For thousands of years, human civilization has flourished along coastlines. Rivers and oceans have been lifelines, providing food, trade routes, and cultural connection. Today, more than two out of every five people on Earth live within 100 kilometers of the sea. But as sea levels rise and storms grow fiercer, the ancient bond between humanity and the ocean is beginning to strain.

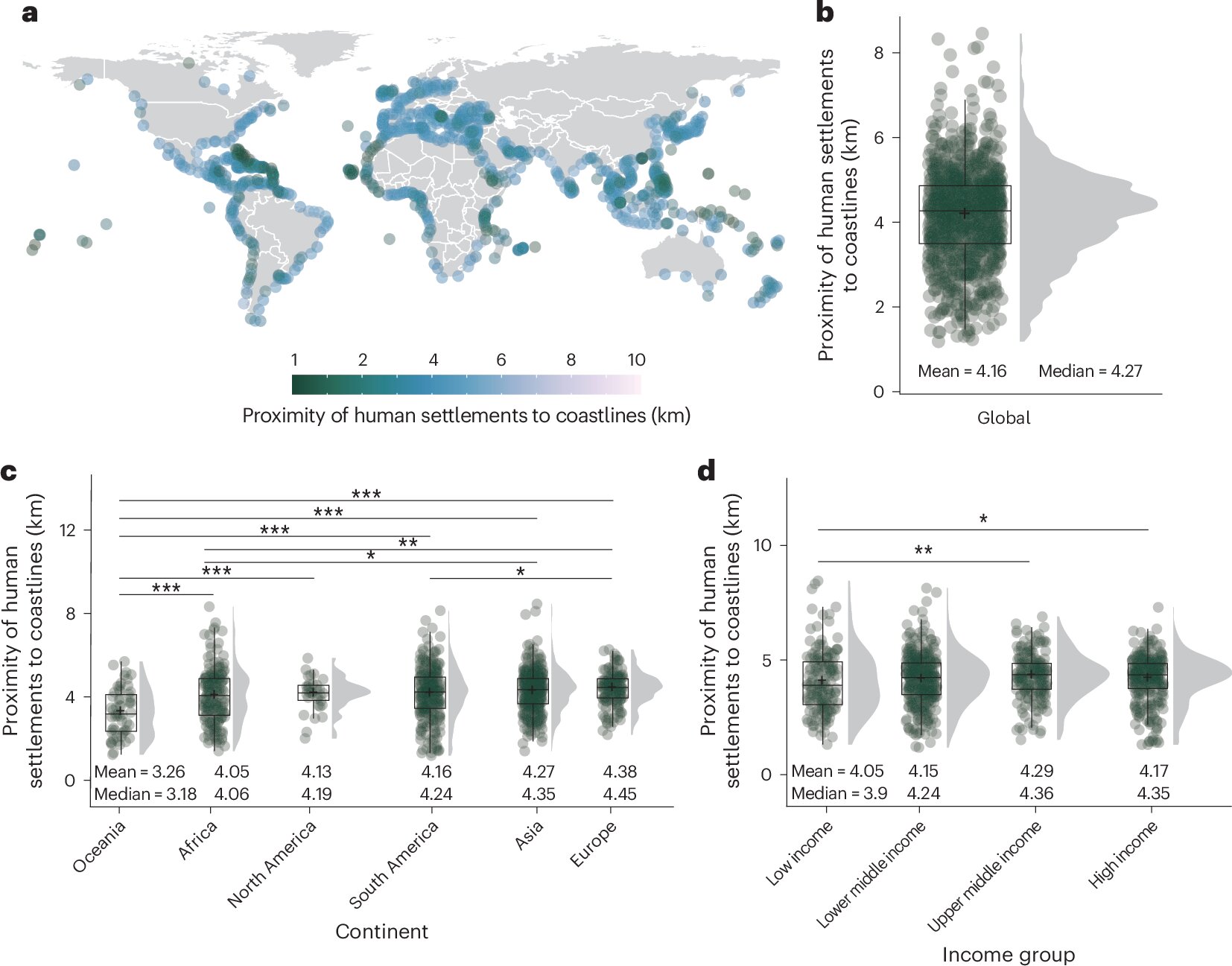

A groundbreaking international study published in Nature Climate Change has revealed a profound shift in where people live—and an even deeper divide in who gets to move and who does not. Using nearly three decades of satellite nighttime light data, researchers tracked human settlement patterns across 1,071 coastal regions in 155 countries from 1992 to 2019. Their findings highlight not only the global scale of climate-driven migration but also the stark inequalities shaping it.

A World Moving Inland—But Not Everyone Can

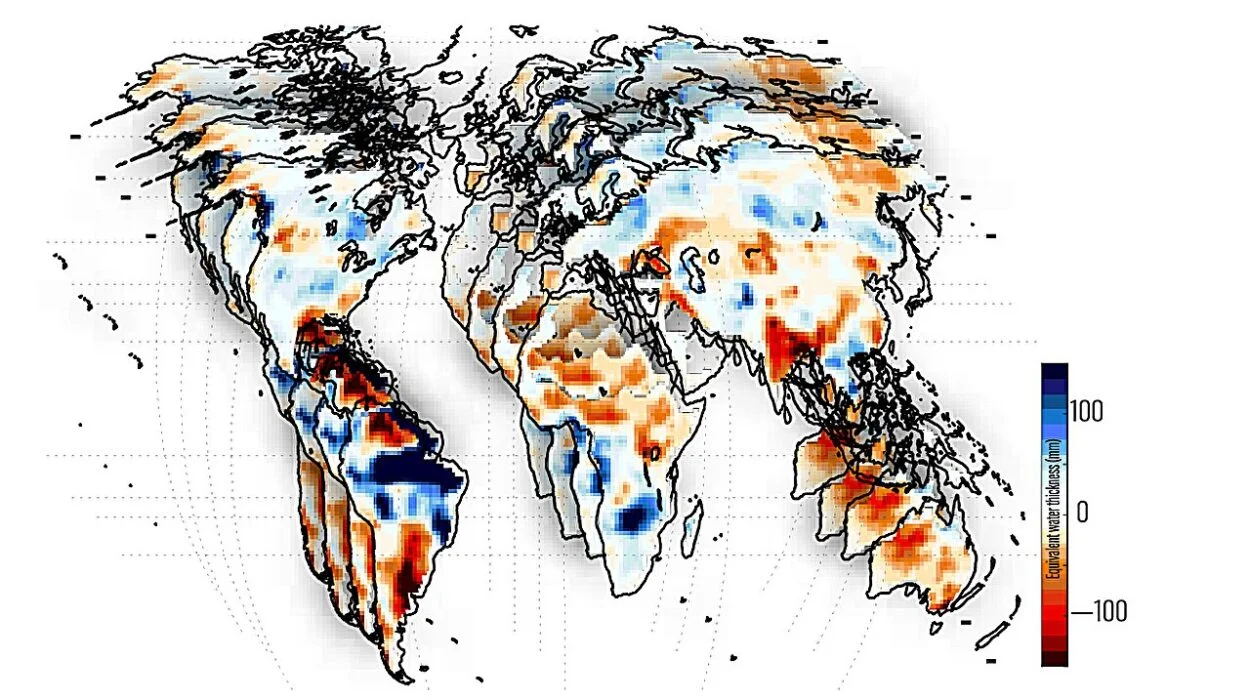

The study found that over half of the world’s coastal regions—56%—saw populations gradually shifting inland, away from the advancing threats of flooding, erosion, and sea-level rise. In many cases, this retreat reflects deliberate efforts to adapt: wealthier communities building new housing further inland, governments planning urban expansion in safer zones, or families with means choosing to move.

But the story is far from universal. Nearly a third of settlements—28%—remained in place, rooted on the coast despite worsening risks. More troubling, 16% of regions saw populations move even closer to the shoreline. And it is here that inequality becomes most visible.

The researchers found that low-income populations, lacking the resources to relocate, are being forced to stay put—or even cluster closer to coastal zones. Often this is not a matter of choice but of survival. Fishing, tourism, and port economies offer livelihoods that tether people to the sea, while the absence of affordable housing inland drives the spread of informal settlements in high-risk areas.

The Geography of Risk

The patterns of movement varied by region, painting a complex picture of climate adaptation across the globe. South America and Asia saw the strongest shifts toward coastlines, with up to 17% of populations moving closer to the sea. Europe, Oceania, Africa, and North America also showed notable coastal growth, though at slightly lower levels.

In Oceania, the relationship to the ocean runs especially deep. Many communities depend directly on the sea for cultural identity, economy, and sustenance. Here, both wealthy and poor populations often choose—or are forced—to live near the shoreline. But as Xiaoming Wang, lead author of the study and adjunct professor at Monash University, warns, this reliance leaves communities acutely vulnerable to storms, erosion, and the creeping rise of the ocean itself.

High-income regions tell another part of the story. In Europe and North America, wealth has often enabled people to remain on coastlines, supported by infrastructure such as seawalls, levees, and advanced drainage systems. But the study cautions that this reliance can breed overconfidence, encouraging further development in zones where no wall will hold back the sea forever.

Wealth, Vulnerability, and the Capacity to Move

At the heart of the research lies a stark truth: the ability to adapt is not equally distributed. Wang and his colleagues emphasize that movement away from dangerous coasts is largely driven by capacity—the financial, social, and political resources that allow relocation.

Where wealth is present, people can plan and adapt. Where poverty persists, families may find themselves trapped in harm’s way. As Wang explains, “In poorer regions, people may have to be forced to stay exposed to climate risks, either for living or no capacity to move.” The consequence is a widening adaptation gap, where those least able to protect themselves are those most at risk.

The Rising Costs of Staying Put

The risks of coastal living are no longer distant or theoretical. With each passing decade, seas inch higher, powered by melting glaciers and warming oceans. Storm surges grow stronger, swallowing entire communities in places like the Philippines, Bangladesh, and small island nations. Erosion strips away land that once seemed permanent, while saltwater seeps into freshwater reserves, threatening agriculture and drinking supplies.

For families who remain—or who move closer to the sea despite the dangers—these risks are part of daily life. Informal settlements built on floodplains or reclaimed tidal flats may be swept away in a single storm. Wealthier coastal neighborhoods are not immune either: hurricane seasons in the United States and Europe’s recent floods have shown how even the most advanced infrastructure can be overwhelmed.

Rethinking Coastal Futures

The study makes one point abundantly clear: as climate change accelerates, relocation inland will become less an option and more a necessity. But how this process unfolds will shape the social, economic, and cultural fabric of the 21st century.

Wang stresses that relocation strategies must be more than technical plans. They need to account for human lives, cultural ties, and livelihoods. Simply telling people to leave is not enough. Coastal economies must be reimagined, informal settlements improved, and vulnerable communities supported. Without these steps, the poorest will be left behind, stranded between rising seas and shrinking options.

Policy, therefore, must walk a fine line. Relocation should be balanced with investments that reduce vulnerability for those who remain—better housing, stronger early-warning systems, and sustainable livelihoods that do not demand living on the water’s edge. Coastal protection infrastructure will remain important, but it cannot be the only solution. Long-term strategies must acknowledge that no barrier can hold back the tide indefinitely.

A Shared Global Challenge

The study is the result of international collaboration, bringing together researchers from Australia, China, Denmark, and Indonesia. It is a reminder that no nation faces this challenge alone. Coastal migration, whether voluntary or forced, will ripple across borders—affecting economies, food security, and even geopolitics.

From the fishing villages of Bangladesh to the urban sprawl of Miami, from the Pacific islands to the ports of South America, humanity is in the midst of one of its greatest transformations. The question is not whether we will adapt, but how—and at what cost.

The Human Face of Relocation

Behind the statistics and maps are millions of human stories. Families rebuilding homes swept away by storm surges. Children growing up in neighborhoods where seawater floods the streets each monsoon. Entire cultures weighing the loss of ancestral lands against the need for safety. And also, wealthier communities building second homes inland, hedging their bets as seas advance.

The study forces us to confront these inequalities not as abstract data but as lived realities. Climate change is not only about the physics of rising seas—it is about justice, survival, and the choices that determine who gets to move to safety and who does not.

Conclusion: Choosing Our Future by the Water’s Edge

The world’s coastlines are shifting, and with them, the shape of human civilization. Some communities are retreating inland, others clinging to the shore, and still others moving closer to the very waters that threaten them. The pattern is uneven, driven by wealth, vulnerability, and capacity.

As sea levels rise and climate hazards intensify, relocation will increasingly define the future of coastal life. But whether this future deepens inequality or fosters resilience depends on the choices we make today.

Coastal living has always symbolized opportunity and connection. Now it also represents one of humanity’s greatest challenges. The rising tide is not just a force of nature—it is a test of our ability to adapt, to protect the vulnerable, and to build a sustainable world where no one is left behind.

More information: Lilai Xu et al, Global coastal human settlement retreat driven by vulnerability to coastal climate hazards, Nature Climate Change (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41558-025-02435-6