are guided by data, not hype. Reverence, to respect the profound nature of these experiences and the vulnerable individuals who seek them out. If balanced well, the result could be nothing less than a revolution in psychiatric care—one that heals not just the mind, but the whole person.