There are moments in life when we just click with someone—a feeling that you’re thinking the same thought before it’s spoken, that your laughter comes from the same place. We call it being on the same wavelength. It’s a poetic phrase, one that feels more spiritual than scientific. But what if that sensation wasn’t just a metaphor? What if minds, quite literally, could hum in unison?

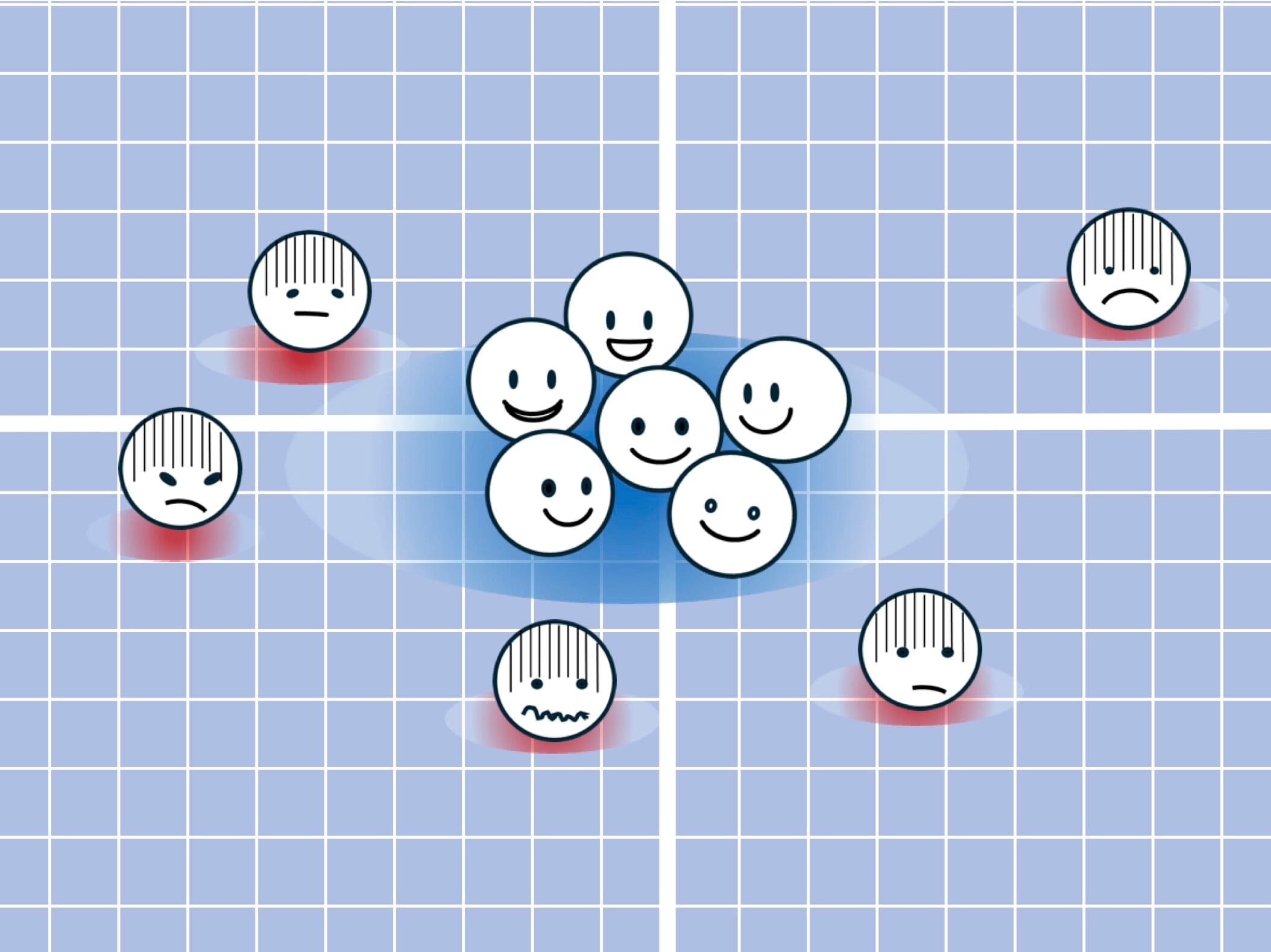

A groundbreaking study from Kobe University suggests that the minds of optimists do exactly that. When they look toward the future, their brains echo similar patterns—structured, shared, and remarkably synchronized. Meanwhile, pessimists appear to be neurological soloists, each constructing a vision of what’s to come with uniquely individual brushstrokes.

This difference isn’t just curious—it could be central to understanding human connection, communication, and why some people feel more alone in the crowd than others.

The Question That No One Had Asked

For decades, psychologists have known that optimists tend to enjoy broader social networks and report higher satisfaction in relationships. They’re often perceived as approachable, easy to understand, and emotionally uplifting. But why? What secret ingredient makes the optimist the heart of so many social circles?

Psychologist Yanagisawa Kuniaki of Kobe University had a theory. Drawing from recent discoveries in social neuroscience—where researchers found that people with similar social positions have similar brain responses—he wondered if something deeper was at play.

“If brains aligned in how they react to external stimuli,” he thought, “might they also align in how they imagine the future?”

It was a big idea. And it demanded an interdisciplinary leap that bridged the often-disconnected worlds of social psychology and neuroscience. Kuniaki and his team stepped into that unexplored territory.

They brought together a group of 87 participants, spanning the psychological spectrum from glass-half-empty to brimming-over-with-hope. Each was asked to imagine a variety of future events, both hopeful and grim, while undergoing brain scans via functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)—a technology that reveals the ebb and flow of brain activity in real time.

The goal wasn’t to measure what people said they felt—but to visualize the silent, electrical symphony playing in their heads.

A Shared Symphony of Hope

The results were both stunning and poetic.

When the optimists thought about the future, their brains lit up in a way that was strikingly similar. Across different individuals, patterns of neural activity converged—like melodies echoing the same tune in different rooms. It didn’t matter who the person was; if they were optimistic, their brain followed the same kind of rhythm when envisioning what might come next.

Pessimists, however, were a different story. Their neural responses were wildly diverse. While one might imagine a bleak job interview and another an uncertain medical diagnosis, their brain patterns danced to different beats. It was as if each was composing their own song—complex, unpredictable, and entirely personal.

This divergence gave rise to one of the most elegant metaphors in modern neuroscience, drawn from literature. Echoing the opening line of Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, the researchers summarized: “Optimistic individuals are all alike, but each less optimistic individual imagines the future in their own way.”

For the first time, the idea of “thinking alike” was rendered visible—not in poetry, but in biological data.

The Shape of a Positive Mind

There was more. The team discovered that optimists’ brains showed greater contrast between how they processed positive and negative future events. In other words, their minds drew a clear line between what was good and what was bad—reinforcing emotional clarity.

This challenges a common stereotype about optimists—that they merely sugarcoat the world, twisting bad news into palatable tales. The study suggests otherwise.

Optimists don’t ignore dark futures. They see them. But they view them from a distance, abstracting the pain and containing the fear. Where a pessimist may emotionally enter the scene of disaster, the optimist takes a step back, watching it unfold with the safety of mental distance.

That psychological space could be what shields them—not from reality, but from despair.

Where Brains Meet, Connection Begins

These findings may also explain something far deeper than personal happiness: why optimists tend to bond more easily with others.

If brains respond in similar ways to imagined futures, communication becomes smoother. Misunderstandings are fewer. Emotional reactions are predictable and shared. When someone says, “I think it’ll all work out,” and you truly believe that too—not just as a thought, but in your neural wiring—then that conversation doesn’t just feel good. It feels natural.

For pessimists, the picture is different. With each person visualizing a unique and often darker version of the future, shared understanding becomes harder to reach. Two people might use the same words—“I’m worried about tomorrow”—but mean completely different things inside their heads. That lack of alignment can breed disconnection, even loneliness.

It’s not just a matter of mood. It’s a matter of neurological resonance.

Nature, Nurture, and the Future Self

Kuniaki’s study doesn’t stop at discovery. It ends with a question that strikes at the heart of who we are.

Is this brain-alignment among optimists something they’re born with? A genetic melody passed down like eye color or height? Or is it a tune they learn over time, shaped by experience, dialogue, and the emotional music of relationships?

The answer isn’t yet clear. But the implications ripple outward.

If shared optimism helps people bond more easily, and if that optimism can be taught or nurtured, then perhaps we can design a world that fosters deeper empathy and stronger community. Schools, families, even public messaging could become not just vessels of information, but engines of emotional alignment.

And on a more personal level, if you’ve ever felt disconnected—if your thoughts about tomorrow seem darker or lonelier than those around you—this research offers both an explanation and a path forward. You may not be “wired wrong.” You may simply be imagining a different future. And perhaps, with time and the right kind of connection, even that future can change.

A New Language of the Mind

In a world increasingly divided—by politics, by ideology, by belief—it’s easy to think that understanding others is a lost art. But Kuniaki’s research shows something radically hopeful.

Understanding might not start with words at all. It might begin inside the mind, in the electric patterns we don’t even realize we share. Optimists, bound by common visions, remind us that shared futures make for shared realities. Pessimists, each with their unique maps, show the complexity and richness of the human experience.

Both offer something essential. And both deserve to be understood.

But now, thanks to a team that dared to peer into the hidden folds of thought, we no longer have to guess what it means to be on the same wavelength. We can see it. We can measure it. And maybe—just maybe—we can create more of it.

Reference: Yanagisawa, Kuniaki, Optimistic people are all alike: Shared neural representations supporting episodic future thinking among optimistic individuals, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2511101122. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2511101122