Astronomers have long known that novae burst into existence with explosive speed, lighting up the sky in a single bright flash before fading back into darkness. But until now, the earliest moments of these eruptions have been little more than guesswork. They unfolded too quickly, too chaotically, and too far away to be seen clearly. What scientists observed was only a point of light, a distant shimmer holding its secrets tight.

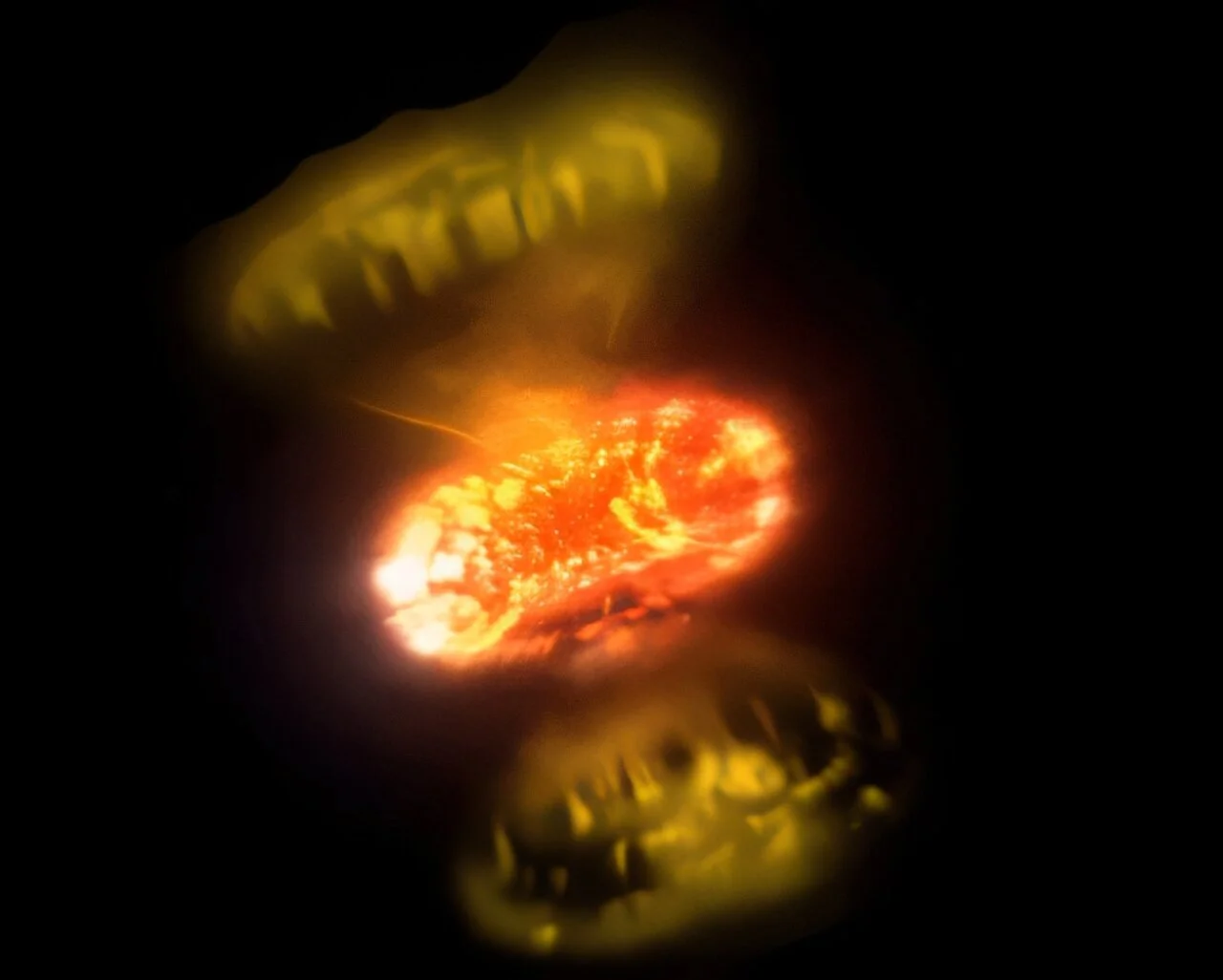

That changed when an international team used the extraordinary power of the CHARA Array in California to capture two nova explosions just days after they ignited. The results revealed something extraordinary. The explosions were not simple, symmetric blasts but tangled dramas of clashing flows, shifting structures and surprising delays. The universe, it seemed, had been hiding a far more intricate story.

“The images give us a close-up view of how material is ejected away from the star during the explosion,” said Georgia State’s Gail Schaefer, director of the CHARA Array. “Catching these transient events requires flexibility to adapt our nighttime schedule as new targets of opportunity are discovered.”

With these images, astronomers finally stepped from speculation into direct observation, watching stellar detonation in real time as if witnessing fire spread through the universe’s dark forest.

When a White Dwarf Breathes Fire

Novae begin with quiet theft. A dense white dwarf tugs material off a companion star, gathering the stolen gas until the pressure and heat at its surface trigger an unstoppable nuclear reaction. The outer layers erupt. The star brightens dramatically. But for all their intensity, these early moments have remained blurry. Telescopes simply could not resolve the structures forming inside the explosion.

Interferometry changed that. By combining light from multiple telescopes, the CHARA Array created a level of sharpness capable of piercing the expanding cloud. Within days of each 2021 explosion, the team managed to capture crisp images of the material flying outward, hour by hour.

“Instead of seeing just a simple flash of light, we’re now uncovering the true complexity of how these explosions unfold. It’s like going from a grainy black-and-white photo to high-definition video,” said Elias Aydi, lead author of the study and a professor at Texas Tech University.

These images held surprises—shocks, twists, changing shapes, and even long pauses as the stars gathered themselves for a second, delayed burst. Suddenly, nova eruptions were no longer singular explosions but unfolding narratives.

Two Novae, Two Wildly Different Lives

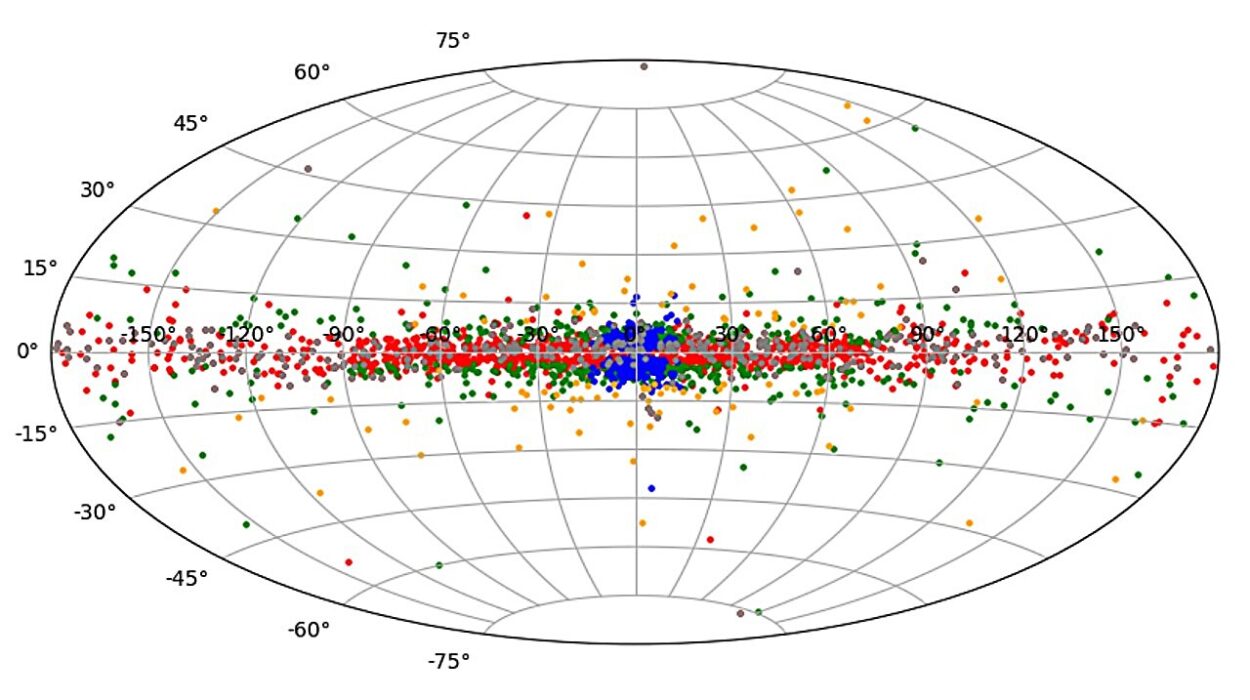

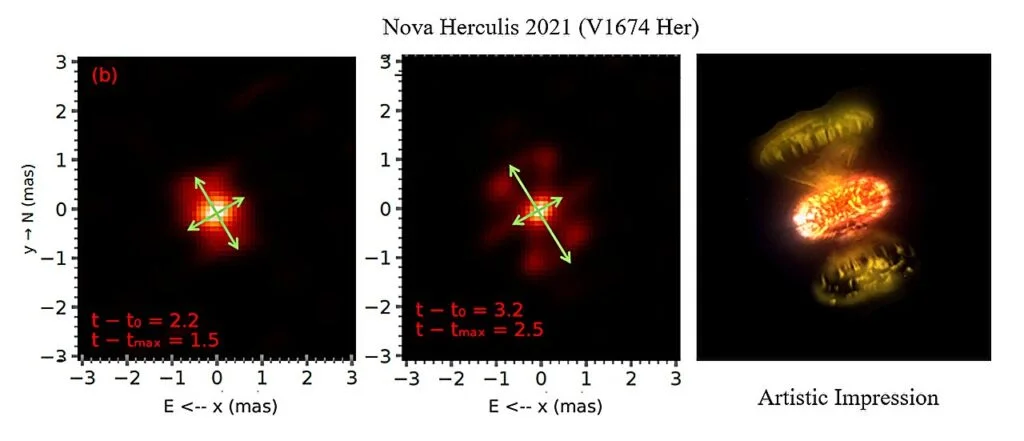

The first nova, V1674 Herculis, lived fast. It brightened and faded within days, one of the quickest on record. But inside that speed lay astonishing complexity. Images revealed not one but two perpendicular outflows of gas, each erupting in different directions. These interacting flows created powerful shocks, and as they appeared in the CHARA images, NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope detected high-energy gamma rays from the same event. A cosmic cause-and-effect relationship unfolded with perfect timing.

The nova was doing more than exploding. It was colliding with itself. Its different outflows met and crashed, turning their violent meeting points into miniature particle accelerators. The images and gamma-ray detections matched each other moment by moment, giving scientists their first direct glimpse of how these shocks are born.

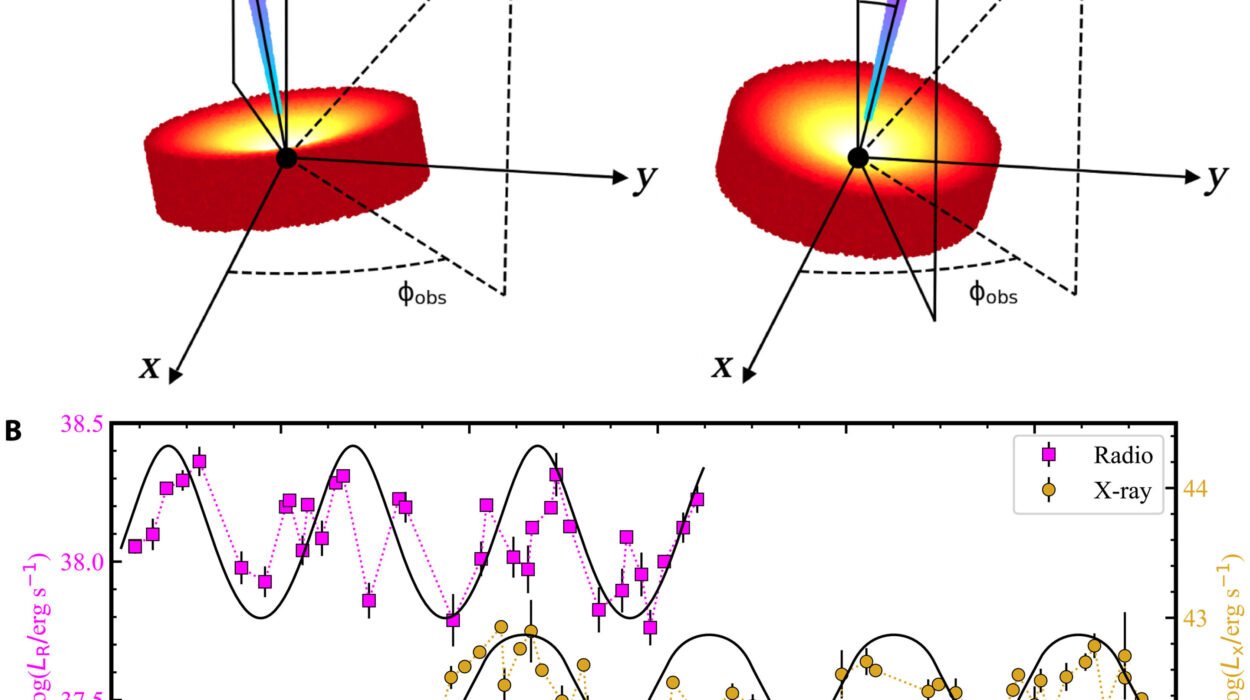

The second nova, V1405 Cassiopeiae, told a very different story. Instead of exploding immediately, it hesitated. For more than 50 days, it held onto its outer layers, defying expectations. Only then did it finally expel the delayed material, launching new shocks into surrounding space. When that delayed blast arrived, Fermi once again saw gamma rays, confirming that these newly triggered shocks were as energetic as the first.

With these two novae, astronomers realized that the universe was capable of crafting vastly different eruption styles—swift, complex, multi-directional blasts or slow, brooding buildups with sudden endings. The neat textbook version of a nova was gone.

Seeing Structures Hidden for Centuries

The breakthroughs were made possible by the same technique that once allowed humanity to glimpse the black hole at the center of our galaxy. Interferometry stitched together the light of multiple telescopes until they behaved like one giant lens, powerful enough to capture tiny structures forming in expanding cosmic smoke.

Spectra from observatories such as Gemini added an essential second layer, showing the chemical fingerprints of the gas as it evolved. When new shapes appeared in the interferometric images, new features appeared in the spectra at the same moments. Two independent tools, working in harmony, painted a single story.

“This is an extraordinary leap forward,” said John Monnier, professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan and an expert in interferometric imaging. “The fact that we can now watch stars explode and immediately see the structure of the material being blasted into space is remarkable. It opens a new window into some of the most dramatic events in the universe.”

What had been invisible for centuries was now unfolding with cinematic clarity.

What These Explosions Teach Us About Extreme Physics

The discovery carries powerful implications. For years, NASA’s Fermi telescope has detected gamma rays from novae—more than twenty in its first fifteen years. But without clear images, scientists could only hypothesize how those gamma rays formed. Now the connection is undeniable. Shocks created by colliding outflows or delayed ejections produce the high-energy radiation.

“Novae are more than fireworks in our galaxy—they are laboratories for extreme physics,” said Professor Laura Chomiuk of Michigan State University. “By seeing how and when the material is ejected, we can finally connect the dots between the nuclear reactions on the star’s surface, the geometry of the ejected material and the high-energy radiation we detect from space.”

The study also challenges a long-held assumption. Novae were thought to be single, impulsive events. A star ignites, material blasts outward and the story ends. But the new images reveal something richer. There can be multiple expulsions. Outflows can collide. Entire shells of material can wait silently for weeks before being flung into space. A nova is not a moment. It is a sequence.

“This is just the beginning,” Aydi said. “With more observations like these, we can finally start answering big questions about how stars live, die and affect their surroundings. Novae, once seen as simple explosions, are turning out to be much richer and more fascinating than we imagined.”

Why This Research Matters

Stars are the engines of the universe. Their explosions seed galaxies with new elements, shape interstellar gas and influence how future stars and planets form. To understand novae is to understand one of the key ways stars shake their surroundings.

These new observations reveal novae not as simple detonations but as dynamic, evolving systems. Their multiple outflows explain the shock waves that create gamma rays. Their delayed expulsions show that surface reactions can unfold in stages. Their detailed structures allow scientists to map precisely how stellar debris moves and collides.

By watching novae in real time, astronomers now have a direct path to exploring shock physics, particle acceleration and the fundamental processes that power some of the most energetic events in the Milky Way. For the first time, the complex choreography of these eruptions is visible—and its lessons extend far beyond a single star.

The universe has always been explosive. Now, at last, we can see how those explosions truly unfold.

More information: Elias Aydi et al, Multiple outflows and delayed ejections revealed by early imaging of novae, Nature Astronomy (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-025-02725-1