Skin is more than a protective barrier. It is the most visible part of who we are, carrying our identity, our culture, and our first impressions. For people with vitiligo — a chronic autoimmune disease that causes patches of skin to lose their natural pigment — that visibility can become a source of deep emotional struggle.

A new study led by the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA reveals that living with vitiligo is not only a dermatological challenge but also a significant mental health concern. The research, recently accepted by JAAD International, shows that people with vitiligo face an elevated risk of depression, with Black and Hispanic patients disproportionately affected.

Vitiligo: More Than Skin Deep

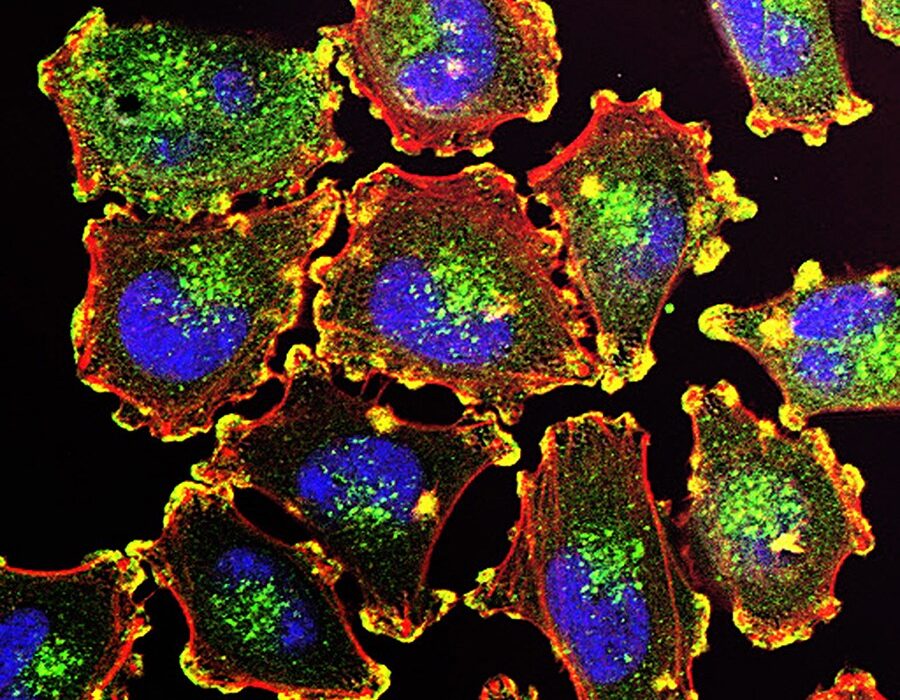

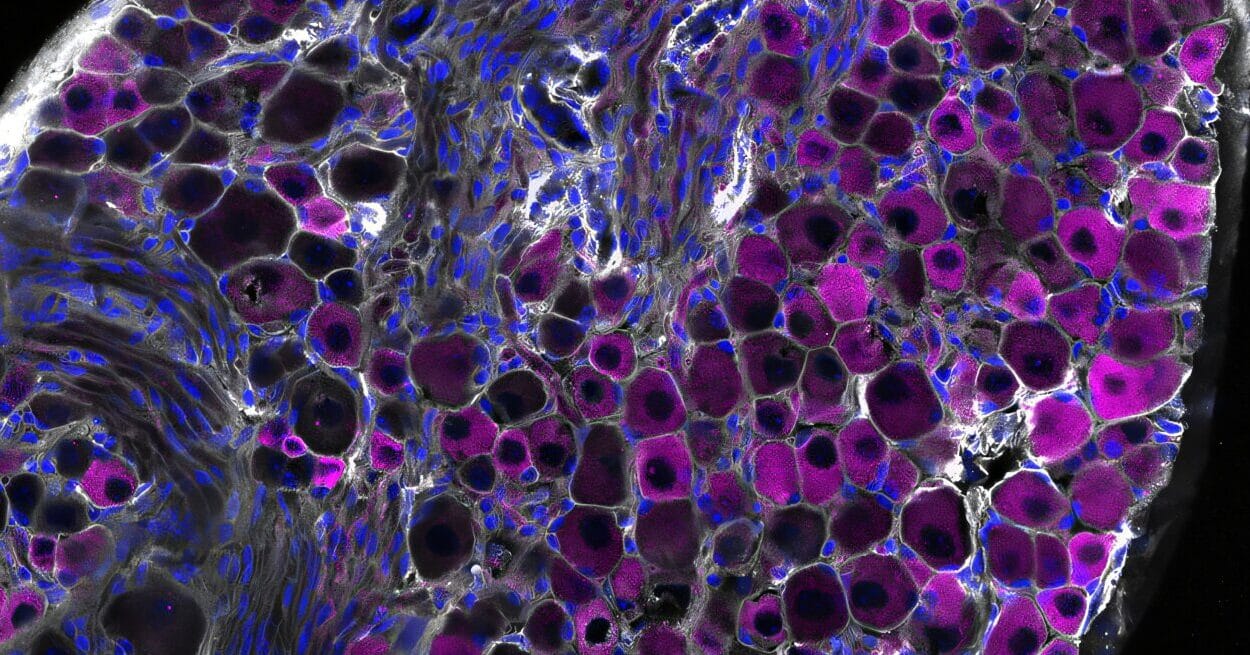

Vitiligo affects roughly 1% of the global population, yet its impact is often misunderstood. The condition occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the skin. The result is a patchwork of lighter areas that can appear anywhere on the body.

While vitiligo does not cause physical pain, its psychological toll can be profound. Patients often report lowered self-esteem, social isolation, and encounters with stigma or discrimination. For many, the mirror becomes a reminder not of identity, but of difference.

“Skin disorders like vitiligo are visible in a way that most chronic illnesses aren’t,” explained the UCLA-led research team. “That visibility changes how patients are treated by others — and how they see themselves.”

Mining the Data for Answers

To better understand the relationship between vitiligo and mental health, researchers turned to the NIH All of Us Program, one of the largest health databases in the United States. They examined data from more than 254,000 individuals collected between 2018 and 2024.

From this pool, 1,087 patients with vitiligo were matched to 5,435 control patients without vitiligo, carefully balanced by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, education, and insurance. This approach allowed researchers to isolate the effects of vitiligo itself, reducing the noise of other factors that might influence depression risk.

Their findings were clear: patients with vitiligo had a 34% higher overall risk of depression compared to people without the condition. But when the team looked closer at the data by race and ethnicity, striking disparities emerged.

Unequal Burdens, Unequal Risks

For Black patients, the numbers were stark. Those with vitiligo were more than twice as likely to experience depression as Black patients without vitiligo. Hispanic patients also faced significantly higher odds — about 45% greater risk compared to Hispanic controls.

Meanwhile, the data told a different story for other groups. White patients with vitiligo did not show a significant increase in depression risk. Asian patients even showed a non-significant lower risk, though the smaller sample size means those findings should be interpreted with caution.

These differences, the researchers suggest, may reflect a mix of cultural, social, and systemic factors. Vitiligo patches may be more visibly pronounced on darker skin, potentially amplifying stigma and unwanted attention. Cultural attitudes toward skin differences, along with varying levels of access to mental health and dermatologic care, may also play powerful roles.

Beyond the Numbers: A Human Story

For patients, these statistics are not just data points. They mirror lived realities. Imagine a teenager with vitiligo, dreading the stares at school, or an adult avoiding social gatherings for fear of judgment. In some communities, vitiligo carries cultural misconceptions that can compound isolation.

“These are not just medical challenges,” the study’s authors emphasized. “They are deeply human ones. Depression can shadow every aspect of life, from relationships to work to basic well-being.”

Toward Better, Fairer Care

The study highlights an urgent need for integrated care models that address both the physical and psychological dimensions of vitiligo. The researchers propose future studies on how factors like the location of vitiligo patches, age at onset, and treatments such as phototherapy or ruxolitinib cream influence depression risk.

Most importantly, they call for collaborative approaches between dermatology and psychiatry, ensuring that patients are supported not only in managing their skin but also their mental health.

“Our findings reinforce that vitiligo is not just a cosmetic issue,” the team wrote. “It is a condition that demands holistic care, with particular attention to the communities bearing the heaviest burdens.”

A Path Toward Understanding

Vitiligo may not shorten life expectancy, but it can profoundly shape life experience. By shining light on the hidden mental health toll — and on the uneven ways that toll is distributed — this study opens the door for more compassionate, tailored care.

As researchers continue to untangle the connections between skin, identity, and mental well-being, one truth grows clearer: healing must reach more than the surface.

More information: Matthew J. Yan et al, Variation in Depression Risk by Race and Ethnicity in Vitiligo, JAAD International (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jdin.2025.07.005