In the intricate tapestry of human biology, some threads weave quietly, subtly fraying the body’s integrity long before anyone notices. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, or EDS, is one such thread—a mysterious condition that evades easy explanation, yet touches the lives of thousands around the world. Hidden behind hyperflexible joints, fragile skin, and chronic pain lies a spectrum of disorders that defy simple categorization. Often misunderstood or misdiagnosed, EDS remains a paradox: a disorder that is both rare and not rare, invisible and unmistakable, mild in some and life-altering in others.

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is not a single condition but a group of connective tissue disorders. Its name conjures images of historical intrigue, and indeed, its origins are rooted in the medical annals of two different nations. Edvard Ehlers, a Danish dermatologist, and Henri-Alexandre Danlos, a French physician, first described the syndrome in the early 20th century, identifying a peculiar pattern of symptoms in patients with highly elastic skin and unusually flexible joints. What they observed, however, was just the beginning of a far deeper biological mystery.

The Connective Tapestry: Understanding the Architecture of the Body

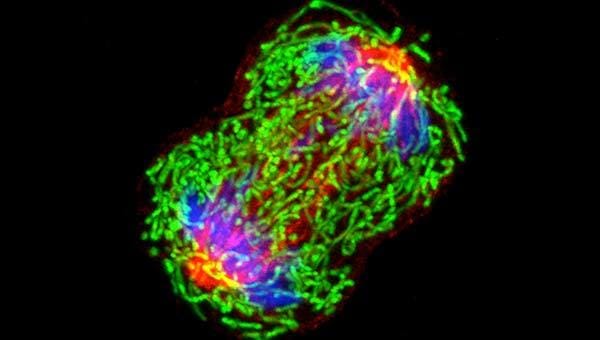

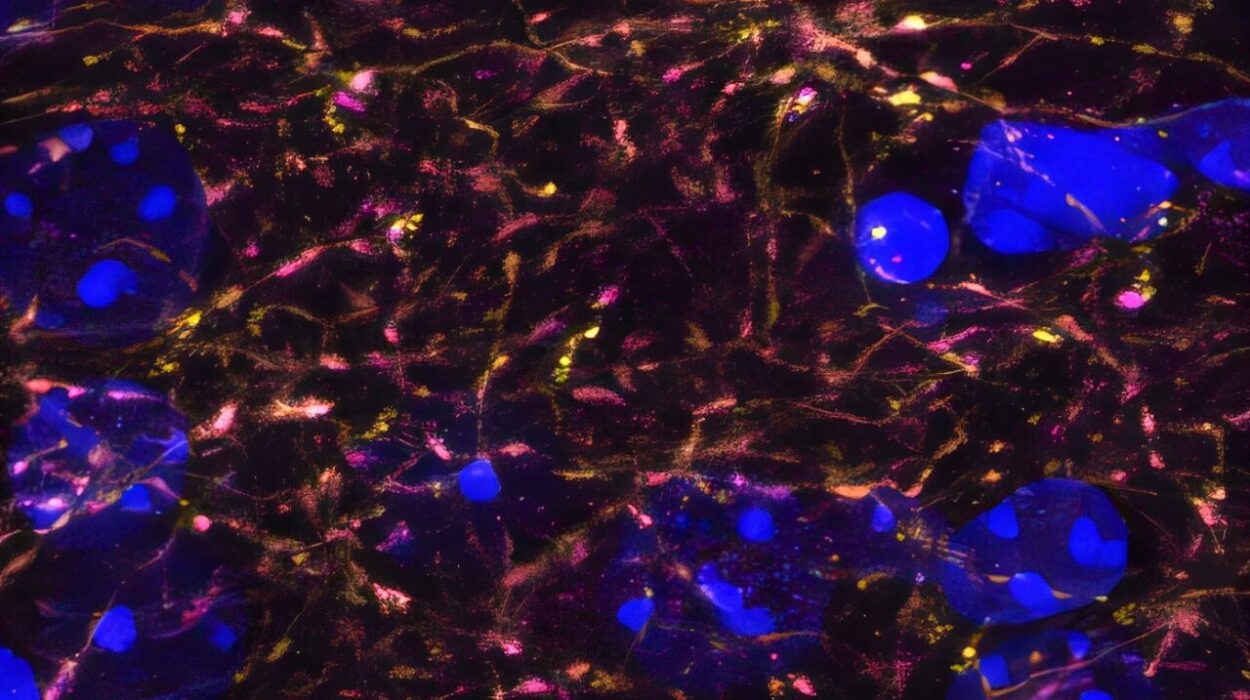

To truly understand EDS, one must first grasp the vital role of connective tissue. This tissue acts as the body’s internal scaffolding, providing structure and support for the skin, muscles, blood vessels, organs, and bones. Think of it as a complex meshwork, composed primarily of collagen, elastin, and other proteins that keep the body’s parts in place while allowing for movement and flexibility. Collagen, in particular, is a superstar in this system—responsible for strength and elasticity, it acts as the glue that binds the body together.

In individuals with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, however, this glue is defective. The collagen is either produced in insufficient quantities, constructed improperly, or broken down too quickly. As a result, the tissues it supports become weak and overly stretchy. This isn’t just a matter of bendy joints or soft skin; it’s a fundamental architectural flaw that can ripple throughout the entire body, manifesting in unpredictable and sometimes debilitating ways.

The Many Faces of EDS: A Spectrum of Subtypes

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is not a single diagnosis but a family of related disorders. Today, medical experts recognize thirteen subtypes of EDS, each with its own unique genetic cause, clinical features, and severity. The most common form is hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS), characterized by joint hypermobility, soft or velvety skin, and chronic pain. Unlike many of the other subtypes, hEDS currently has no identified genetic marker, making it particularly elusive in both diagnosis and understanding.

Classical EDS, on the other hand, is better understood and is linked to mutations in the COL5A1 or COL5A2 genes, which affect the structure of type V collagen. Individuals with classical EDS often have highly elastic, fragile skin that bruises easily and heals poorly, along with joint hypermobility.

Vascular EDS, one of the most severe forms, is caused by mutations in the COL3A1 gene, which affects type III collagen—a critical component of blood vessels and hollow organs. People with this subtype face the constant threat of arterial rupture, organ tearing, or life-threatening bleeding. For them, the syndrome is not just a matter of comfort or mobility but a matter of survival.

Despite their differences, all subtypes of EDS share a common thread: defects in connective tissue that disrupt the body’s natural balance and resilience.

The Struggle for Diagnosis: A Journey Through the Medical Maze

For many with EDS, the road to diagnosis is long, confusing, and frustrating. Symptoms often begin in childhood—frequent sprains, dislocations, bruises, or gastrointestinal complaints—but they are easily dismissed as growing pains or clumsiness. Because EDS affects multiple systems, patients often bounce between specialists: a rheumatologist for joint pain, a dermatologist for skin issues, a gastroenterologist for stomach troubles, and a cardiologist for heart palpitations.

Without a unified picture, the underlying syndrome can go unrecognized for years. For those with hypermobile EDS, the lack of a genetic test adds to the difficulty. Diagnosis depends on clinical criteria, patient history, and a careful examination of joint hypermobility using the Beighton scale. But this scale, like much of EDS assessment, is subjective and does not capture the full range of the disorder’s complexity.

The result is a population of patients who often feel unseen and unheard. They may be told their symptoms are psychosomatic or suffer from “anxiety,” a common misdiagnosis in those with hEDS. Women, in particular, face gendered biases that delay proper recognition of their symptoms. The lack of awareness in the broader medical community only adds to the burden.

The Invisible Pain: Living with EDS Day by Day

For those who live with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, each day is a careful negotiation with their body. Chronic pain is a near-universal feature, especially in hEDS, where joints slip out of place with alarming ease. What might seem like a simple movement to most—a stretch, a twist, a bend—can lead to a subluxation or dislocation. The pain can be deep and persistent, often affecting multiple joints simultaneously.

Fatigue is another constant companion. The body must work harder to compensate for the laxity of ligaments and the inefficiency of movement. Many describe a profound sense of exhaustion that sleep does little to alleviate. The energy cost of merely existing is higher when your structural integrity is compromised.

Then there is the gastrointestinal distress. Many people with EDS suffer from irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), gastroparesis, or other motility issues. Autonomic dysfunction, such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), is also commonly associated with EDS, causing dizziness, heart rate irregularities, and fainting spells.

Mental health challenges often follow. Chronic illness takes a toll on the psyche, and the uncertainty of EDS—its flare-ups, its unpredictability, its lack of cure—can lead to anxiety, depression, and isolation. The invisible nature of the disease means that sufferers often feel misunderstood, even by those closest to them.

The Genetic Puzzle: Unraveling the Code

At the heart of EDS lies a genetic mystery. For the rarer types, scientists have identified specific mutations in genes responsible for collagen synthesis or processing. In classical EDS, mutations in COL5A1 and COL5A2 are known culprits. In vascular EDS, it’s COL3A1. Other subtypes are linked to enzymes involved in collagen modification, such as lysyl hydroxylase.

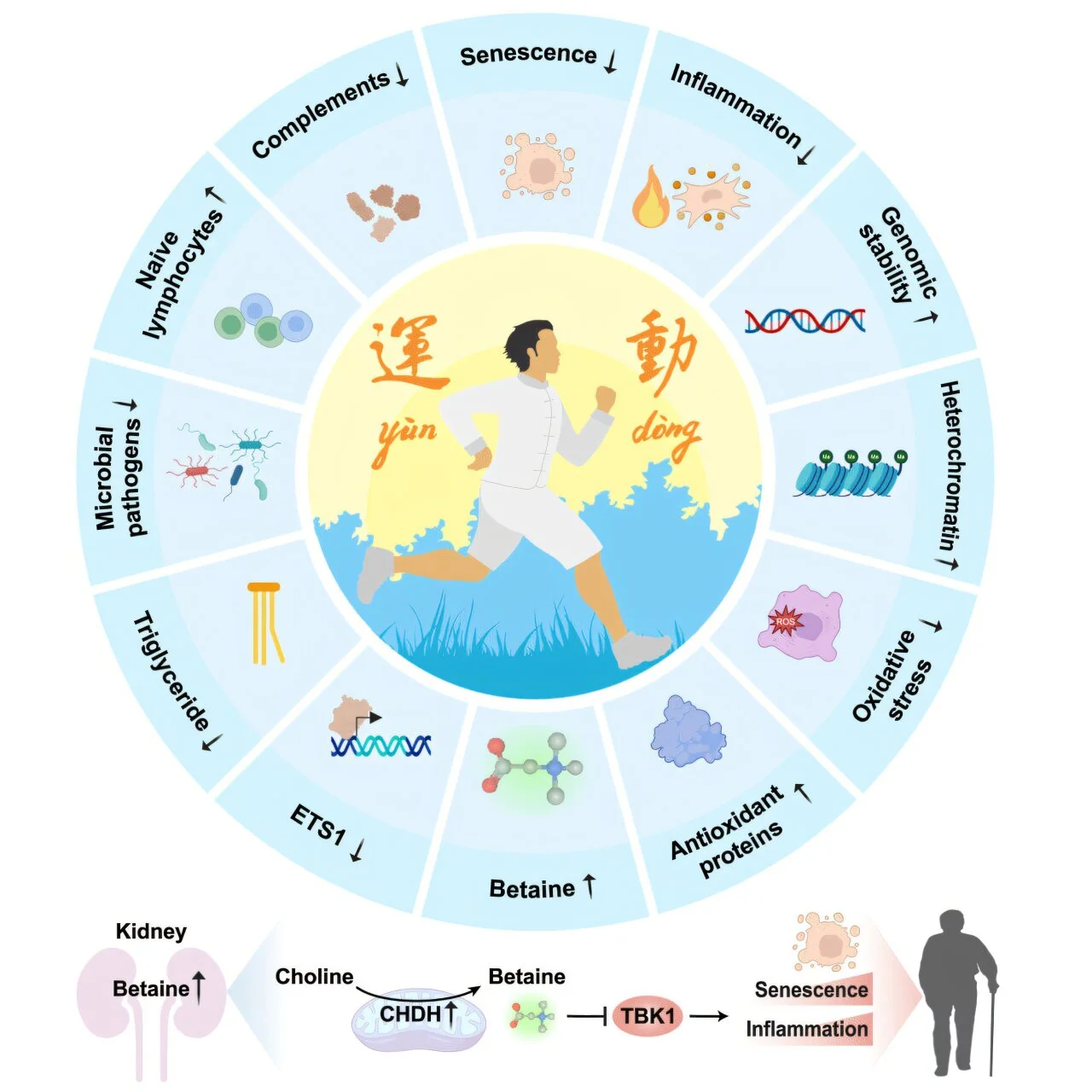

Yet hypermobile EDS remains genetically unexplained. Despite extensive research, no single gene or mutation has been consistently linked to the disorder. This suggests that hEDS might result from multiple genetic factors acting together or from mutations in genes not yet discovered. Environmental triggers and epigenetics might also play a role, adding layers of complexity to the puzzle.

The lack of a genetic test for hEDS has major implications. Without a definitive biomarker, diagnosis relies heavily on clinical criteria, which can be subjective and vary between practitioners. This gray area leaves many patients in diagnostic limbo, unsure whether they truly have EDS or something else entirely.

Treatment Without a Cure: Managing the Unmanageable

Perhaps the most challenging aspect of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is that there is no cure. Treatment focuses on symptom management and quality of life. This often involves a multidisciplinary approach: physical therapy to strengthen muscles and stabilize joints, pain management strategies, gastrointestinal care, cardiovascular monitoring, and sometimes psychological support.

Physical therapy is essential but must be tailored to the individual. Traditional exercises can do more harm than good if they overstretch already lax joints. Therapists trained in hypermobility disorders can help develop safe movement routines that enhance joint stability without triggering dislocations.

Pain management remains a complex issue. Over-the-counter medications may be insufficient, while opioids carry risks of dependence and are often discouraged. Some patients find relief through alternative therapies such as acupuncture, massage, or biofeedback, though results vary. Others turn to assistive devices like braces, compression garments, or mobility aids to reduce strain and prevent injury.

Psychological support is equally important. Living with a chronic, invisible illness can be emotionally exhausting. Support groups, counseling, and cognitive-behavioral therapy can provide vital coping strategies. Education for both patients and families is key—understanding the nature of EDS helps reduce fear and fosters more compassionate care.

The Rise of Awareness: From Obscurity to Advocacy

In recent years, public awareness of Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome has grown, thanks in part to social media, celebrity disclosures, and grassroots advocacy. Online communities have become lifelines for patients seeking information, validation, and connection. These platforms allow people from around the world to share their stories, compare symptoms, and support one another in ways that were unthinkable just a decade ago.

Medical professionals are slowly catching up. Specialized clinics for connective tissue disorders are emerging, and medical schools are beginning to include EDS in their curricula. Organizations like The Ehlers-Danlos Society work tirelessly to promote research, education, and patient care. While the pace of change is slow, the momentum is undeniable.

Yet challenges remain. Misinformation and self-diagnosis are rampant online, sometimes leading people to wrongly assume they have EDS based on flexible joints alone. This undermines the credibility of those genuinely affected and complicates the clinical picture. Clear guidelines and better diagnostic tools are needed to help distinguish true cases from benign joint hypermobility.

The Future of EDS Research: Hope on the Horizon

Scientific interest in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is growing. Advances in genetic sequencing, molecular biology, and biomechanics are opening new avenues for understanding the condition. Researchers are exploring the role of the extracellular matrix, the biomechanical properties of connective tissue, and the intricate signaling pathways involved in collagen production.

There is hope that, in time, a genetic basis for hypermobile EDS will be found. Studies are also examining the relationship between EDS and other comorbidities, including autoimmune disorders, mast cell activation syndrome, and neurological conditions. The goal is a more holistic view of the syndrome—one that reflects its multifaceted reality.

Ultimately, the future of EDS treatment may lie in personalized medicine. By identifying the unique genetic and biochemical profile of each patient, doctors may be able to offer more targeted therapies. Until then, the focus remains on improving quality of life and ensuring that those with EDS are no longer invisible.

A Life Redefined: The Courage of the EDS Community

Living with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is not merely a medical condition; it is a daily act of adaptation and resilience. Those affected by EDS navigate a world not built for bodies that bend too far, stretch too easily, or fall apart without warning. Yet within this struggle lies a profound strength.

The EDS community is one of remarkable courage and solidarity. Patients become experts in their own bodies, advocates for their own care, and educators for those around them. Parents of children with EDS learn to balance vigilance with hope. Doctors who specialize in the condition often do so out of a deep commitment to changing the narrative—from confusion and dismissal to empathy and understanding.

There is something inherently heroic in refusing to be defined by a diagnosis, in choosing to live fully even when the body resists. This is the paradox of EDS: a condition of fragility, yet a source of great inner strength.

Conclusion: The Mystery that Demands Understanding

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome is a biological enigma, a medical puzzle still waiting to be fully solved. It is a reminder of how much we still don’t know about the human body and how our systems can go awry in subtle, far-reaching ways. But it is also a story of perseverance—of people who live with daily pain, fatigue, and uncertainty, and who nonetheless keep going.

In uncovering the mystery of EDS, we do more than explain a syndrome—we illuminate the resilience of the human spirit, the power of scientific inquiry, and the need for compassion in medicine. The more we learn, the more we are called to listen—not just to symptoms, but to stories. And in listening, we begin to understand not just Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, but what it means to truly care for one another.