Beneath the familiar geography printed on world maps lies another Earth—older, fragmented, and largely invisible. It is an Earth shaped by slow tectonic drift, rising and falling seas, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the long, patient erosion of time. Continents have broken apart and collided. Coastlines have drowned and re-emerged. Human cities have flourished, vanished, and slipped beneath the waves. For centuries, stories of lost lands and sunken civilizations were dismissed as myths or exaggerations. Today, however, modern geology, oceanography, archaeology, and satellite imaging are revealing that many of these stories are rooted in physical reality.

Scientists now study submerged continents and drowned cities not as legends, but as data-rich records of Earth’s dynamic history. These hidden worlds help explain plate tectonics, climate change, sea-level rise, and human adaptation. They remind us that the surface of our planet is not fixed, and that what we consider permanent is often temporary on geological timescales. The following seven hidden continents and sunken cities represent some of the most compelling cases where science is reshaping our understanding of the planet’s past.

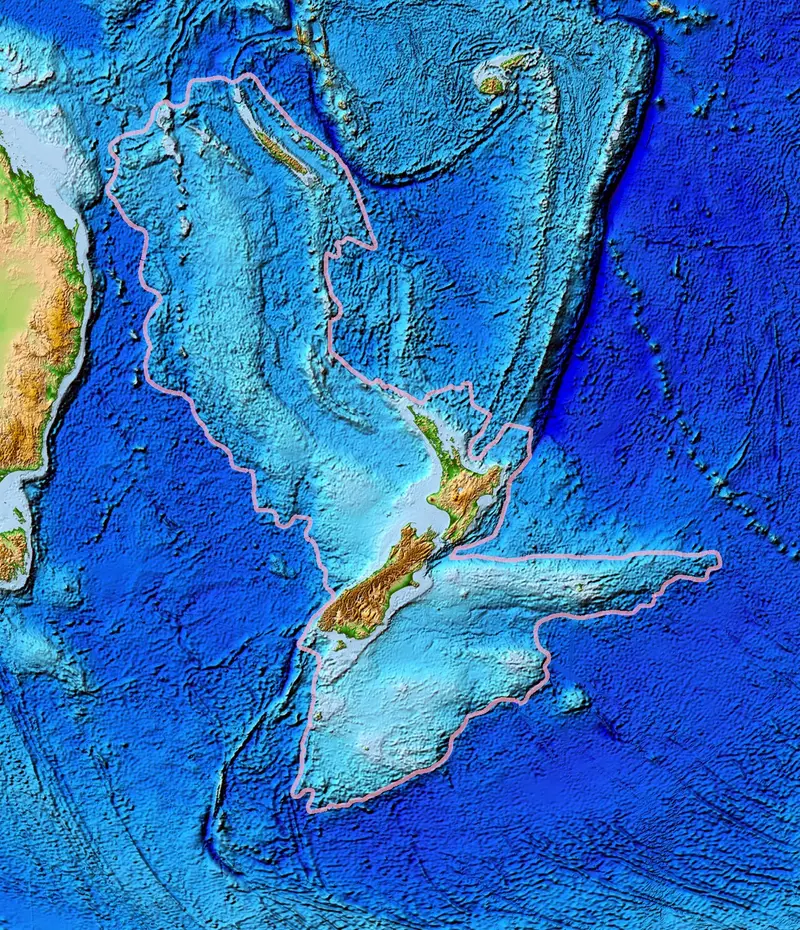

1. Zealandia: Earth’s Nearly Forgotten Continent

For most of modern history, the idea that Earth had undiscovered continents seemed impossible. Yet in the early twenty-first century, geologists confirmed that Zealandia meets the scientific criteria of a continent, even though nearly 94 percent of it lies submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean. Stretching from New Zealand to New Caledonia, Zealandia covers an area roughly two-thirds the size of Australia.

What makes Zealandia scientifically remarkable is not just its size, but its geological coherence. Continental crust is thicker and less dense than oceanic crust, and Zealandia possesses this characteristic continental structure across a vast region. Rock samples, seismic data, and gravitational measurements all show that Zealandia is not a scattering of islands, but a single, unified landmass that slowly sank after breaking away from the ancient supercontinent Gondwana tens of millions of years ago.

The submergence of Zealandia was not sudden or catastrophic. Instead, it reflects the slow stretching and thinning of continental crust, combined with rising sea levels. This gradual drowning preserved geological features that would have been erased by erosion had the land remained above water. As a result, Zealandia offers scientists a rare opportunity to study continental evolution in a relatively pristine state.

Beyond geology, Zealandia reshapes how scientists think about biodiversity. New Zealand’s unique plants and animals evolved in isolation, and understanding Zealandia helps explain how this isolation arose. Far from being an anomaly, Zealandia demonstrates that continents are not static entities. They can rise, fragment, and disappear, leaving only scattered islands as surface clues to their existence.

2. Doggerland: The Lost Heart of Northern Europe

At the end of the last Ice Age, much of what is now the North Sea was dry land. This vast region, known as Doggerland, once connected Great Britain to mainland Europe. Rivers flowed across plains, forests spread over low hills, and human communities hunted, fished, and migrated across a landscape that no longer exists.

Doggerland’s disappearance was driven by rising sea levels as glaciers melted, combined with powerful geological events such as underwater landslides and tsunamis. Over thousands of years, the sea advanced inland, fragmenting the land into islands and eventually submerging it entirely. What remains today lies beneath shallow waters, covered by sediments that preserve traces of ancient ecosystems and human activity.

Scientific interest in Doggerland intensified when fishermen began pulling stone tools, animal bones, and human artifacts from the seafloor. These accidental discoveries sparked systematic studies using sonar mapping, sediment cores, and seismic surveys originally developed for oil exploration. The result is a surprisingly detailed reconstruction of a vanished landscape.

Doggerland holds deep emotional significance because it represents a human homeland erased by environmental change. Studying it helps scientists understand how prehistoric communities responded to rising seas, offering valuable lessons for a modern world facing climate-driven sea-level rise. Doggerland is not just a geological curiosity; it is a submerged chapter of human history.

3. Sundaland: Southeast Asia’s Submerged Super-Landmass

During periods of low sea level, Southeast Asia looked radically different from today. The islands of Indonesia, Malaysia, and surrounding regions were once connected to mainland Asia in a vast landmass known as Sundaland. This region played a crucial role in human evolution and migration, acting as a corridor for early humans moving between continents.

As ice sheets melted and sea levels rose, Sundaland fragmented into thousands of islands, drowning forests, river valleys, and potential human settlements. Today, much of this lost land lies beneath shallow seas such as the Java Sea and the South China Sea. Marine sediments preserve pollen, plant remains, and river deposits that reveal a landscape once rich in biodiversity.

From a scientific perspective, Sundaland is essential for understanding how climate and sea-level changes shape ecosystems and migration patterns. Genetic studies of modern populations, combined with archaeological evidence, suggest that Sundaland influenced the distribution of species, including humans.

The emotional power of Sundaland lies in its scale. Entire ecosystems disappeared beneath the ocean, not through sudden catastrophe, but through slow, relentless change. Studying Sundaland reminds us that Earth’s geography is fluid, and that environments supporting life can vanish within the span of human memory.

4. Yonaguni Monument: Natural Formation or Sunken City?

Off the coast of Japan lies one of the most controversial underwater structures ever discovered. The Yonaguni Monument consists of massive stone terraces, sharp angles, and step-like formations that resemble monumental architecture. Since its discovery, scientists and researchers have debated whether it is a natural geological formation or the remains of a prehistoric human-built structure.

Geologists point out that the monument is carved from sandstone that fractures along straight planes, producing angular shapes through natural processes. Earthquakes and erosion could plausibly explain the stepped appearance. Archaeologists, however, note features that appear deliberately shaped, including flat platforms and possible carvings.

What makes Yonaguni scientifically valuable is not the question of its origin alone, but what it reveals about scientific method. Multiple disciplines—geology, archaeology, oceanography—converge to analyze the same evidence. Advanced mapping techniques and underwater surveys continue to refine understanding of the site.

Whether natural or artificial, Yonaguni highlights how sea-level rise can obscure or transform coastal landscapes. If human-made structures are involved, they would suggest sophisticated societies existed earlier than currently accepted. Even if entirely natural, the monument illustrates how geology can mimic human design, challenging assumptions about what we think we see.

5. Thonis-Heracleion: Egypt’s Sunken Port City

For centuries, ancient texts described a grand Egyptian port city near the mouth of the Nile, but its exact location remained unknown. Thonis-Heracleion, as it was called by Egyptians and Greeks respectively, was long considered semi-mythical. That changed when underwater archaeologists discovered its remains submerged beneath the Mediterranean Sea.

The city sank due to a combination of rising sea levels, earthquakes, and a phenomenon known as soil liquefaction, in which water-saturated ground temporarily loses strength and behaves like a fluid. Over time, massive buildings collapsed and slid into the sea, preserving statues, temples, and harbor structures beneath layers of sediment.

Excavations have revealed colossal statues, inscriptions, and shipwrecks, offering unprecedented insight into trade, religion, and daily life in ancient Egypt. Thonis-Heracleion demonstrates how coastal cities, even powerful ones, are vulnerable to geological forces.

Scientifically, the site provides a detailed case study of how natural processes can erase urban centers. Emotionally, it is a reminder of impermanence. A city that once controlled international trade and hosted grand ceremonies now lies silent beneath the waves, its story recovered piece by piece through patient scientific work.

6. Dwarka: A Legendary City Beneath the Arabian Sea

Along India’s western coast lies the ancient city of Dwarka, associated with religious texts and epic narratives. For generations, stories claimed that an ancient city had been swallowed by the sea. Modern underwater archaeology has revealed submerged structures near Dwarka, including walls, foundations, and stone blocks arranged in patterns consistent with human construction.

Scientific analysis suggests that these structures may represent multiple phases of habitation, with different settlements submerged over time as sea levels rose and coastlines shifted. Radiocarbon dating and sediment analysis help establish timelines that align with known periods of human settlement in the region.

The Dwarka discoveries sit at the intersection of science and cultural memory. While archaeology does not confirm every detail of legendary accounts, it shows that the core idea of coastal cities lost to the sea is grounded in geological reality.

From a scientific standpoint, Dwarka illustrates how oral traditions can preserve echoes of real events across millennia. Studying such sites requires careful separation of myth from evidence, but also respect for the possibility that ancient narratives encoded observations of environmental change.

7. Mauritia: The Sunken Continent Beneath the Indian Ocean

Hidden beneath the Indian Ocean lies evidence of an ancient continent known as Mauritia. Unlike Zealandia, Mauritia left few visible traces above sea level. Its existence was inferred from fragments of continental minerals, including zircon crystals, found embedded in volcanic rocks on the island of Mauritius.

These minerals are far older than the volcanic island itself, indicating that they originated from ancient continental crust that once existed in the region. Geological modeling suggests that Mauritia was part of a larger landmass that fragmented during the breakup of supercontinents, leaving isolated continental fragments submerged beneath oceanic crust.

Mauritia challenges traditional definitions of continents and highlights the complexity of plate tectonics. It shows that continents do not always disappear cleanly. They can be stretched, thinned, and broken into pieces, some of which remain hidden beneath the ocean for hundreds of millions of years.

Emotionally, Mauritia represents the deep time of Earth’s history—a reminder that the planet’s surface has been radically reshaped long before humans existed. Studying such lost continents connects human curiosity to processes operating on timescales far beyond everyday experience.

Conclusion: Why Hidden Worlds Matter

Hidden continents and sunken cities are not curiosities tucked away in the margins of science. They are central to understanding how Earth works and how life, including human civilization, responds to change. These submerged worlds preserve records of climate shifts, tectonic movement, and cultural adaptation that cannot be found on the surface alone.

As technology improves, scientists will continue to uncover landscapes long thought lost forever. Each discovery adds depth to our understanding of the planet and reminds us that the ground beneath our feet is neither fixed nor guaranteed. In studying these hidden worlds, we are not merely uncovering the past—we are learning how fragile, dynamic, and interconnected our world truly is.