The Moon has always hovered at the edge of human imagination. Long before rockets or telescopes, it was a silent companion in the night sky, marking time, shaping tides, and inspiring myths across civilizations. Yet in the twentieth century, humanity did something unprecedented: it turned that distant symbol into a physical destination. For a brief and astonishing moment, human footprints marked the lunar surface. Then, almost as suddenly as we arrived, we stopped going. For decades, the Moon remained untouched by human hands, visited only by robotic explorers and distant cameras.

This pause has often been misunderstood as a technological failure or a loss of interest, but the reality is far more complex. The story of why we stopped going to the Moon is inseparable from politics, economics, scientific priorities, and human psychology. Equally important is the story of why we are returning now, in a world profoundly different from the one that launched Apollo. The renewed push toward the Moon is not a nostalgic replay of past glory but a carefully recalibrated effort shaped by new science, new technologies, and new ambitions.

To understand this journey, we must look closely at what made the first lunar landings possible, what caused them to end, and why the Moon once again stands at the center of humanity’s plans beyond Earth.

The Apollo Era and the First Lunar Triumph

The Apollo missions emerged from a unique historical moment defined by intense geopolitical rivalry. During the Cold War, space became a symbolic battlefield where technological prowess and ideological superiority were publicly displayed. When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik in 1957 and later sent the first human, Yuri Gagarin, into orbit, the United States perceived a profound challenge to its global standing. Spaceflight was no longer a scientific curiosity; it was a measure of national power.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy announced the ambitious goal of landing a human on the Moon and returning them safely to Earth before the decade’s end. This declaration was not based on immediate scientific necessity, but on strategic urgency. At the time, the technology to achieve such a feat barely existed. Rockets were unreliable, computers were primitive by modern standards, and human spaceflight itself was still experimental. Yet the political will was immense, and funding followed accordingly.

The Apollo program mobilized hundreds of thousands of scientists, engineers, and technicians. It accelerated advances in rocketry, materials science, navigation, and computing. Most importantly, it accepted extraordinary risks. Astronauts flew on vehicles that were powerful but unforgiving, where failure often meant death. The tragic Apollo 1 fire underscored these dangers, yet the program continued, driven by a sense that the mission transcended individual lives.

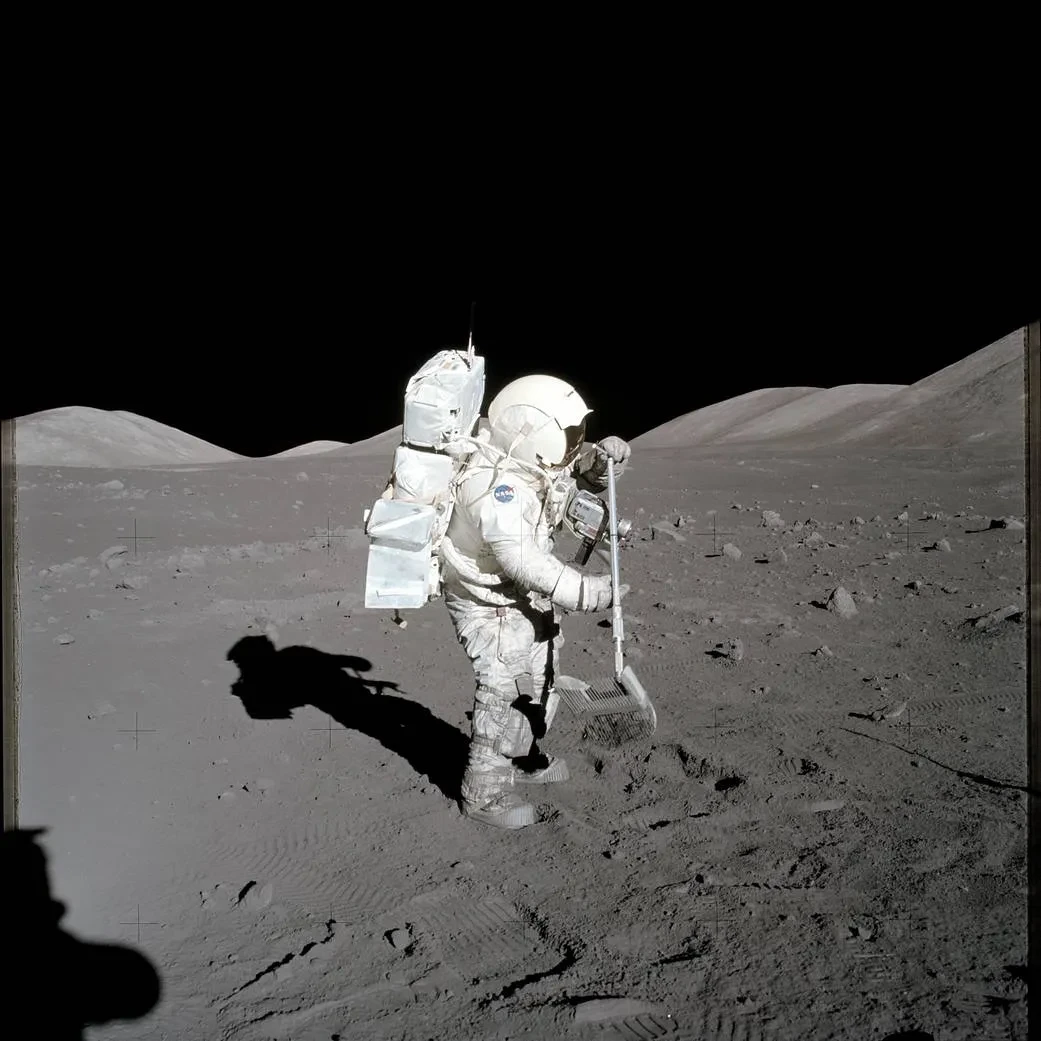

Between 1969 and 1972, six Apollo missions successfully landed humans on the Moon. Astronauts conducted experiments, collected lunar samples, and demonstrated that humans could work on another world. These missions transformed the Moon from a distant object into a tangible place, a landscape with dust, rocks, and horizons shaped by ancient impacts. Scientifically, Apollo revolutionized planetary science, providing insights into the Moon’s formation and the early history of the solar system.

Yet even at the moment of triumph, the seeds of Apollo’s end were already present.

The Changing Political Landscape After Apollo

The Apollo program was extraordinarily expensive. At its peak, it consumed a significant fraction of the United States federal budget. This level of investment was politically sustainable only under the intense pressure of Cold War competition. Once the primary objective was achieved and the symbolic victory secured, the political justification for continued lunar missions weakened rapidly.

By the early 1970s, public attention shifted. The Vietnam War, economic challenges, and social upheaval demanded resources and focus. The Moon, once a stage for global spectacle, began to feel distant from the immediate concerns of everyday life. To many policymakers, repeated lunar landings appeared redundant. Each mission was scientifically valuable, but none carried the dramatic impact of the first.

At the same time, the Soviet Union never attempted a crewed lunar landing, largely abandoning its own lunar ambitions after technical setbacks. Without a clear competitor, the urgency that had propelled Apollo evaporated. Space exploration remained important, but it was no longer framed as a race that demanded extreme spending and risk.

As budgets tightened, Apollo missions were canceled. Plans for extended lunar bases and more ambitious exploration were shelved. The final Apollo mission, Apollo 17, lifted off in December 1972. When its astronauts departed the Moon, no one knew that it would be the last human visit for more than half a century.

Scientific Priorities and the Shift Toward Earth Orbit

Another crucial factor in the end of lunar missions was a shift in scientific and strategic priorities. While Apollo provided invaluable lunar data, many scientists argued that comparable or greater scientific returns could be achieved through robotic missions at far lower cost. Uncrewed spacecraft could explore planets, moons, and asteroids without risking human lives or requiring massive life-support systems.

At the same time, attention turned toward near-Earth space. Satellites were becoming essential for communication, weather forecasting, navigation, and national security. Human activity in low Earth orbit promised practical benefits that the Moon could not immediately offer. Space stations, in particular, were seen as laboratories for long-duration human spaceflight, microgravity research, and international cooperation.

The development of the Space Shuttle embodied this new direction. Designed to be reusable, it aimed to reduce the cost of access to space and support a wide range of missions in Earth orbit. Although the Shuttle ultimately fell short of its cost-saving promises, it became the centerpiece of human spaceflight for decades. The Moon, by contrast, receded into the background.

This strategic realignment did not reflect a belief that the Moon lacked importance, but rather a calculation about where limited resources could be most effectively deployed. Physics and engineering realities meant that sustained lunar exploration would require infrastructure and investment comparable to Apollo, without the same political motivation to justify it.

The Psychological Dimension of Lunar Exploration

Beyond budgets and politics, there was also a psychological dimension to humanity’s retreat from the Moon. The first landing was a singular moment, watched by millions and etched into collective memory. Subsequent missions, though scientifically richer, struggled to capture the same sense of wonder. Familiarity dulled novelty, and the extraordinary became routine.

This phenomenon reflects a broader truth about human attention. Exploration thrives on the unknown, and once the Moon had been visited repeatedly, it no longer felt like the ultimate frontier. Mars, the outer planets, and the vastness beyond the solar system beckoned more strongly to scientific imagination, even if they were not yet accessible to humans.

Moreover, the Apollo missions revealed that living and working on the Moon was exceptionally difficult. Lunar dust was abrasive and pervasive. The environment was harsh, with extreme temperature swings and constant exposure to radiation. The romantic image of lunar exploration gave way to a more sober understanding of its challenges. Without a compelling long-term purpose, enthusiasm waned.

The Moon in the Age of Robotic Exploration

While humans stayed away, the Moon was far from abandoned. Robotic missions continued to expand our understanding of its geology, composition, and history. Orbiters mapped the surface in exquisite detail, while landers and rovers conducted localized studies. These missions revealed that the Moon is far more complex than once believed.

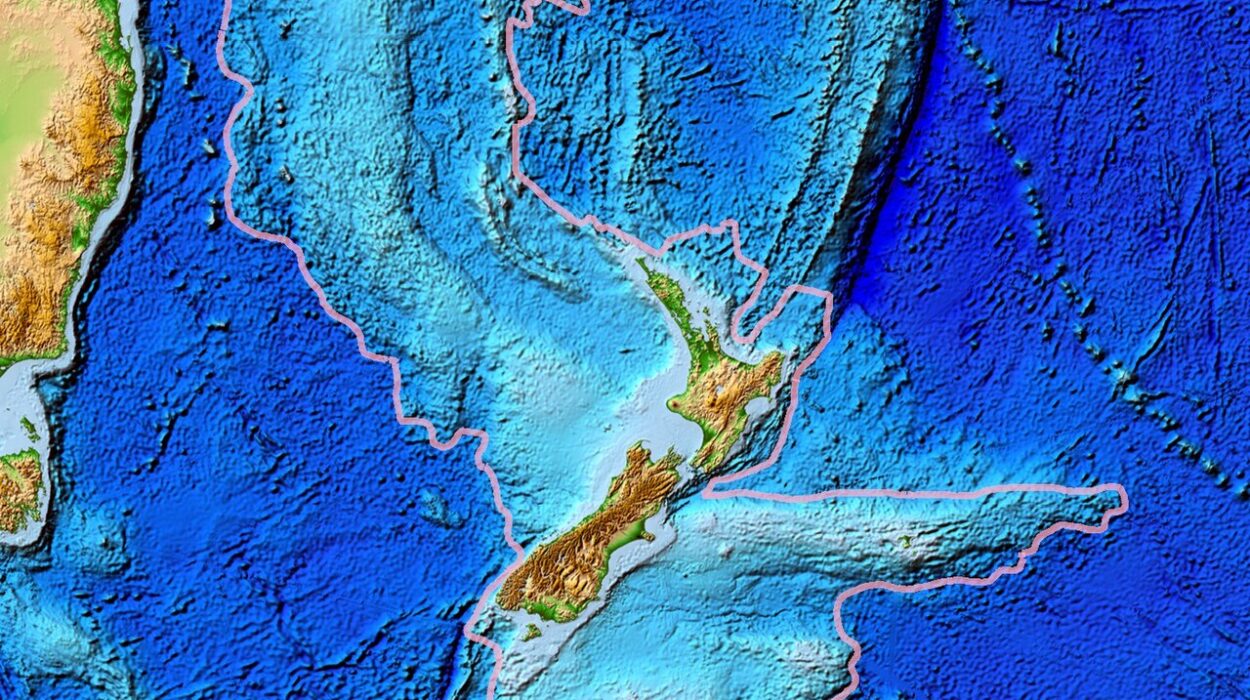

One of the most significant discoveries was the presence of water ice in permanently shadowed regions near the lunar poles. Shielded from sunlight, these areas can preserve volatile compounds for billions of years. This finding transformed scientific and strategic thinking about the Moon. Water is not only scientifically interesting but also practically valuable, as it can be used to support human life and even produce rocket fuel.

Robotic missions also provided insights into lunar resources, impact processes, and the Moon’s internal structure. These discoveries gradually reshaped the Moon’s image from a barren relic of exploration history into a potential stepping stone for deeper space missions.

Why the Moon Matters Again

The renewed interest in returning to the Moon arises from a convergence of scientific, technological, and strategic factors. Unlike the Apollo era, today’s lunar ambitions are not driven by a single geopolitical rivalry but by a broader vision of sustainable exploration and international collaboration.

Scientifically, the Moon offers unique opportunities. Its surface preserves a record of the early solar system that has been erased on Earth by tectonics and erosion. Studying ancient lunar rocks can provide insights into planetary formation and the conditions that shaped Earth itself. The Moon also serves as an ideal platform for astronomy, particularly radio astronomy, shielded from Earth’s electromagnetic noise.

From an engineering perspective, the Moon is an accessible testing ground for technologies needed for Mars and beyond. Its proximity allows relatively rapid communication and rescue options compared to more distant destinations. Developing habitats, life-support systems, and surface operations on the Moon provides invaluable experience for future interplanetary missions.

Strategically, the Moon is increasingly viewed as part of humanity’s expanding sphere of activity in space. As more nations and private companies develop space capabilities, the Moon becomes a focal point for cooperation, competition, and governance. Establishing a sustained human presence there is seen as a way to shape norms and practices for future space exploration.

New Technologies and a Different Approach

One of the most profound differences between the Apollo era and today is technological evolution. Advances in computing, materials science, robotics, and propulsion have transformed what is possible. Modern spacecraft are more autonomous, more efficient, and more reliable than their predecessors. Digital systems that once filled rooms now fit on microchips, enabling precise navigation and control.

Equally significant is the rise of commercial spaceflight. Private companies have introduced new models for developing and launching spacecraft, often at lower costs and with greater flexibility. This shift reduces the financial burden on governments and encourages innovation through competition.

Today’s approach to lunar exploration emphasizes sustainability rather than short-term spectacle. Instead of isolated missions, the goal is to establish an enduring presence. This includes the development of lunar orbiting platforms, surface habitats, and supply chains that rely on local resources. The Moon is no longer just a destination; it is becoming an environment to inhabit.

International Collaboration and a Shared Moon

Unlike the Cold War-driven Apollo program, modern lunar efforts involve extensive international cooperation. Space agencies from multiple countries contribute expertise, technology, and funding. This collaborative model reflects a recognition that the challenges of space exploration are too great for any single nation to address alone.

Such cooperation also carries symbolic weight. The Moon, visible to all of humanity, represents a shared heritage rather than a national trophy. Collaborative exploration fosters scientific exchange and reduces the risk of conflict over resources and territory. It also aligns with broader efforts to establish norms for peaceful activity in space.

At the same time, collaboration does not eliminate competition. Nations seek to demonstrate leadership and technological capability, and strategic considerations remain influential. The difference lies in how these ambitions are balanced with shared goals and mutual benefit.

Preparing for Life Beyond Earth

Returning to the Moon is not an end in itself, but part of a larger vision for humanity’s future in space. Long-term survival beyond Earth requires learning how to live sustainably on other worlds. The Moon provides a relatively accessible environment in which to develop and refine these capabilities.

Life on the Moon demands solutions to fundamental problems: protecting humans from radiation, providing reliable power, recycling air and water, and maintaining psychological well-being in isolation. Addressing these challenges advances knowledge that is directly applicable to future missions to Mars and other destinations.

The Moon also offers opportunities to test in-situ resource utilization, the practice of using local materials rather than transporting everything from Earth. This approach is essential for reducing costs and enabling long-duration missions. Learning how to extract and use lunar resources marks a crucial step toward a permanent human presence in space.

The Emotional Meaning of Return

Beyond science and strategy, the return to the Moon carries deep emotional significance. For generations, the Apollo landings symbolized the heights of human achievement and cooperation. Their abrupt end left a sense of unfinished business, a question lingering in cultural memory: why did we stop?

Returning to the Moon is an opportunity to reconnect with that spirit of exploration while redefining it for a new era. It is a chance to inspire curiosity and ambition in a world facing complex challenges on Earth. Space exploration does not solve those challenges directly, but it offers perspective, reminding us of our shared vulnerability and potential.

The Moon’s silent landscape has waited unchanged while humanity evolved. To return is to acknowledge both continuity and change, to step again onto a familiar yet profoundly alien world with new eyes and new intentions.

A Different Kind of Journey Forward

The question of why we stopped going to the Moon reveals that exploration is never just about technology. It is shaped by values, priorities, and collective imagination. Apollo succeeded because it aligned political will, public support, and scientific ambition in a rare and powerful convergence. When that alignment dissolved, the journey paused.

Today, the reasons for returning are more complex and, in many ways, more durable. They rest on scientific discovery, sustainable exploration, and a long-term vision of humanity’s place in the cosmos. The Moon is no longer a destination to conquer but a partner in learning how to live beyond Earth.

As humanity prepares to return, the Moon stands as both a reminder of past triumphs and a gateway to future possibilities. The silence that followed Apollo was not an ending, but an interlude. Now, with deeper understanding and renewed purpose, the journey resumes, not as a race to plant flags, but as a careful and hopeful step toward a shared future among the stars.