Over the past few decades, the map of global prosperity has been dramatically redrawn. Some communities have flourished, while others have been left behind. Across the United States, the United Kingdom, and much of Europe, wealth has become increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few, leaving widening gaps between the rich and the poor.

This growing divide isn’t just about money in the bank — it’s about opportunity, access, and the hidden consequences that ripple through society. Economists often describe this gap with a single number called the Gini coefficient, where 0 represents perfect equality and 1 represents complete inequality. Many of the world’s most developed countries are now climbing dangerously high on that scale.

But beyond the economic statistics lies a deeper and more unsettling question: what does living in such unequal environments do to the human mind, especially the minds of children still in the most formative stages of life?

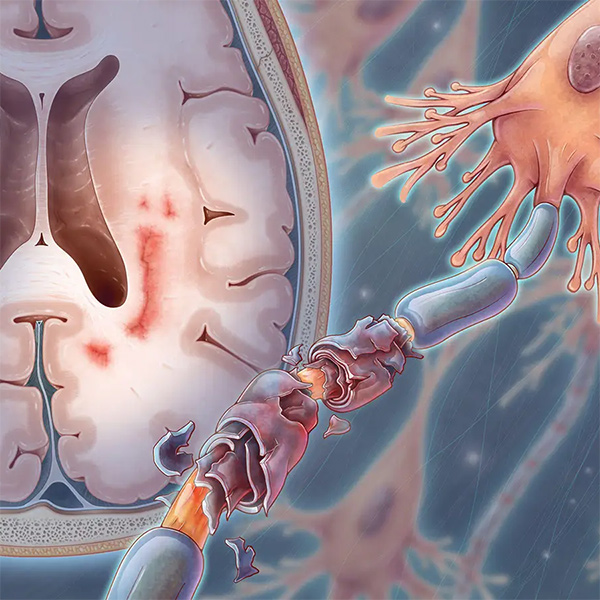

When Inequality Reaches the Brain

A groundbreaking study conducted by researchers from King’s College London, Harvard University, and the University of York has begun to uncover a sobering answer. Published in Nature Mental Health, the study suggests that the effects of wealth inequality may extend far beyond the economy — potentially reshaping the very structure of the developing brain.

Led by developmental neuroscientist Divyangana Rakesh, the research team sought to explore whether growing up in an unequal society might influence how a child’s brain develops during late childhood and early adolescence — a critical period for emotional regulation, social learning, and mental health.

“We wrote a recent conceptual review on how inequality may influence mental health,” Rakesh explained. “As a developmental cognitive neuroscientist, that made me curious about the neurobiological pathways underlying this link.”

With modern datasets and brain imaging technologies, Rakesh and her colleagues were able to move beyond theory and into concrete evidence — tracing how the shadow of inequality might physically manifest in the brains of children.

Inside the Study

The team analyzed data from over 8,000 children aged 9 to 10, spread across 17 U.S. states, using the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) dataset — one of the largest and most comprehensive child development studies ever conducted.

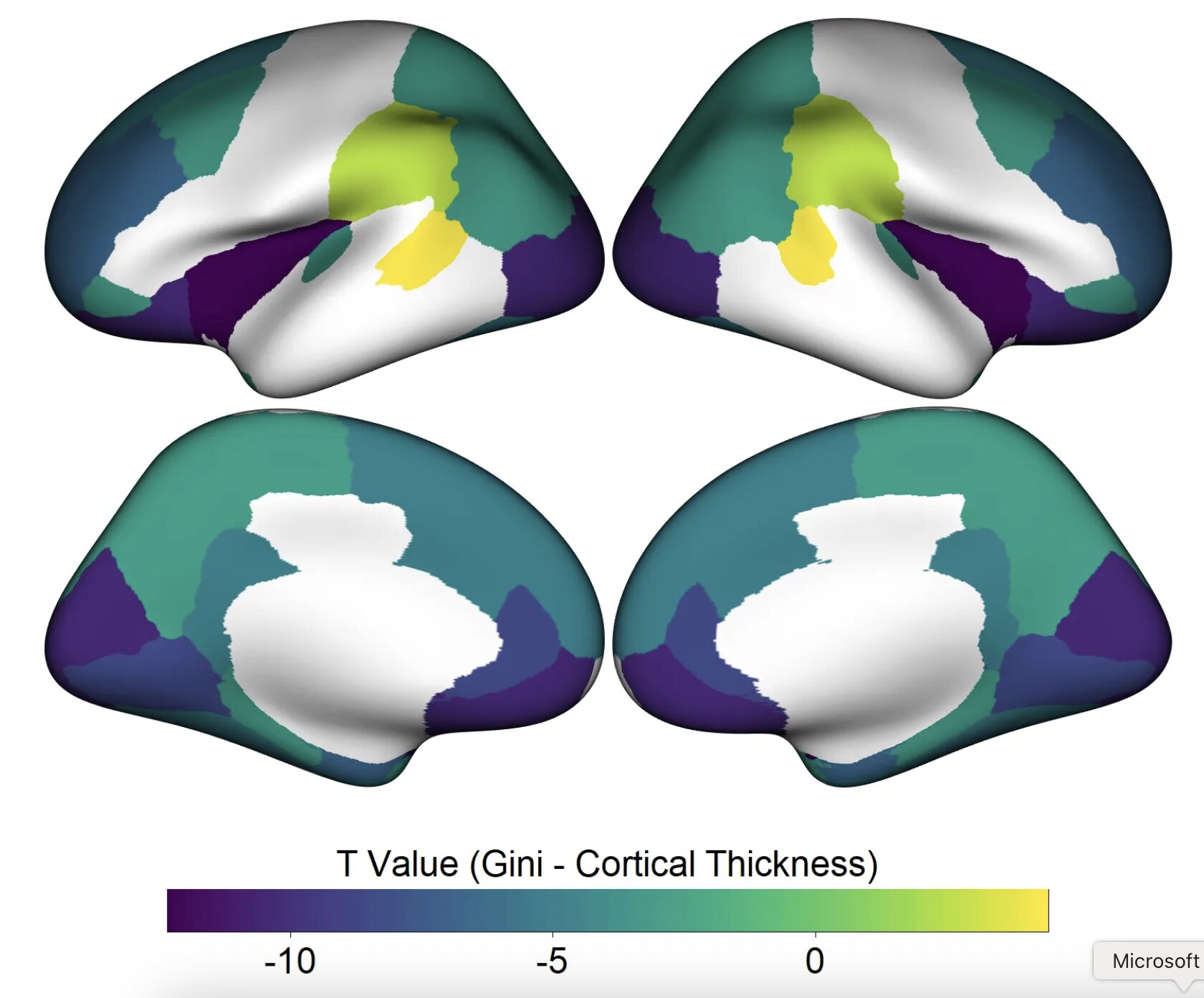

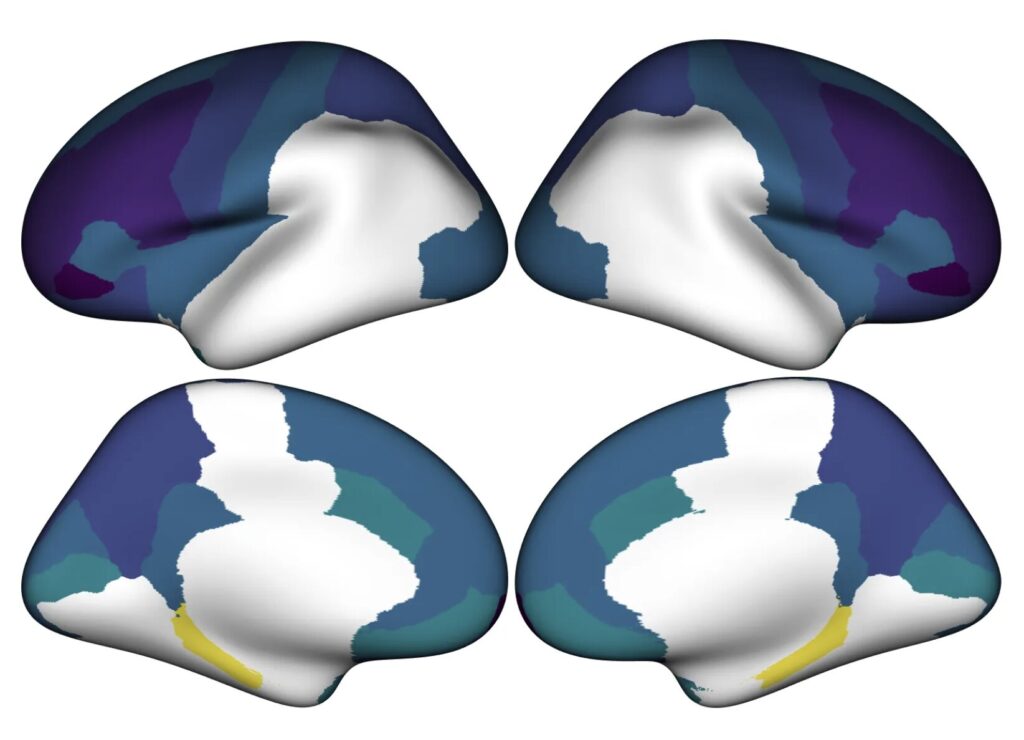

For each state, the researchers gathered Gini coefficient values, which quantified how unequal the distribution of income was in that region. They then examined MRI and fMRI brain scans from each child to measure cortical thickness, brain surface area, and the connections between twelve key brain regions involved in emotion, cognition, and self-regulation.

Importantly, the researchers controlled for multiple factors that could otherwise explain brain differences — including family income, education, healthcare access, and even incarceration rates. This ensured that what they observed was not simply a reflection of personal poverty, but of the broader social environment in which the children were growing up.

They also followed up with mental health assessments eighteen months later to see whether these early brain differences correlated with changes in emotional well-being.

The Unequal Brain

The findings were striking. Children growing up in states with higher levels of income inequality tended to have a thinner cortex — the brain’s outer layer responsible for critical thinking, decision-making, and emotional control. Some regions of the brain also showed differences in surface area, and the communication between certain networks appeared to be disrupted.

These patterns suggest that inequality itself — not just poverty — can leave measurable imprints on the developing brain.

“Our findings highlight that structural inequality, over and above family income, is associated with children’s brains,” Rakesh said.

This means that even if a child’s own family is financially stable, simply living in an environment where wealth and opportunity are unevenly distributed can subtly shape the brain’s development. The invisible psychological weight of inequality — the feeling of living in an unfair system, the stress of seeing others prosper while opportunities remain out of reach — may be biologically internalized.

From Brains to Behavior

Why does inequality affect the brain this way? Scientists believe the answer lies in chronic stress. When children are constantly exposed to environments of uncertainty, competition, or perceived disadvantage, their bodies produce elevated levels of stress hormones like cortisol. Over time, this can interfere with healthy brain development, particularly in regions involved in emotional regulation and learning.

These neurological changes may explain why inequality often correlates with higher rates of mental health disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and behavioral difficulties among children and adolescents. The brain, molded by stress and social tension, may become more reactive, less resilient, and more vulnerable to mental strain.

Rakesh and her team found that the brain differences they identified were linked to early indicators of mental health challenges in children living in more unequal states. While these findings do not imply that inequality directly causes such disorders, they reveal a strong and troubling association that deserves serious attention.

The Broader Implications

The implications of this research reach far beyond neuroscience. It challenges the notion that inequality is purely an economic or political issue — showing instead that it may have biological consequences for the next generation.

A child’s brain, shaped in part by the fairness of their environment, becomes a living record of societal structure. The study underscores that inequality is not only about who has more or less money — it’s about who has more or less opportunity to develop their full human potential.

When children grow up in societies where the gap between rich and poor feels insurmountable, it doesn’t just divide communities — it may divide minds. Inequality, in this sense, becomes a form of environmental exposure, influencing growth as surely as nutrition or education.

Rethinking Policy and Social Priorities

This research offers an urgent call to policymakers, educators, and communities. If social inequality can shape the architecture of the developing brain, then promoting greater equity isn’t just a moral imperative — it’s a biological one.

Efforts to narrow the wealth gap, improve access to education and healthcare, and reduce social stressors could yield benefits far beyond economics. They could help safeguard mental health, strengthen resilience, and ensure that every child — regardless of where they are born — can reach their full cognitive and emotional potential.

Future research, as Rakesh notes, will expand beyond the United States to include data from the UK and other countries, helping to determine whether these patterns are universal or culturally specific. Longitudinal studies will also track how inequality influences brain development over time, potentially shaping adult behavior, career paths, and even civic engagement.

The Invisible Imprint of Society

We often imagine inequality as an abstract statistic — a percentage in a report, a graph showing rising lines of disparity. But this study reveals something much more intimate: inequality lives inside us. It is etched into neural pathways, influencing how children think, feel, and relate to the world.

A society’s economic structure, it seems, doesn’t just shape its skyline or social order; it shapes its people at the most fundamental biological level. The brain — that delicate organ of hope, creativity, and empathy — may carry the fingerprints of social injustice.

A Call for Empathy and Action

Science has always shown that early life experiences leave lasting marks. Now we know that societal conditions — the very fabric of our economic and social systems — can also leave their trace in the brain. The story of inequality is not only about dollars or policies; it is about neurons and synapses, about the children whose minds reflect the fairness or unfairness of the world around them.

As societies grapple with rising divides, studies like this remind us of a deeper truth: we cannot build healthy minds in a sick society. Prosperity that is not shared becomes a burden on collective well-being.

If we wish for a future filled with empathy, intelligence, and emotional strength, we must nurture not only our children, but the fairness of the world they grow up in. Because the brain, after all, is not just a personal organ — it is a social one.

The Biology of Fairness

In the end, what this research teaches us is profoundly simple yet revolutionary: equality is nourishment for the human mind. When societies invest in fairness, they invest in the mental and emotional health of their people. When they allow inequality to fester, the cost is not only moral or economic — it is neurological.

The human brain grows best in environments of safety, opportunity, and justice. The challenge before us is clear: to build societies that feed not only the body, but also the mind.

Because the structure of our world — the way we share its wealth and opportunities — quietly sculpts the structure of our children’s brains. And in those developing brains lies the shape of our collective future.

More information: Divyangana Rakesh et al, Macroeconomic income inequality, brain structure and function, and mental health, Nature Mental Health (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s44220-025-00508-1.