When wildfires sweep across landscapes, the devastation is obvious—forests charred, homes destroyed, and skies painted in ominous shades of gray. But behind the dramatic flames lies a quieter, more insidious threat: the air we breathe. A new study led by the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal) has found that fine particles released by wildfire smoke may be far deadlier than scientists previously believed, responsible for nearly 14 times more deaths than standard pollution models suggest.

The findings, published in The Lancet Planetary Health, highlight that mortality linked to wildfire smoke may have been underestimated by 93%. This revelation underscores not only the scale of the health crisis caused by wildfires but also the urgent need to rethink how we measure and respond to air pollution in a rapidly warming world.

What Makes Wildfire Smoke So Dangerous?

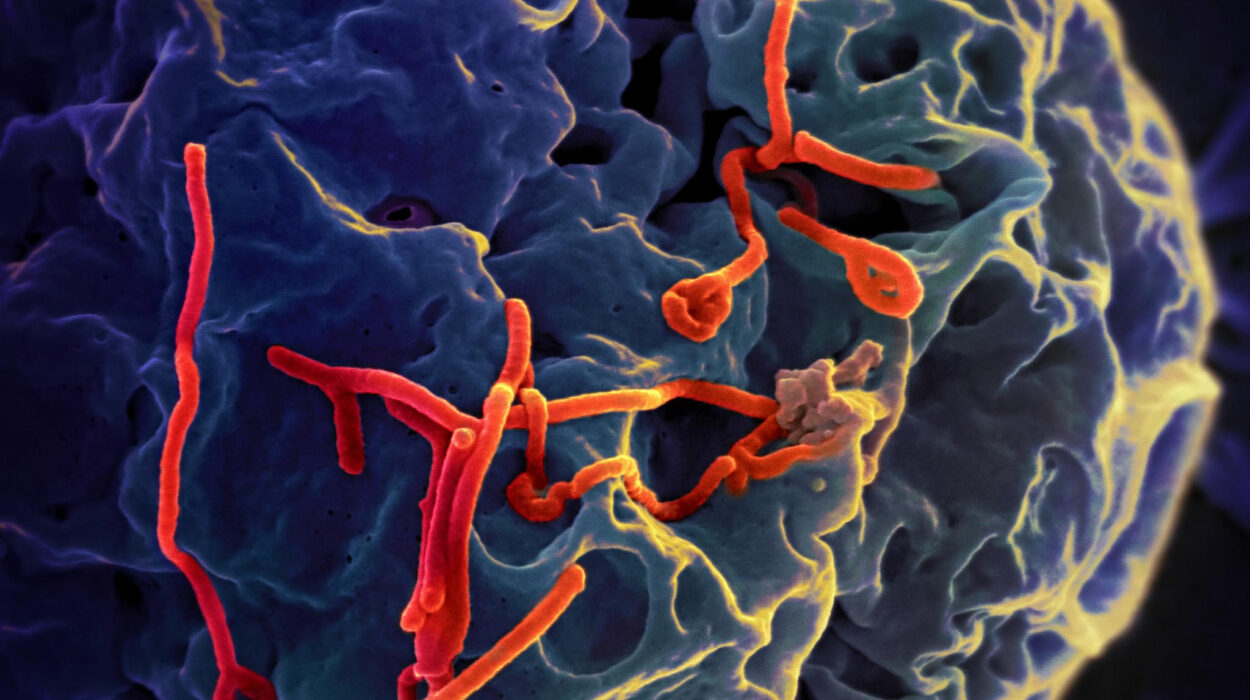

Wildfire smoke is a complex cocktail of pollutants, but at its core are fine particles known as PM2.5—tiny specks less than 2.5 micrometers wide, small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. While all PM2.5 pollution is harmful, the study provides compelling evidence that fire-derived particles carry a much higher risk of mortality than those from traffic, industry, or other sources.

The researchers found that for every tiny increase of 1 microgram per cubic meter (µg/m³) of wildfire PM2.5, there was a 0.7% rise in all-cause mortality, a 1% rise in respiratory-related deaths, and a 0.9% rise in cardiovascular deaths within just a week of exposure.

Previous research had hinted at the unique toxicity of wildfire smoke, suggesting it could be up to ten times more harmful than other particle pollution. This new analysis, covering almost two decades of data, confirms that the danger is not only real but far greater than most official estimates acknowledge.

How the Study Was Conducted

The team drew on mortality data from the EARLY-ADAPT project, which compiles daily records from 654 regions across 32 European countries, encompassing a staggering 541 million people. They paired this information with detailed estimates of daily wildfire and non-wildfire PM2.5 levels between 2004 and 2022.

Using advanced statistical models, the researchers tracked how mortality changed in the days following wildfire smoke exposure, accounting for delayed health effects. This approach provided a sharper picture of the short-term risks linked specifically to wildfire pollution.

Their results were sobering. On average, wildfire smoke was responsible for 535 deaths per year across Europe—far above the 38 deaths estimated by conventional pollution risk models. That difference represents a 93% underestimation, exposing a dangerous blind spot in public health tracking.

Regional Differences in Impact

While the overall pattern was clear—wildfire smoke kills more people than we thought—the study also revealed striking differences between regions. Countries like Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary, and Serbia showed the strongest links between wildfire PM2.5 and mortality. By contrast, parts of Portugal and Spain, despite high smoke exposure, showed weaker associations.

The reasons for this variability are not yet fully understood. The researchers suggest that factors such as wildfire management strategies, healthcare systems, and population vulnerabilities may play a role. “Possible explanations could be related to regional and national wildfire management and adaptation strategies. However, further studies are needed,” explained senior author Cathryn Tonne, an ISGlobal researcher.

Climate Change and a Future of Fire

Wildfires are not new, but climate change is making them more frequent, more intense, and more widespread. Rising temperatures, prolonged droughts, and shifting weather patterns create tinderbox conditions across Europe and beyond. As ISGlobal researcher and study lead author Anna Alari noted:

“Human-driven climate change is one of the main causes of the rising frequency and intensity of wildfires, as it creates favorable conditions for their spread and increases the number of days with very high or extremely high fire risk.”

This means that millions more people will be exposed to wildfire smoke in the coming decades. Without accurate measures of its health impacts, policymakers risk underestimating the true burden—and failing to take adequate action.

Why This Study Matters

Air pollution is already one of the world’s leading environmental killers, linked to 7 million premature deaths each year according to the World Health Organization. By revealing the underestimated toll of wildfire smoke, the ISGlobal study calls for urgent updates in how health agencies measure and respond to pollution.

Standard pollution metrics often treat all PM2.5 as the same, regardless of where it comes from. But this study demonstrates that the source of pollution matters enormously, with wildfire smoke posing a much higher risk. Without adjusting for these differences, governments may severely undercount the deaths caused by fire-driven pollution.

Protecting Public Health in the Age of Fire

The implications of this research extend beyond Europe. From California to Australia, Canada to the Amazon, wildfire smoke has become a global public health emergency. As wildfires grow in scale and intensity, the invisible fallout—tiny toxic particles carried by the wind—may kill far more people than the flames themselves.

Improved health risk estimates, better air quality monitoring, and stronger public health protections are urgently needed. Simple measures such as early warnings, smoke shelters, and promoting the use of air purifiers and protective masks during smoke events can save lives. But long-term solutions will require tackling the root cause: climate change itself.

A Warning We Cannot Ignore

The ISGlobal study sends a clear message. Wildfire smoke is not just a temporary nuisance or a seasonal inconvenience—it is a potent killer, whose impact we have gravely underestimated. In the age of climate crisis, the hidden danger drifting in the air after each fire is just as urgent as the flames on the ground.

The smoke may clear after a fire burns out, but its deadly effects linger. Recognizing and addressing this silent threat could save thousands of lives in the decades to come.

More information: Anna Alari et al, Quantifying the short-term mortality effects of wildfire smoke in Europe: a multicountry epidemiological study in 654 contiguous regions, The Lancet Planetary Health (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.lanplh.2025.101296