Anxiety affects millions of people around the world—so many, in fact, that it’s become one of the defining mental health challenges of our time. In the United States alone, nearly one in five adults struggles with some form of anxiety disorder. Yet despite decades of research, scientists have only begun to unravel what actually causes these feelings deep inside the brain.

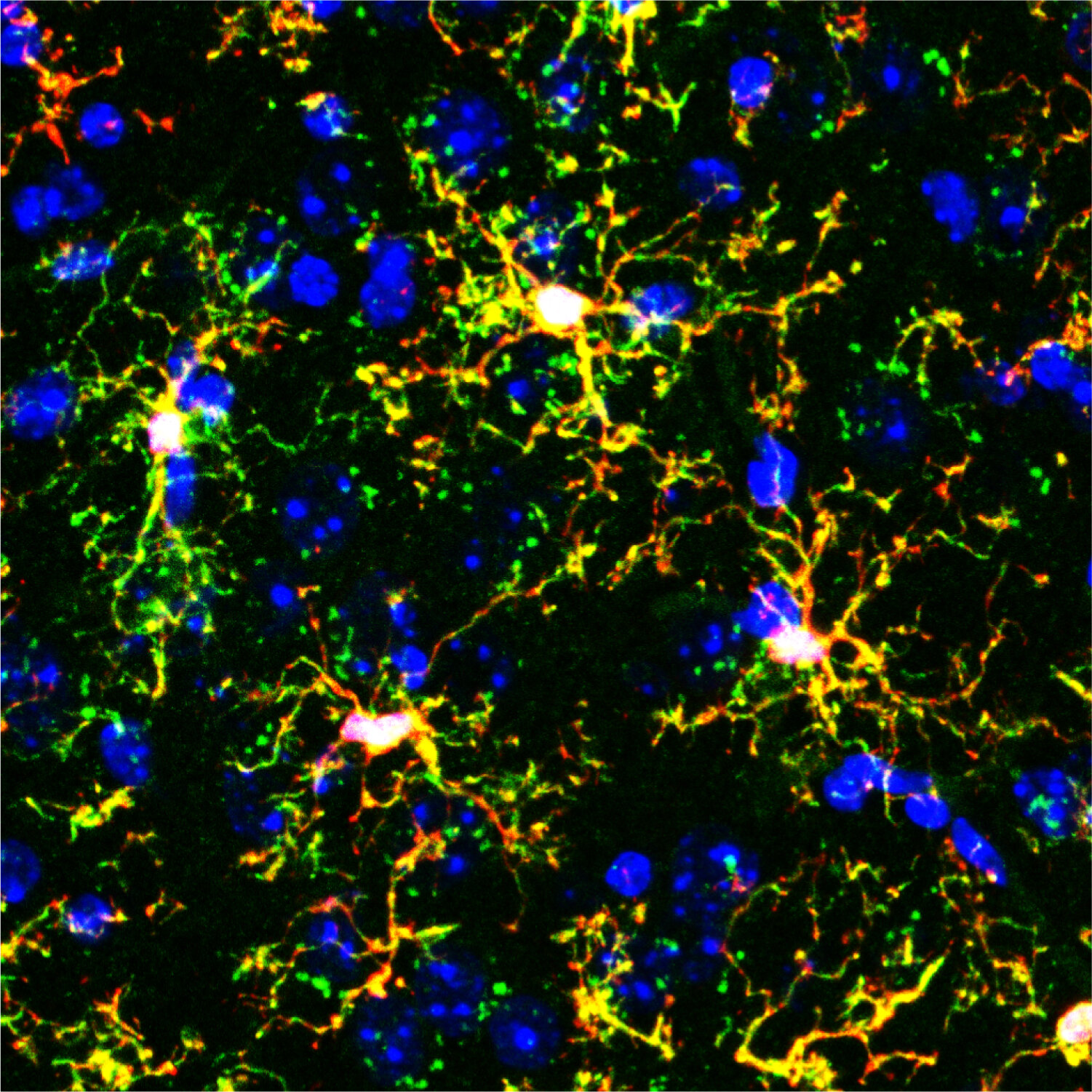

Now, a groundbreaking study from researchers at the University of Utah is reshaping what we thought we knew about anxiety. The surprising revelation? It may not be neurons—the brain’s traditional messengers—that are directly controlling how anxious we feel. Instead, the regulators of anxiety could be a completely different kind of cell: immune cells known as microglia.

This discovery marks what scientists are calling a “paradigm shift” in neuroscience. It suggests that our emotional states are not governed solely by electrical signals between neurons, but also by the health and behavior of the brain’s own immune system.

The Brain’s Immune System Steps Into the Spotlight

Microglia are small but mighty. They make up roughly 10% of all cells in the brain, constantly patrolling its terrain like tiny sentinels. Their main job is to clean up debris, fight infection, and maintain the brain’s overall health. For a long time, scientists saw them primarily as support staff—essential, but not emotional.

That perception is changing fast. Recent research has shown that microglia play active roles in shaping how neurons connect and communicate. They influence learning, memory, and now, as the University of Utah study suggests, anxiety.

The new research, published in Molecular Psychiatry, uncovers something even more remarkable: there are two distinct types of microglia that act as emotional regulators. One set serves as the brain’s “accelerator” for anxiety—ramping it up—while the other serves as the “brake,” calming it down.

“This is a paradigm shift,” says Donn Van Deren, Ph.D., who led the research during his postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Utah Health. “It shows that when the brain’s immune system has a defect and is not healthy, it can result in very specific neuropsychiatric disorders.”

A Closer Look at the Two Sides of Microglia

In earlier studies, scientists already suspected that microglia were somehow linked to anxiety. But the puzzle didn’t make sense. When researchers disrupted one specific group of microglia—known as Hoxb8 microglia—mice started to show signs of anxiety. They groomed themselves compulsively and avoided open spaces, behaviors that mirror anxious responses in humans.

Curiously, when scientists disrupted all microglia in the brain, the anxiety-like behaviors disappeared. It was as if removing both the gas and the brake at the same time brought everything back into balance.

That strange result led to a startling hypothesis: not all microglia do the same thing. Some may drive anxiety, while others suppress it.

The Experiment That Changed Everything

To test this theory, researchers performed a bold and unusual experiment. They transplanted specific types of microglia into mice that had none of their own.

When the team introduced non-Hoxb8 microglia—the suspected “accelerator cells”—the mice became anxious. They engaged in repetitive behaviors and avoided open areas, classic signs of heightened anxiety. These cells appeared to amplify emotional tension, like pressing a gas pedal to the floor with no way to stop.

But when researchers transplanted only Hoxb8 microglia, the effect was the opposite. The mice stayed calm, exploring their environment without signs of distress. And when both types of microglia were present together, anxiety levels returned to normal.

The conclusion was clear: one group of microglia promotes anxiety, and the other group prevents it. Together, they form a delicate balance that determines how the brain responds to stress and uncertainty.

“These two populations of microglia have opposite roles,” explains Mario Capecchi, Ph.D., a Nobel laureate and distinguished professor of human genetics at the University of Utah Health. “Together, they set just the right levels of anxiety in response to what is happening in the mouse’s environment.”

The Brain’s Emotional Balancing Act

This balance between Hoxb8 and non-Hoxb8 microglia may help explain why some people experience chronic anxiety while others remain resilient. If the “brake” cells are underactive or damaged, anxiety might spiral out of control. If the “accelerator” cells are overly active, even minor stress could feel overwhelming.

What’s especially profound about this discovery is that it shifts the source of anxiety from purely electrical activity in neurons to the immune ecosystem that surrounds them. It suggests that when the brain’s immune system is out of balance, emotions can become unmoored.

It’s a reminder that mental health is not just a matter of psychology—it’s biology, chemistry, and immunity intertwined.

Toward a New Generation of Anxiety Treatments

Current treatments for anxiety disorders—such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and cognitive-behavioral therapy—primarily target neurotransmitters like serotonin or dopamine, the chemical messengers between neurons. But if microglia are indeed crucial regulators of anxiety, entirely new therapeutic pathways could emerge.

“Humans also have two populations of microglia that function similarly,” says Capecchi. “This means that one day we could design drugs or therapies that specifically target these immune cells rather than neurons.”

Such treatments might work by activating the “brake” microglia or reducing the overactivity of the “accelerator” cells. They could restore emotional balance without the side effects often associated with traditional psychiatric medications.

While these possibilities are still far from clinical reality, the potential is enormous. “We’re far from the therapeutic side,” cautions Van Deren, “but in the future, one could probably target very specific immune cell populations in the brain and correct them through pharmacological or immunotherapeutic approaches. This would be a major shift in how to treat neuropsychiatric disorders.”

Rethinking the Mind–Body Connection

The idea that the immune system can shape emotions is both revolutionary and deeply human. For centuries, philosophers and scientists alike have wondered how the mind and body interact. Now, biology is revealing that the line between them is much thinner than we thought.

Microglia embody that connection. They are immune cells—traditionally seen as defenders of the body—but they also shape how we feel, think, and respond to the world. Their dual identity blurs the boundary between brain and body, emotion and immunity.

Anxiety, then, is not just a mental state. It’s an echo of a deeper biological rhythm, one that can fall out of tune when the brain’s immune cells lose their harmony.

More information: Donn A. Van Deren et al, Defective Hoxb8 microglia are causative for both chronic anxiety and pathological overgrooming in mice, Molecular Psychiatry (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41380-025-03190-y