Around the world, women on average live longer than men. This pattern is not bound by borders, cultures, or even centuries—it stretches across nearly all human populations and historical periods. Whether in modern industrial nations with advanced healthcare or in earlier centuries marked by higher mortality, women tend to outlive men. The gap is not always wide, and in some countries it has narrowed thanks to improved medicine, nutrition, and safer living conditions. Yet, intriguingly, new research suggests that this difference may never fully disappear. The roots of the disparity run deeper than culture or lifestyle; they are woven into biology and shaped by millions of years of evolution.

A recent study by an international team led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, published in Science Advances, has shed new light on this mystery. By examining lifespan differences across more than a thousand bird and mammal species, the researchers uncovered insights into one of biology’s long-standing puzzles: why males and females age differently.

Longevity Written in Chromosomes

One of the most compelling explanations for the sex gap in lifespan lies in genetics—specifically, sex chromosomes. In mammals, females possess two X chromosomes, while males have one X and one Y. This difference may give females a protective edge. If one X chromosome carries a harmful mutation, the second X can often compensate, reducing the likelihood of disease or developmental problems. Males, by contrast, have no such backup. With only a single X, any harmful mutations can be more detrimental, potentially reducing lifespan.

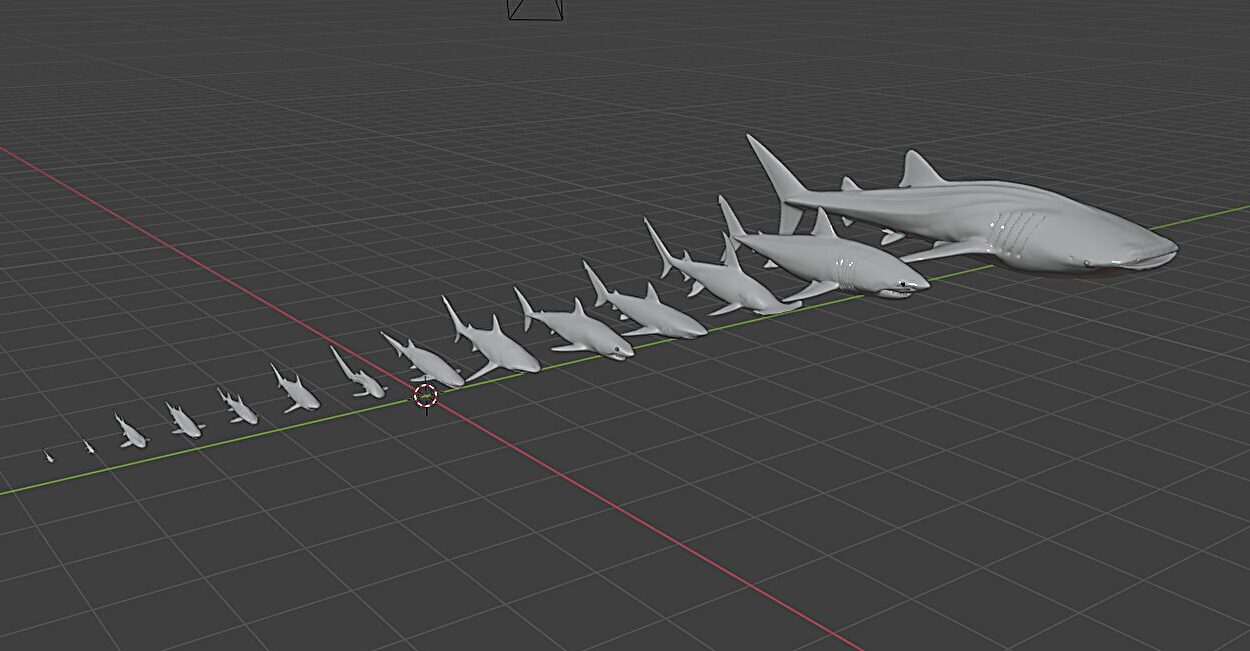

This concept is known as the “heterogametic sex hypothesis.” In mammals, the heterogametic sex is male (XY), which helps explain why females often outlive males. But in birds, the system is flipped: females are the heterogametic sex, with ZW chromosomes, while males are homogametic (ZZ). Consistent with this hypothesis, the study found that in most mammal species (about 72 percent), females lived longer—by an average of twelve percent. Yet in most bird species (about 68 percent), males lived longer, with an average advantage of five percent.

This finding suggests that sex chromosomes are indeed a powerful factor in shaping lifespan differences. Yet they are not the entire story. Exceptions abound. In many birds of prey, for instance, females are both larger and longer-lived than males. Clearly, other forces are at play.

The Price of Competition: Sexual Selection

Life is not only about survival—it is also about reproduction. And here, the strategies of males and females diverge in ways that profoundly shape how long they live. Sexual selection, the evolutionary pressure to attract mates and compete for reproduction, often drives males to develop traits that are both spectacular and costly. Bright plumage, antlers, tusks, large body size, and aggressive behaviors may all improve mating success, but they come at a price: higher energy demands, greater risk of injury, and sometimes greater visibility to predators.

In many polygamous mammal species—where males compete intensely for access to multiple females—this competitive pressure is particularly strong. Male lions, for instance, grow large, fight fiercely, and often die younger than lionesses. Among baboons and gorillas, too, males frequently outlive their reproductive usefulness and succumb to injuries or the cumulative costs of competition earlier than females. The new study supports this pattern: in polygamous species with strong male competition, lifespan gaps were more pronounced, with males dying younger.

Birds, by contrast, are often monogamous. In many species, males and females share parental duties and face similar survival pressures. The result is a narrower lifespan gap—and in many cases, a male advantage. Sexual selection, therefore, is a key force that sculpts lifespan differences across species.

The Investment of Parenthood

Another factor influencing longevity is parental care. Raising offspring requires time, energy, and often sacrifice, and the sex that invests more heavily in child-rearing may also live longer. Among mammals, females typically bear the greater burden—pregnancy, nursing, and, in many species, the majority of caregiving. Evolutionary theory suggests that natural selection favors longer female lifespans in these cases, ensuring that mothers survive long enough for their offspring to reach independence.

In long-lived species such as primates, this maternal advantage is especially pronounced. Human females, for instance, often live long past their reproductive years, a phenomenon sometimes linked to the “grandmother hypothesis”: older women increase the survival chances of their grandchildren, indirectly supporting the survival of their genes. This evolutionary benefit may help explain why human women often enjoy such extended lifespans compared to men.

In birds, the equation can look different. Many species share parental duties, and in some, males even invest more in offspring care than females. This greater male investment is consistent with the finding that in many bird species, males outlive females.

Zoo Life and the Persistence of the Gap

If environmental dangers drive the lifespan gap—such as predators, disease, or harsh climates—then removing those pressures should equalize male and female lifespans. To test this, the researchers turned to zoo populations, where animals live under controlled, protected conditions.

The results were striking. Even in zoos, sex differences in lifespan persisted. The gaps were sometimes smaller than in the wild, but rarely disappeared altogether. This mirrors the human experience. Medical advances, better nutrition, and improved sanitation have narrowed the gap between men and women, yet women still live longer almost everywhere. The persistence of these differences suggests they are not merely accidents of culture or environment, but products of deep evolutionary history.

The Evolutionary Roots of Aging

The study highlights a profound truth: lifespan differences between the sexes are not random quirks. They are shaped by fundamental evolutionary processes—genetics, sexual selection, parental care, and reproductive strategies. These forces interact in complex ways, producing patterns that echo across species and persist even when environmental conditions change.

For humans, the message is sobering yet fascinating. While lifestyle, healthcare, and culture all matter greatly, biology has set the stage. Men and women do not simply age differently because of social factors; they age differently because of evolutionary history stretching back hundreds of millions of years.

What It Means for Us Today

Understanding why women outlive men is not merely an academic exercise. It has practical implications for health, medicine, and social planning. As populations age, the fact that women typically spend more years in later life has profound effects on caregiving, pensions, and healthcare systems. Moreover, studying sex differences in aging may help scientists unlock new treatments for age-related diseases, benefiting both sexes.

On a personal level, it challenges us to see longevity not only as a matter of individual choice—diet, exercise, lifestyle—but also as part of a grand evolutionary narrative. Each lifespan carries echoes of ancestral struggles, mating strategies, and genetic inheritances that reach far beyond a single human life.

A Future Written in the Past

Will the gap between women and men ever close? The evidence suggests it is unlikely. While medicine may continue to improve survival for both sexes, the underlying biological and evolutionary forces remain. The longer female lifespan, deeply rooted in chromosomes, sexual selection, and parental care, is a pattern etched into the fabric of life itself.

Yet rather than seeing this as a limitation, we might see it as a reminder of our shared history with the rest of the animal kingdom. The differences in how we age connect us to gorillas and baboons, to lions and birds, to countless species shaped by the same forces. In these differences lies a story of survival, adaptation, and the many ways life has evolved to balance the competing demands of reproduction and longevity.

In the end, the fact that women live longer than men is not simply a statistic. It is an evolutionary tale, one that reveals how deeply biology and history are entwined. To understand it is to glimpse the threads that tie us not only to each other, but to all of life on Earth.

More information: Sexual selection drives sex difference in adult life expectancy across mammals and birds, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ady8433