Depression and anxiety are often described as illnesses of the mind, but what if part of the story begins in the bones of the skull itself? Recent research suggests that immune cells released from bone marrow in response to chronic stress could be powerful players in shaping mood disorders. This discovery not only challenges the traditional view of depression as a purely chemical imbalance in the brain but also opens an entirely new window into treatment possibilities for millions of people worldwide.

The findings come from a team of scientists at the University of Cambridge in the UK and the National Institute of Mental Health in the US, and they reveal an unexpected link between stress, inflammation, and emotional suffering. Their work shows how the immune system—designed to protect us—can sometimes backfire, fueling long-term sadness, anxiety, and despair.

Stress, Inflammation, and the Emotional Body

Around one billion people across the globe will be diagnosed with a mood disorder such as depression or anxiety in their lifetime. For decades, the dominant explanations focused on brain chemistry—neurotransmitters like serotonin and dopamine—and the drugs designed to boost them. But not everyone finds relief from these treatments. In fact, nearly one in three people with depression fail to respond to standard antidepressants, leaving them trapped in cycles of exhaustion, hopelessness, and social withdrawal.

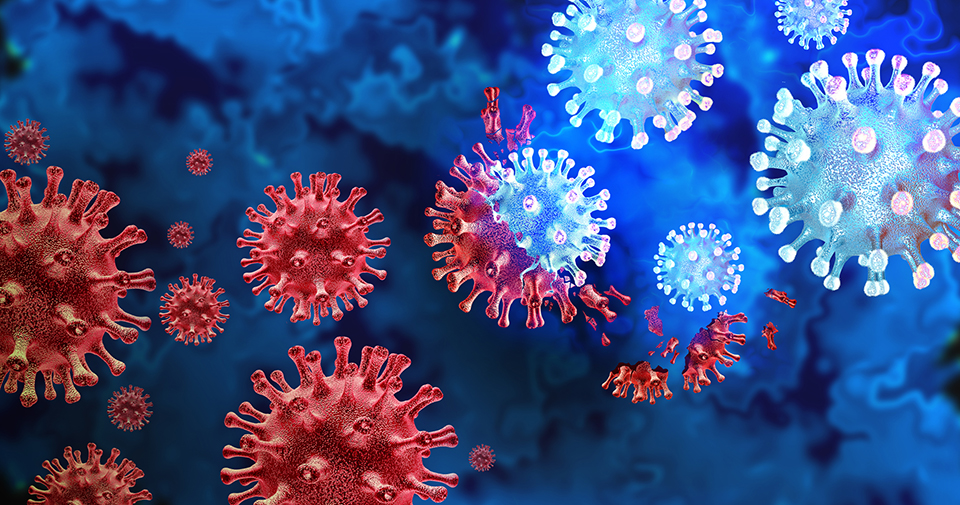

This has led scientists to search for deeper explanations. Increasingly, the immune system has come into focus. Chronic inflammation—when the body’s defenses remain on high alert even without infection or injury—has been repeatedly linked to mood disorders. It’s as if the body’s alarms are stuck in the “on” position, disrupting not only physical health but also mental well-being.

A key suspect in this story is the neutrophil, a type of white blood cell best known as the body’s “first responder.” Neutrophils are usually heroes, rushing to wounds or infections to contain damage. But in depression, researchers have noticed unusually high levels of these cells. Until recently, however, no one understood exactly how they might contribute to the emotional weight of stress.

Following the Trail of Stress in Mice

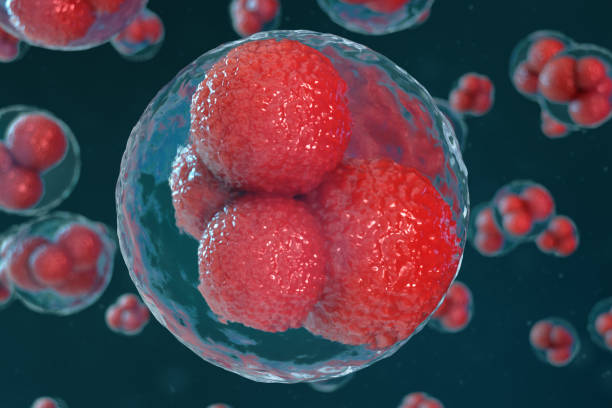

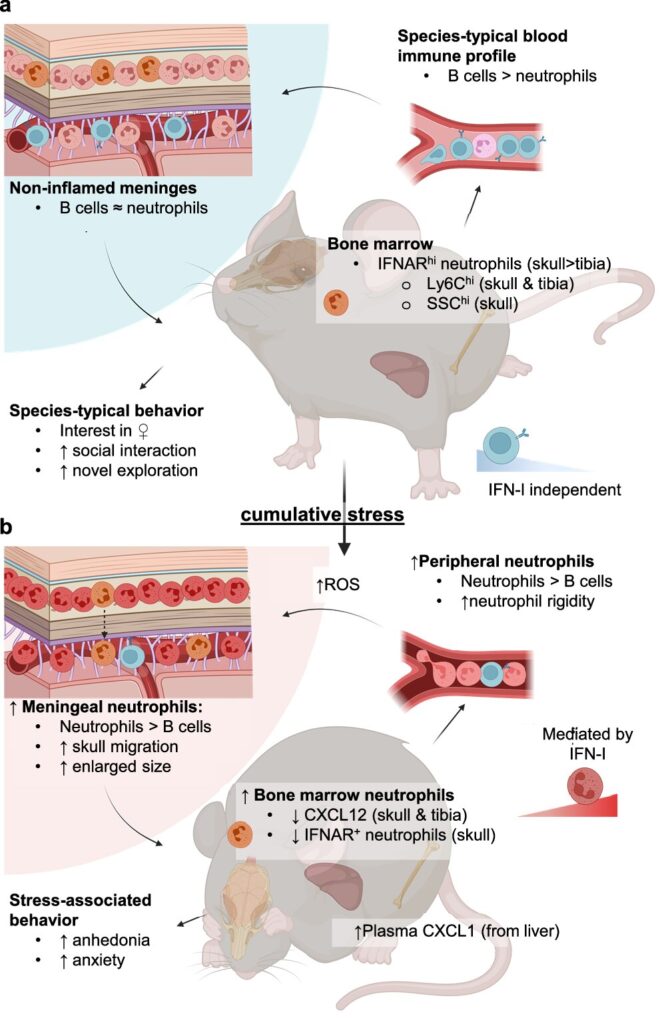

To unravel the mystery, the Cambridge and NIH team turned to animal models, since directly testing such mechanisms in humans is not possible. They exposed mice to chronic social stress—a setting where an “intruder” mouse was repeatedly placed into the territory of a more aggressive one. This kind of controlled stress mimics prolonged social adversity, a known risk factor for human depression.

The results were striking. Prolonged stress led to a surge of neutrophils in the meninges, the delicate membranes that cover the brain and spinal cord. Even more striking was that these immune cells lingered in the meninges long after stress had ended, unlike those circulating in the blood which faded more quickly. Their persistence hinted at lasting changes to the brain’s immune environment—changes that could explain why depression and anxiety sometimes linger long after stressful events are over.

When scientists traced the origin of these meningeal neutrophils, they discovered they had been released from bone marrow in the skull itself. In other words, the bones surrounding the brain were supplying immune cells that directly influenced mood and behavior.

The Immune System’s “Alarm Signal”

But what exactly were these neutrophils doing in the brain’s protective layers?

The researchers found that chronic stress triggered a molecular alarm known as type I interferon signaling within the neutrophils. Interferons are usually released when the body senses a viral infection, setting off a cascade of immune activity. But when the signal is activated inappropriately, it can lead to unnecessary inflammation.

When scientists blocked this pathway—essentially silencing the false alarm—the number of neutrophils in the meninges dropped, and the stressed mice showed improved behavior, appearing less depressed. This provided direct evidence that the immune system’s response to chronic stress was not just a side effect, but a driver of depressive symptoms.

The finding also explains why interferon-based therapies, such as those used to treat hepatitis C, often cause severe depression as a side effect. The very signaling pathway meant to protect the body from viruses may, under certain conditions, turn the mind against itself.

Why Would Neutrophils Go to the Brain?

The presence of neutrophils in the meninges raises intriguing questions. Why would immune cells that normally chase infections and wounds end up in the brain’s protective layers during stress?

One possibility is that microglia—specialized immune cells of the brain—are calling for backup when stress disturbs the brain’s equilibrium. Another explanation is that chronic stress may create microhemorrhages, tiny leaks in blood vessels, drawing neutrophils to patch the damage. But instead of helping, these cells may stiffen, get stuck, and promote inflammation, further worsening the brain’s environment.

Whatever the reason, the result is the same: an inflamed brain that struggles to maintain normal mood and emotional regulation.

Why This Matters for People With Depression

For decades, patients have been told that depression is simply the result of “low serotonin.” While this explanation has some truth, it does not capture the full picture. The immune system’s involvement reveals a more complex and holistic story—one that bridges body and mind.

This has enormous implications. If certain people’s depression is driven primarily by inflammation, then simply adjusting brain chemistry with antidepressants may never be enough. Instead, targeting the immune system—by blocking harmful signaling pathways, reducing inflammation, or even modifying bone marrow activity—could offer hope to millions who do not respond to current therapies.

It could also lead to personalized medicine. By identifying biomarkers—specific signatures in the blood or brain that indicate immune-driven depression—doctors could tailor treatments to each individual. A drug that fails in a broad trial might succeed if given to patients whose depression is specifically linked to immune dysfunction.

The Broader Links Between Immune Cells and the Mind

The research may also help explain why depression is common in neurological conditions such as stroke, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis. In these conditions, damage to the brain likely triggers immune cell activity, including neutrophil release, which in turn worsens mood and cognition.

It may even clarify why depression itself is a risk factor for dementia. If neutrophils and chronic inflammation gradually harm brain tissue, long-term depression may contribute to lasting decline in brain function.

A Human Story Beneath the Science

Beyond the technical details, this discovery carries a deeply human message. Anyone who has experienced the exhaustion of chronic stress knows how it can seep into the bones, weighing down every thought and movement. Now, scientists show that this poetic truth may be literal: the bones of the skull release immune cells that carry the burden of stress into the brain itself.

As Dr. Stacey Kigar of the University of Cambridge explained, “Our work helps explain how chronic stress can lead to lasting changes in the brain’s immune environment, potentially contributing to depression. It also opens the door to possible new treatments that target the immune system rather than just brain chemistry.”

For the millions who have tried antidepressants without relief, this research represents more than just data—it represents possibility.

Looking Ahead: Hope From the Intersection of Immunity and Mental Health

Science rarely provides immediate cures, but it offers direction. The discovery that neutrophils from skull bone marrow may help drive depression reframes how we understand mental illness. It suggests that mood disorders are not only “in the mind” but also in the immune system, in the body’s responses to stress, and in the ways our defenses can become misguided.

Future therapies may include drugs that dampen harmful immune signals, lifestyle changes that reduce chronic inflammation, or even personalized treatments based on each individual’s immune profile.

For now, the message is clear: depression is not weakness, nor a flaw in character. It is a condition rooted in biology, shaped by stress, immunity, and the profound interconnectedness of body and mind. And as science continues to peel back these layers, hope grows that new solutions will emerge—solutions that can bring light to lives dimmed by the shadows of depression.

More information: Stacey L. Kigar et al, Chronic social defeat stress induces meningeal neutrophilia via type I interferon signaling in male mice, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-62840-5