Humans rarely think about the quiet choreography of their own breathing. Yet every inhale, every subtle shift in rhythm, is part of a larger conversation between body and world. Scientists have long known that animals actively gather information through movement—eyes darting, ears pivoting, hands reaching. But in the realm of smell, this dance is far more delicate. It takes the form of a sniff: a brief, purposeful pull of air meant to gather chemical clues from the environment. What remained mysterious was whether this tiny act of sampling could change depending on what, exactly, the nose encountered.

A team at Northwestern University set out to follow this trail. Their curiosity led them into the hidden dynamics of sniffing itself, asking whether each inhalation carries a signature shaped by the odor it is trying to understand. Their findings, published in Nature Human Behavior, reveal that human sniffs are not merely mechanical breaths but fine-tuned responses to the world—responses so distinct that they can quietly encode the identity of specific odors.

“Our work was motivated by a long-standing interest in human breathing and sniffing,” said Vivek Sagar, first author of the study. “We had previously observed that our human subjects smelled various odors in distinct ways. However, we were not sure to what extent information about each odor was present in the way odors were sniffed. Moreover, if this odor signature was reliably present in the sniffs, which brain areas were important for this effect?”

A Library of Odors and the Sniffs That Followed

To tackle a question hidden in the smallest of movements, the researchers needed an exceptionally rich dataset—something capable of capturing fleeting nuances across many different smells. They turned to a previously published resource known as the neural encoding models of olfaction, or NEMO, dataset. It contained more than 12,000 trials in which three participants, inside an MRI scanner, encountered 160 distinct odors.

The MRI setting, with its magnetic fields and radio waves, served as both an observer of the brain and a controlled environment for scent delivery. Every sniff was recorded, allowing researchers to map the precise dynamics of each inhalation as the odors unfolded.

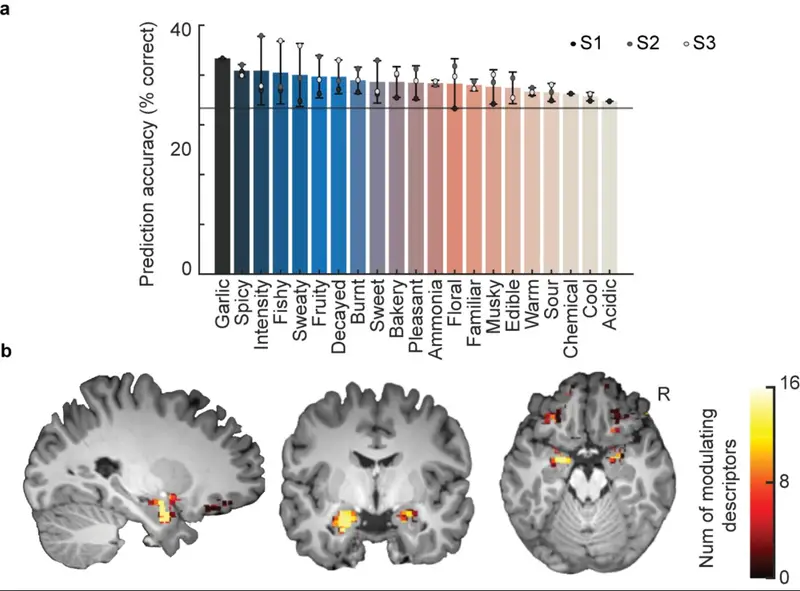

“We needed this rich dataset, since the effect size of odor-induced sniff modulation could be small,” Sagar explained. Their challenge was to trace the subtle fingerprints left on sniffing behavior by the odors themselves. To do this, the team used a wide array of computational approaches, including machine learning. Algorithms were trained to guess which odor a participant was smelling by reading only their sniffing patterns.

The results were striking: the algorithms succeeded. Human sniffing, it turned out, was far more expressive than scientists had realized. Each odor left its own trace in the form of specific timing, depth, or other features of inhalation—features that a computer could interpret even when humans might not consciously notice them.

Following the Signals into the Brain

Patterns in behavior are only half the story. The team sought to understand where in the brain this subtle modulation might originate. Because the participants were inside an MRI scanner for every trial, the study offered a rare opportunity to directly link sniffing behavior to neural activity.

By focusing on regions known to play central roles in olfaction, particularly the amygdala, the researchers began to see how sensory sampling and brain dynamics formed a loop of continuous feedback. Odor information did not simply travel passively into the system; it shaped the very act of sampling itself.

“We performed a repertoire of analyses to link sniffing dynamics to odor properties, but crucially, we could use a machine learning algorithm to predict which odor the subjects were sniffing based on their sniffing dynamics,” Sagar said. “Further, we could find the neural basis of this effect in the olfactory regions, such as the amygdala, by focusing our analysis on the MRI data.”

This neural connection echoed earlier observations from medical research. “Further, identifying brain regions such as the amygdala that are involved in this process is in line with previous work in epilepsy literature that has identified involvement of the amygdala in apnea and disruptions in breathing,” Sagar added. In other words, the amygdala has long been associated with patterns of breathing, and its participation in odor-guided sniffing now provides a deeper link between scent, perception, and physical response.

Where Smell and Behavior Meet

What emerged from the study was a new understanding of olfaction as an active loop, not a passive channel. Sniffing does not merely deliver odor molecules to receptors. It adjusts, moment by moment, in response to the very stimuli it seeks to perceive. Even perceptual qualities of odors appear to be mirrored in tiny variations in sniffing patterns.

“We demonstrated that odor information can reliably influence sniffing dynamics, suggesting that olfaction is a closed-loop phenomenon with active sensing similar to other sensory systems, such as vision and audition, where stimulus characteristics influence the sampling behavior,” said Sagar.

This means the human nose may work more like the human eye than previously appreciated. Just as eyes flicker between points of interest and adjust to changing light, the nose may also refine its approach, inhaling differently depending on the meaning or structure of the stimulus.

A Future Shaped by a Simple Breath

For Sagar and his colleagues, this discovery opens up entirely new lines of inquiry. If sniffing changes depending on what we perceive, could deliberate changes in sniffing alter what we perceive? Could the act of inhaling in different ways reshape the experience of a scent?

“A natural next step would be to further flesh out this link between sniffing and odor perception and test whether sniffing the same odor in different ways could alter odor perception in predictable ways,” Sagar said. “We are also interested in examining odor or breathing in different cognitive, affective, and spatial contexts.”

This curiosity highlights a broader shift in the field: the recognition that olfaction is not an isolated sense but part of a dynamic interplay between mind, body, and environment.

Why This Research Matters

Understanding how sniffing reflects odor identity does more than illuminate a hidden aspect of human behavior. It redefines how scientists think about sensory perception as a whole. If smell is part of an active feedback loop—one in which the brain and body continuously shape each other’s responses—then decoding this loop could enrich research on emotion, memory, health, and human–environment interactions.

By revealing that each sniff carries information about what we are sensing, the study invites a reexamination of the everyday act of breathing. In these small, rhythmic movements, the body is not simply taking in air. It is engaging in a constant dialogue with the world, adjusting itself to understand more clearly. Through this quiet and continuous conversation, the human sense of smell emerges not as a passive detector but as an active participant in perception itself.

More information: Vivek Sagar et al, The human brain modulates sniffs according to fine-grained perceptual features of odours. Nature Human Behaviour(2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02327-x