Nearly 4.5 million years ago, Earth’s neighborhood in space was dramatically altered by two stars—a pair that brushed dangerously close to our sun. Their brief, yet intense encounter left a mark, much like the lingering scent of perfume in a room long after the person has departed. This cosmic event has finally been pieced together by a team of scientists, offering new insight into the mysteries of our solar system’s surroundings.

Led by Michael Shull, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder, the new research uncovers the profound impact of these distant stars on the clouds of gas and dust that swirl just beyond our solar system. This discovery, published on November 24 in The Astrophysical Journal, reveals how a close flyby by two hot, radiant stars likely helped shape the environment that would eventually influence life on Earth.

The Local Interstellar Clouds: A Mysterious Neighbourhood

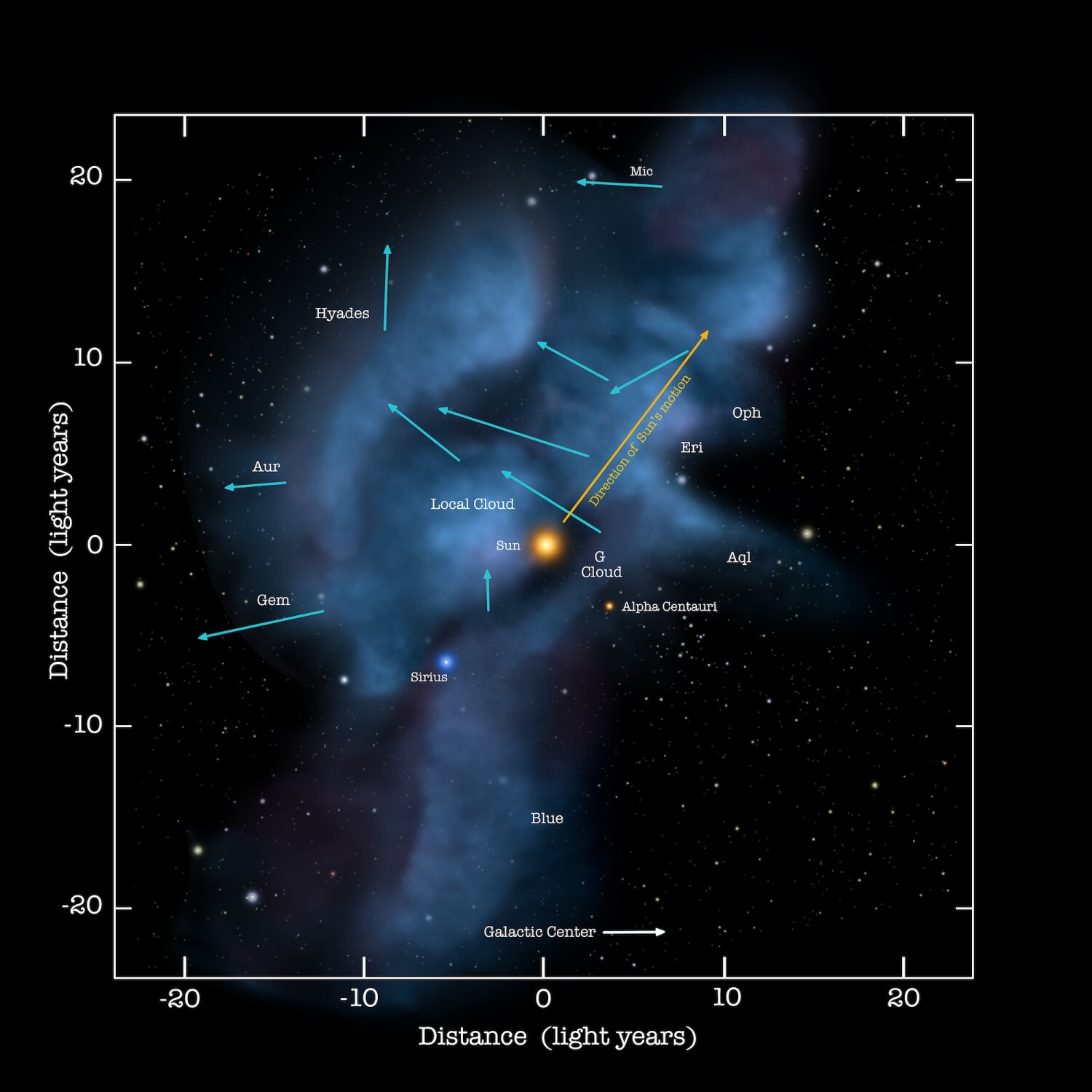

Earth exists in a special region of space, surrounded by what scientists call the “local interstellar clouds.” These clouds, made up primarily of hydrogen and helium atoms, stretch across a vast expanse of roughly 30 light-years—about 175 trillion miles—forming a unique cosmic bubble around our solar system. These clouds are not static; they drift and shift over time, interacting with our sun and other stars in the neighborhood.

In a nearby but distinct region of space, our sun resides within the “local hot bubble”—a sparsely populated area where gas and dust are relatively scarce. Yet, despite the emptiness of this bubble, the local clouds are still rich with information, and their study is key to understanding how life on Earth might have evolved. According to Shull, these clouds might have played a critical role in shielding our planet from harmful radiation, possibly making Earth the hospitable home it is today.

“The fact that the sun is inside this set of clouds that can shield us from that ionizing radiation may be an important piece of what makes Earth habitable today,” said Shull, professor emeritus in the Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences at CU Boulder.

But how did these clouds become ionized, and why does that matter?

Stars in the Spotlight

To solve the puzzle of the ionized local clouds, Shull and his team turned to a pair of stars: Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris. Located in the constellation Canis Major, these two stars are often referred to as the “Great Dog” stars. They sit far from Earth—more than 400 light-years away—but their influence reaches across space.

Based on the team’s calculations, these two massive, hot stars passed by our sun around 4.4 million years ago, within a close distance of 30 to 35 light-years. In cosmic terms, this was an incredibly close encounter. These stars, much hotter than our sun, radiated intense ultraviolet light, which played a pivotal role in ionizing the surrounding gas clouds. This radiation stripped electrons from hydrogen and helium atoms, leaving behind positively charged ions that can still be detected today.

“If you think back 4.4 million years, these two stars would have been anywhere from four to six times brighter than Sirius is today, far and away the brightest stars in the sky,” Shull explained.

The team’s research provides a deeper understanding of the processes that led to the ionization of the clouds surrounding our solar system. It suggests that Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris were not the only culprits. A combination of other celestial phenomena, including supernovae and the heat from the local hot bubble, all contributed to the charged state of these clouds.

Unraveling the Mystery of Ionization

The ionization of the local clouds had puzzled scientists for decades. When astronomers first studied this region of space using telescopes, such as the Hubble Space Telescope, they discovered an anomaly: a significant portion of the hydrogen and helium atoms in the clouds had been ionized, with helium undergoing a particularly high level of ionization. What caused this unusual phenomenon?

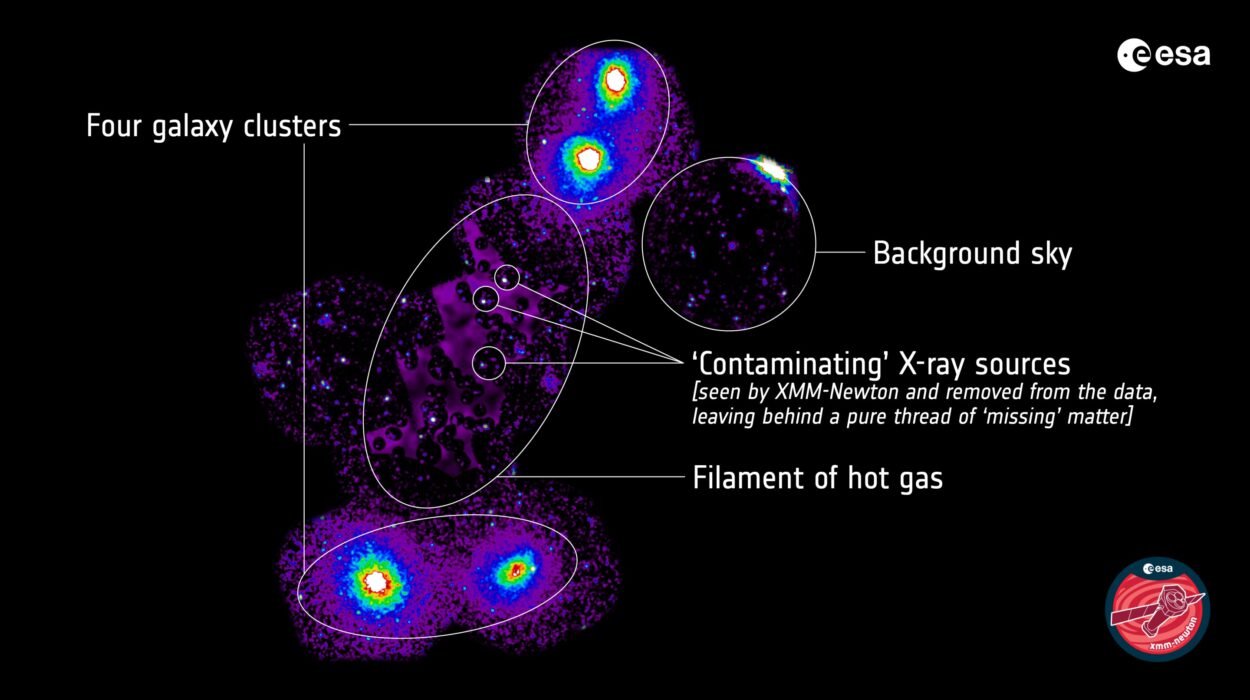

Shull and his team modeled the conditions of Earth’s cosmic neighborhood millions of years ago, carefully factoring in the movement of the sun, the stars, and the local gas clouds. As they pieced together the movements of stars and gases, they found that at least six sources contributed to the ionization of the clouds. In addition to the two stars, three white dwarf stars, as well as the energetic radiation emanating from the local hot bubble, played a role. This bubble, created by a series of supernova explosions over millions of years, is a void in space filled with hot gases that continue to emit ultraviolet and X-ray radiation, further ionizing the surrounding clouds.

“It’s kind of a jigsaw puzzle where all the different pieces are moving,” Shull said. “The sun is moving. Stars are racing away from us. The clouds are drifting away.”

The Heat of the Moment

Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris, the two stars responsible for much of the ionization, are both members of a class of stars known as B-type stars. These stars are incredibly hot—around 38,000 and 45,000 degrees Fahrenheit, respectively—compared to the sun’s much cooler 10,000 degrees. The intense ultraviolet radiation from these stars was enough to strip electrons from the hydrogen and helium atoms in the local clouds, leaving a lasting mark on their composition.

These stars, however, are not destined to last forever. They live fast and burn through their fuel at an extraordinary rate, meaning they have a relatively short lifespan of about 20 million years. Shull predicts that in a few million years, these stars will go supernova, exploding in a burst of energy so bright it could light up the sky—though not in a way that would pose any danger to Earth.

“A supernova blowing up that close will light up the sky,” Shull said. “It’ll be very, very bright but far enough away that it won’t be lethal.”

Why This Matters

This research matters because it provides crucial insight into the environment of our solar system millions of years ago, offering clues about how cosmic events may have shaped the conditions necessary for life on Earth. Understanding the forces that ionized the clouds around our solar system—and the role played by nearby stars—helps scientists better grasp the processes that influence the habitability of planets.

As Shull points out, the shielding effect of these local clouds may have been an important factor in protecting Earth from harmful radiation, allowing life to evolve in a stable environment. The study also highlights the interconnectedness of stars and the complex dance that takes place in our corner of the galaxy—a dance that continues to shape our universe in ways we are only beginning to understand.

In a way, the stars Epsilon and Beta Canis Majoris have left us a cosmic fingerprint, one that not only tells the story of their brief passage through our neighborhood but also sheds light on the conditions that helped make Earth the habitable planet it is today. And as we continue to explore the far reaches of space, we may yet discover more about the forces that have shaped not only our planet but the entire universe itself.

More information: J. Michael Shull et al, Ionization Sources of the Local Interstellar Clouds: Two B Stars, Three White Dwarfs, and the Local Hot Bubble, The Astrophysical Journal (2025). DOI: 10.3847/1538-4357/ae10a6