Beneath the skin, within the silent mechanisms of every cell, lies the potential for a profound betrayal. A betrayal that rewrites cellular instructions, misguides growth, and corrupts order. This betrayal is cancer—and oncology is the science of understanding, diagnosing, and fighting it.

Cancer is one of the oldest known diseases, yet it remains one of the most complex and confounding. It’s not a single illness but a family of diseases that can arise anywhere in the body, taking on different forms, behaviors, and aggressiveness. It’s cunning, evolving to resist treatment, finding refuge in healthy tissue, and returning when we believe it’s gone.

But alongside this dark brilliance of cancer is the relentless pursuit of knowledge—oncology. From ancient descriptions carved into stone to the genomic sequencing of tumors today, oncology represents one of medicine’s most passionate, determined, and innovative battlegrounds.

This article explores oncology not as a collection of clinical terms, but as a dynamic and deeply human story—of biology gone rogue, of medicine in pursuit, and of lives caught in the balance.

The Origins of Oncology: A Battle as Old as Civilization

The word “cancer” comes from the Greek “karkinos,” meaning crab. It was Hippocrates, the father of medicine, who first used the term to describe tumors, noting their crab-like spread and grasp on the body. Though medicine in ancient Greece had no tools to understand cell biology, physicians recognized cancer’s destructive power.

In ancient Egypt, descriptions of breast tumors appear in surgical papyri dating back over 3,500 years. The recommended treatments? Cauterization or surgical excision—tools still used in modified form today. But the understanding of cancer remained limited until the 19th century, when advances in microscopy allowed scientists to peer into tissues and witness the chaotic growth of cancer cells for the first time.

The birth of modern oncology came in the 20th century, with the rise of pathology, radiology, and biochemistry. The realization that cancer is fundamentally a disease of cells—and more specifically, of DNA—revolutionized our understanding.

Today, oncology is an umbrella field encompassing prevention, diagnostics, surgical removal, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, palliative care, and cutting-edge personalized medicine. Yet its roots still draw from ancient observations about what happens when the body’s harmony breaks down.

What Is Cancer, Really?

To understand oncology, we must first understand what cancer is—not just as a concept, but as a biological reality.

At its core, cancer is uncontrolled cell growth. Every cell in our body is programmed to divide, function, and die in a tightly regulated cycle. This cycle ensures that old or damaged cells are replaced and that organs maintain their structure and function.

But sometimes, mutations occur in the DNA of a cell. These mutations may be caused by various factors—radiation, chemicals, viruses, or random errors during replication. Most mutations are harmless, and our body has repair mechanisms that fix them. But when these safeguards fail, and the mutations affect genes involved in cell cycle regulation, the result can be a cell that refuses to stop dividing.

These mutated cells begin to replicate uncontrollably, forming a mass known as a tumor. If the tumor remains localized and non-invasive, it is considered benign. But if it invades nearby tissue, spreads to other parts of the body, and resists apoptosis (programmed cell death), it is deemed malignant—or cancerous.

The most dangerous aspect of cancer is its ability to metastasize, meaning it can travel through the bloodstream or lymphatic system to colonize distant organs. A person may be diagnosed with lung cancer, for example, but the tumor might have originated in the colon or breast.

This ability to adapt, spread, and evolve makes cancer a formidable adversary—and oncology the art and science of deciphering and combating its moves.

Types of Cancer: A Kaleidoscope of Diseases

There is no one “cancer.” Instead, oncology recognizes over 200 different types, classified by the origin of the tissue or cell type. Each type behaves differently, demands unique treatments, and poses distinct challenges.

The major categories include:

Carcinomas – The most common, originating in the skin or tissues that line internal organs (e.g., breast, lung, prostate, colon).

Sarcomas – Arising from connective tissues like bone, muscle, or cartilage.

Leukemias – Cancers of the blood or bone marrow, leading to uncontrolled white blood cell production.

Lymphomas – Cancers of the lymphatic system, which is vital for immune function.

Myelomas – Cancers of plasma cells, which produce antibodies in the immune system.

Each type of cancer is further broken down into subtypes based on genetic mutations, histology (microscopic structure), hormone sensitivity, and molecular markers.

This diversity is what makes oncology so complex. The treatment for one type of cancer might be useless—or even harmful—for another. That’s why oncologists specialize in specific cancer types, and why research must delve into each disease’s unique fingerprint.

Causes and Risk Factors: Why Cancer Happens

Cancer can strike anyone, but not everyone has the same risk. Understanding the causes and risk factors is central to both oncology and prevention.

Some of the most well-established causes include:

Genetic mutations – Some people inherit mutations that predispose them to cancer, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 for breast and ovarian cancer, or mutations in the APC gene for colon cancer.

Lifestyle factors – Smoking is the single most preventable cause of cancer worldwide, linked to lung, throat, bladder, and other cancers. Diet, alcohol, sun exposure, and sedentary lifestyle also play significant roles.

Infections – Certain viruses and bacteria are carcinogenic. Human papillomavirus (HPV) causes cervical cancer. Hepatitis B and C viruses are linked to liver cancer. Helicobacter pylori infection increases stomach cancer risk.

Environmental exposures – Radiation (such as UV rays or X-rays), asbestos, benzene, and other chemicals can cause DNA damage leading to cancer.

Hormones and reproductive factors – Estrogen exposure (early menstruation, late menopause, hormone replacement therapy) has been linked to certain breast cancers.

Age – The risk of cancer increases significantly with age. This is partly due to the accumulation of DNA damage over time and a decrease in immune surveillance.

Yet despite these known risks, many cancers occur without clear cause. That’s what makes oncology as much a mystery as it is a science—unpredictable, personal, and often bewildering.

Diagnosing Cancer: From Suspicion to Confirmation

The path to a cancer diagnosis often begins with symptoms—unusual weight loss, lumps, fatigue, unexplained pain, persistent cough, or abnormal bleeding. But many cancers are silent, progressing without symptoms until they are advanced.

Diagnosis in oncology typically follows a series of steps:

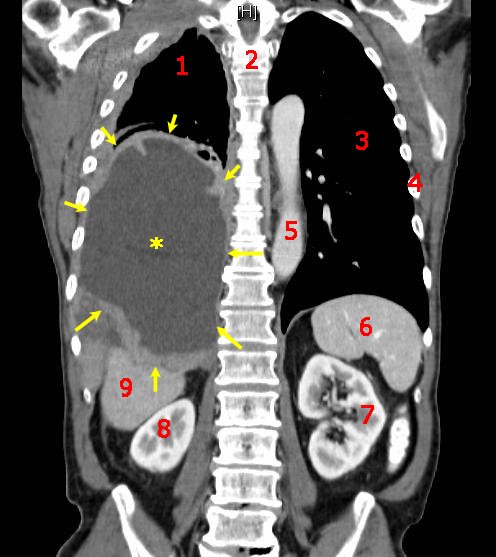

Imaging – Techniques like X-rays, CT scans, MRIs, PET scans, and ultrasounds help visualize tumors, determine their size, location, and spread.

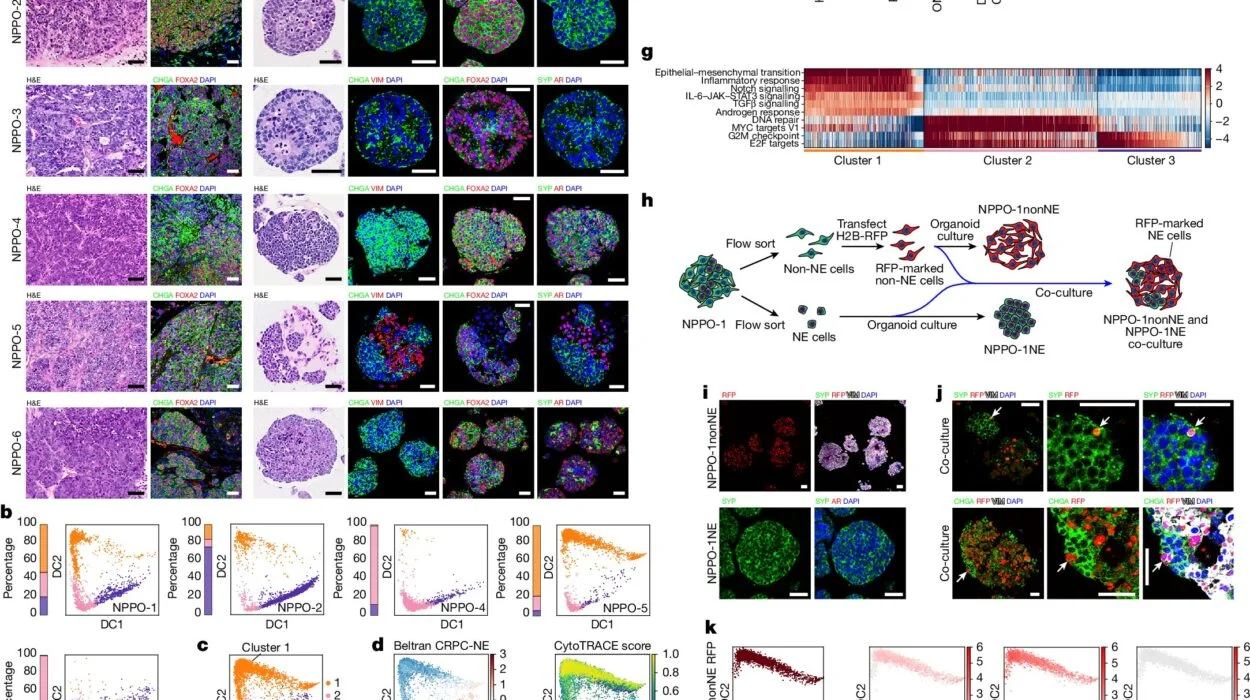

Biopsy – A tissue sample is taken and examined under a microscope. This is the gold standard for cancer diagnosis and allows for precise classification.

Blood tests – Some cancers produce specific substances (tumor markers) that can be detected in blood, such as PSA for prostate cancer or CA-125 for ovarian cancer.

Molecular profiling – Advanced tests analyze the tumor’s DNA, RNA, and protein expression. This information guides targeted therapy and immunotherapy, a cornerstone of modern oncology.

A diagnosis isn’t just a label—it’s a map. It tells oncologists what kind of cancer it is, how aggressive it is, how far it has spread, and how best to fight it.

Staging and Grading: Knowing the Enemy

Once cancer is diagnosed, it must be staged and graded to determine prognosis and treatment strategy.

Staging describes the extent of the disease:

- Stage 0: Pre-cancerous or in situ (localized)

- Stage I: Small, localized tumors

- Stage II-III: Increasing spread to nearby tissues or lymph nodes

- Stage IV: Distant metastasis

Grading refers to how abnormal the cancer cells appear:

- Low-grade tumors resemble normal cells and tend to grow slowly.

- High-grade tumors appear very abnormal and often grow and spread rapidly.

Together, staging and grading help determine the best course of action. A Stage I, low-grade tumor might be curable with surgery alone, while a Stage IV, high-grade cancer may require systemic chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and palliative care.

Cancer Treatment: Weapons in the War

Oncology’s therapeutic arsenal has evolved dramatically over the past century. From the crude surgeries of the 1800s to today’s gene therapies, cancer treatment has become a sophisticated science.

Surgery – Often the first line of treatment when a tumor is localized. The goal is to remove all visible cancer and a margin of healthy tissue.

Radiation therapy – Uses high-energy beams to destroy cancer cells or shrink tumors before surgery. It can be external or internal (brachytherapy).

Chemotherapy – Drugs that kill rapidly dividing cells. While effective, chemotherapy also affects healthy cells (like hair follicles and the gut lining), leading to side effects.

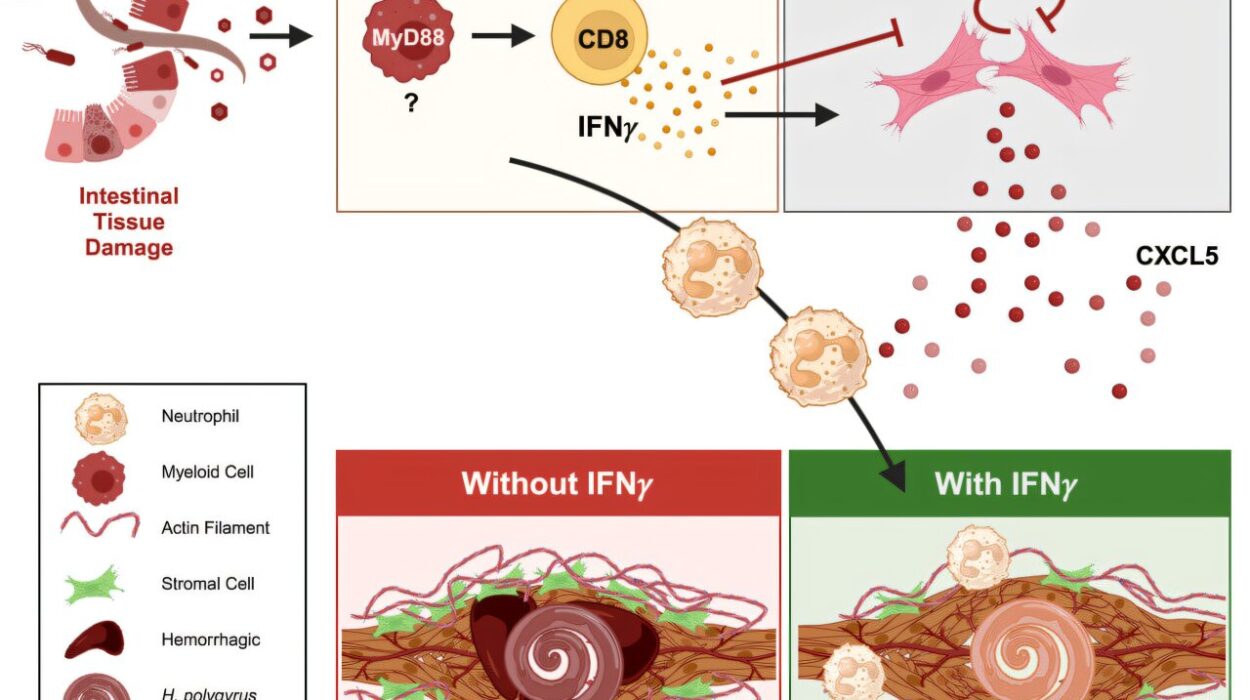

Immunotherapy – One of the most promising recent advances. It activates the patient’s immune system to recognize and attack cancer. Checkpoint inhibitors, CAR-T therapy, and cancer vaccines fall into this category.

Targeted therapy – Drugs designed to target specific molecular abnormalities in cancer cells. For example, HER2 inhibitors in breast cancer or BRAF inhibitors in melanoma.

Hormonal therapy – Used in cancers that are hormone-sensitive, such as breast and prostate cancers. It blocks or reduces hormone levels to slow tumor growth.

Palliative care – Focuses on relief from symptoms and improving quality of life, particularly when cure is not possible.

Oncology today is increasingly personalized. Treatment plans are no longer “one size fits all” but are tailored to the genetic profile of both the patient and the tumor.

Life With and After Cancer: Survivorship and Recovery

Cancer is not just a medical condition—it’s a life-altering experience. Oncology must address the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions of cancer care.

Survivorship is an evolving field within oncology. As treatments improve, more people live years—even decades—after a cancer diagnosis. But survivorship is not just survival; it’s about living well.

Cancer survivors may face long-term side effects: fatigue, cognitive issues, heart or lung problems, or risk of second cancers. They also grapple with anxiety, depression, fear of recurrence, and disruptions in work or relationships.

Oncologists now collaborate with psychologists, nutritionists, physical therapists, and social workers to provide holistic care. Follow-up visits, screenings, and support groups are essential parts of survivorship planning.

The Future of Oncology: Hope on the Horizon

Despite its challenges, oncology is one of the most rapidly advancing fields in medicine. Breakthroughs happen every year.

Precision medicine is transforming treatment. Tumors are now sequenced to identify vulnerabilities, allowing therapies to be matched like a lock and key.

Liquid biopsies—blood tests that detect cancer DNA fragments—are improving early detection and monitoring.

Artificial intelligence is being used to analyze scans, predict outcomes, and discover new drug targets.

Cancer vaccines are being developed, not just to prevent cancers like cervical and liver, but to treat existing tumors by teaching the immune system to attack them.

Gene editing tools like CRISPR may one day correct mutations at their source.

With every clinical trial, every lab discovery, and every patient’s journey, the frontier of oncology moves forward.

Conclusion: The Fight That Defines Us

Cancer is a mirror—a reflection of our biology’s complexity, vulnerability, and resilience. It teaches us about the limits of control, the power of hope, and the strength found in struggle.

Oncology, as a discipline, is not just about eradicating tumors. It’s about understanding the human body and mind in their most fragile and powerful forms. It’s about relationships—between cells, between doctor and patient, between fear and courage.

In every hospital, clinic, and lab, the fight continues. And though cancer may seem like the ultimate adversary, oncology is proof that human determination is just as relentless.

And in that struggle, we find not only science—but something profoundly human.