In the grand tapestry of human history, illness has often been the invisible thread weaving through families, communities, and civilizations. Among the countless diseases that afflict humankind, some remain enigmas cloaked in complexity and misunderstood by much of the world. Sickle Cell Disease is one of these—both ancient and modern, specific and global, subtle and profound. It is a condition born of a single mutation, yet its ripples are felt across continents, races, and generations.

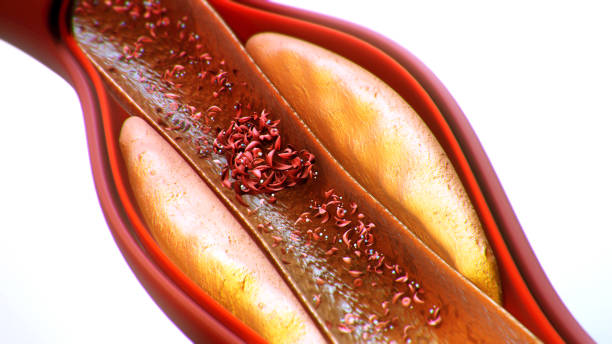

At the heart of Sickle Cell Disease lies the red blood cell, a marvel of microscopic engineering. These tiny, flexible discs travel through our bloodstream, ferrying oxygen to the body’s most remote corners. They are built for smooth sailing, crafted to squeeze through the narrowest vessels with grace and efficiency. But in individuals with sickle cell disease, something goes wrong. A small genetic change causes these life-giving cells to twist into distorted crescents, rigid and misshapen, resembling a farmer’s sickle more than a lifeline.

This change may seem subtle, a mere glitch in a strand of DNA, but its consequences are anything but small. The distorted cells get stuck, clump together, block blood flow, and die prematurely. What follows is a cascade of pain, organ damage, and a heightened vulnerability to infection. Yet for many, especially in under-resourced regions, understanding the origin of their pain is still a luxury. The disease hides in plain sight, frequently misdiagnosed, tragically untreated, and woefully underestimated.

An Inherited Legacy

Sickle Cell Disease is not contagious. It doesn’t pass from person to person like a virus or a parasite. Instead, it is inherited, passed down through generations like a hidden flaw in the family blueprint. For someone to have the disease, they must inherit two copies of the sickle cell gene—one from each parent. If they inherit only one, they carry the trait but typically do not experience the full fury of the disease.

The origins of this mutation are not random. They are a startling example of evolution’s grim compromise. In regions where malaria was historically rampant—across much of Sub-Saharan Africa, parts of the Middle East, India, and Mediterranean countries—carrying one copy of the sickle cell gene actually offered a survival advantage. It provided a degree of protection against the malaria parasite, allowing carriers to better resist severe infections. Nature, in its brutal pragmatism, had engineered a trade-off: protection in exchange for the risk of suffering in future generations.

As humans migrated, traded, and were forced across continents through colonization and slavery, the gene traveled too. Today, sickle cell disease is found in populations around the globe, with particularly high prevalence among people of African, Caribbean, Middle Eastern, Indian, and Mediterranean descent. This global spread has made sickle cell a worldwide health concern, transcending national borders and ethnic boundaries.

The Pain That Cannot Be Seen

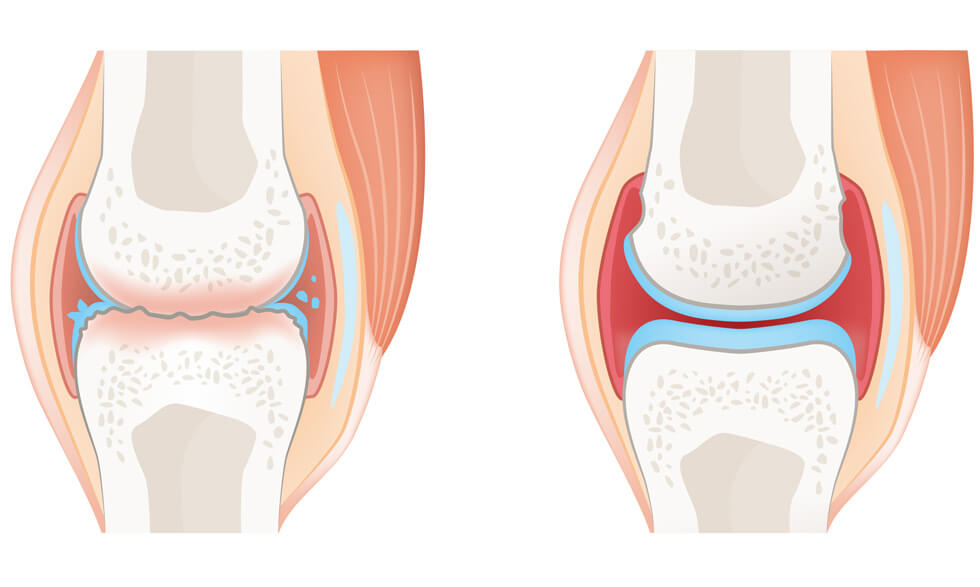

For those who live with sickle cell disease, the experience is often one of invisible agony. The hallmark of the condition is the sickle cell crisis—a sudden, unpredictable attack of intense pain caused by blocked blood vessels. These episodes can strike any part of the body: the chest, the abdomen, the joints, even the bones. The pain is not always responsive to medication and can last for hours, days, or even longer.

But the suffering doesn’t end with the crisis. Chronic complications accumulate over time. The constant destruction of red blood cells leads to anemia, leaving the patient tired and weak. The blocked vessels can damage organs, leading to strokes, kidney failure, lung problems, and heart disease. In children, it can cause delayed growth and impaired cognitive development. Infections lurk as constant threats due to weakened immunity. Eyes, hips, lungs—no organ is safe.

And then there is the psychological toll. Living with a chronic, painful, and stigmatized disease can wear down the spirit. Children miss school, adults miss work, and families miss out on a life not ruled by hospital visits and emergency rooms. The disease invades every aspect of life, silently sculpting the path a person can walk.

A Global Disease, An Unequal Battle

Though sickle cell disease affects people all over the world, the battle against it is far from equal. In high-income countries with access to comprehensive medical care, people with sickle cell can often live well into adulthood and lead relatively full lives. Early diagnosis through newborn screening, access to regular check-ups, preventive antibiotics, vaccines, pain management strategies, and advanced treatments like blood transfusions and hydroxyurea therapy have transformed what was once a death sentence into a manageable condition.

But in low- and middle-income countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, the picture is starkly different. In many of these regions, there is little to no access to screening, treatment, or even basic awareness. It’s estimated that the majority of children born with sickle cell disease in Africa die before their fifth birthday—an appalling statistic that reflects systemic health inequities rather than medical inevitability.

Sickle cell remains a neglected disease on the global stage. Despite affecting millions, it has historically received far less attention, funding, and research than other genetic disorders. The reasons are complex but rooted in socioeconomic disparity, racial inequity, and the geography of suffering. Where the disease hits hardest, the resources to fight back are often the most scarce.

The Science of Survival

The landscape of sickle cell treatment has evolved significantly in the last few decades. One of the most important breakthroughs has been hydroxyurea, a medication that helps reduce the number and severity of pain crises. It works by increasing the production of fetal hemoglobin, which helps prevent the sickling of red blood cells. Though not a cure, hydroxyurea has improved quality of life for thousands. It has been a lifeline, especially when paired with regular medical monitoring.

Blood transfusions are another cornerstone of treatment. They help dilute the sickled cells with healthy ones and reduce the risk of complications like stroke. For children at risk of strokes, regular transfusions have become a powerful preventive strategy.

Bone marrow and stem cell transplants offer the only potential cure for sickle cell disease. However, the procedure is complex, expensive, and risky. It requires a compatible donor—often a sibling—and can carry significant side effects, including the possibility of rejection or infection. While some children have been successfully cured, this remains out of reach for most, especially in resource-limited settings.

In recent years, new treatments have emerged from the growing field of genetic medicine. Therapies aimed at editing the faulty gene or reactivating dormant genes that produce healthier hemoglobin have shown promise. Clinical trials using CRISPR gene-editing technology have yielded encouraging results. For the first time, science is inching closer to a universal cure. But as always, the challenge lies in making these high-tech solutions accessible to the people who need them most.

Stigma, Silence, and Misunderstanding

Beyond biology, sickle cell disease is entangled in a web of cultural beliefs, misinformation, and stigma. In many parts of the world, it is shrouded in silence. Myths about its causes persist: some blame curses, bad spirits, or divine punishment. Others view it as a disease of shame, something to be hidden away rather than discussed or confronted.

This stigma often extends to family planning. In communities where carrier status is poorly understood, couples may be unaware of the genetic risks of passing the disease to their children. In other cases, individuals with the disease are discriminated against, facing barriers to education, employment, and marriage. Social isolation and internalized shame can deepen the emotional burden of living with the condition.

Education is a powerful antidote. When people understand how the disease is inherited and how it can be managed, they are empowered to make informed choices. Genetic counseling, community outreach, and public health campaigns are essential tools in breaking the silence. But these require investment, both in terms of money and political will—commodities that are not always available where they are most needed.

The Power of Advocacy and the Hope of Progress

One of the most inspiring aspects of the sickle cell story is the growing network of patient advocates, support groups, and medical professionals who are fighting back. Across Africa, Europe, the Americas, and beyond, grassroots movements have emerged to demand better care, increased funding, and global recognition.

Patients themselves have become some of the most powerful voices in the movement. Through social media, public speaking, and storytelling, they are raising awareness, sharing their journeys, and dismantling stereotypes. Organizations like the Sickle Cell Disease Association of America and the Sickle Cell Society in the UK have become key players in the global conversation, pushing for policy changes and driving research agendas.

There is progress. In 2021, the World Health Organization recognized sickle cell disease as a public health priority. Some countries have implemented newborn screening programs, created national treatment guidelines, or launched awareness campaigns. Pharmaceutical companies have invested in new therapies. And slowly, the scientific community has begun to prioritize sickle cell in the same way it has other genetic conditions.

Still, the road ahead is long. Until access to care is universal, until stigma is erased, until a cure is not a dream for the privileged but a reality for all—there is work to do.

A Disease, A Story, A Shared Responsibility

Sickle cell disease is more than a medical condition. It is a story of survival, a tale written in the blood and bones of millions. It speaks to the legacy of colonialism, the cost of inequality, the triumph of science, and the resilience of the human spirit. It challenges us to think not only as scientists or doctors, but as citizens of a shared world.

To truly understand sickle cell disease is to grasp its scientific intricacies and its social dimensions. It is to listen to the child in Lagos whose pain is dismissed as laziness. To the teenager in Atlanta who misses classes for transfusions. To the mother in Mumbai who walks miles to a clinic that has no medicine. Their stories are chapters in a global narrative we all have the power to shape.

We live in a time of extraordinary scientific capability. We have sequenced the human genome, edited DNA, and peered into the most distant corners of the universe. But our true greatness will not be measured by what we can do in the lab—it will be judged by how we choose to apply that knowledge. Will we let millions suffer because they are poor, black, or born in the wrong country? Or will we rise to the challenge of compassion?

Sickle cell disease can be understood. It can be treated. It can be cured. But it cannot be ignored.