For nearly a hundred years, astronomers have known something astonishing: the universe is expanding. Galaxies are drifting apart, carried along by the stretching fabric of space itself. But one stubborn question refuses to settle. Exactly how fast is that expansion happening?

The answer is wrapped inside a single number known as the Hubble constant. It sounds simple—just a rate. Yet this number has become one of the most fiercely debated quantities in modern cosmology. Different methods of measuring it disagree, and that disagreement has grown so sharp that it challenges the very foundations of the standard model of cosmology.

Now, a team of researchers from the Technical University of Munich, Ludwig Maximilians University, and the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics and Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics may have found a new way forward. Their approach doesn’t rely on climbing cosmic ladders or peering into the ancient afterglow of the Big Bang. Instead, it begins with a rare and dazzling cosmic explosion nicknamed SN Winny.

A Supernova That Shouldn’t Be There—Five Times Over

The supernova’s official name is SN 2025wny, but the researchers affectionately call it SN Winny. It lies an unimaginable 10 billion light-years away. Even more remarkable, it belongs to a rare class of superluminous supernovae, stellar explosions far brighter than typical ones.

But its brightness is not the only surprise.

When astronomers looked toward it, they did not see one explosion. They saw five.

The same supernova appears five separate times in the night sky, like a cosmic firework frozen mid-burst. This is not because five stars exploded. It is because of a phenomenon known as gravitational lensing.

Between Earth and SN Winny sit two foreground galaxies. As the supernova’s light journeys toward us, the immense gravity of these galaxies bends and redirects it. The light is forced along different paths through space, like streams splitting around a rock in a river.

Because these paths are not identical in length, the light from the explosion does not arrive all at once. Instead, it reaches Earth at slightly different times, producing five separate images of the same event.

It is beautiful. It is strange. And it is profoundly useful.

Chasing a One-in-a-Million Alignment

Finding such a system is extraordinarily unlikely. The chance of discovering a superluminous supernova perfectly aligned with a suitable gravitational lens is estimated to be lower than one in a million.

The team, led by Sherry Suyu, Associate Professor of Observational Cosmology at TUM and Fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, spent six years searching. They compiled a list of promising gravitational lenses, waiting for the right cosmic explosion to appear behind one of them.

In August 2025, it happened. SN Winny matched exactly with one of their predicted lenses.

It was the kind of moment scientists dream about: years of patient preparation meeting a rare cosmic gift.

Painting the First High-Resolution Portrait

Gravitationally lensed supernovae are so rare that only a handful of such measurements have ever been attempted. And their accuracy depends on something crucial: how well scientists can measure the mass distribution of the galaxies doing the lensing.

Mass determines how strongly light bends. If the mass model is wrong, the calculation of the Hubble constant will be wrong too.

To refine their understanding, team members from MPE and LMU turned to the Large Binocular Telescope. Located in Arizona, this telescope uses two 8.4-meter mirrors and an advanced adaptive optics system that corrects for the blurring effects of Earth’s atmosphere.

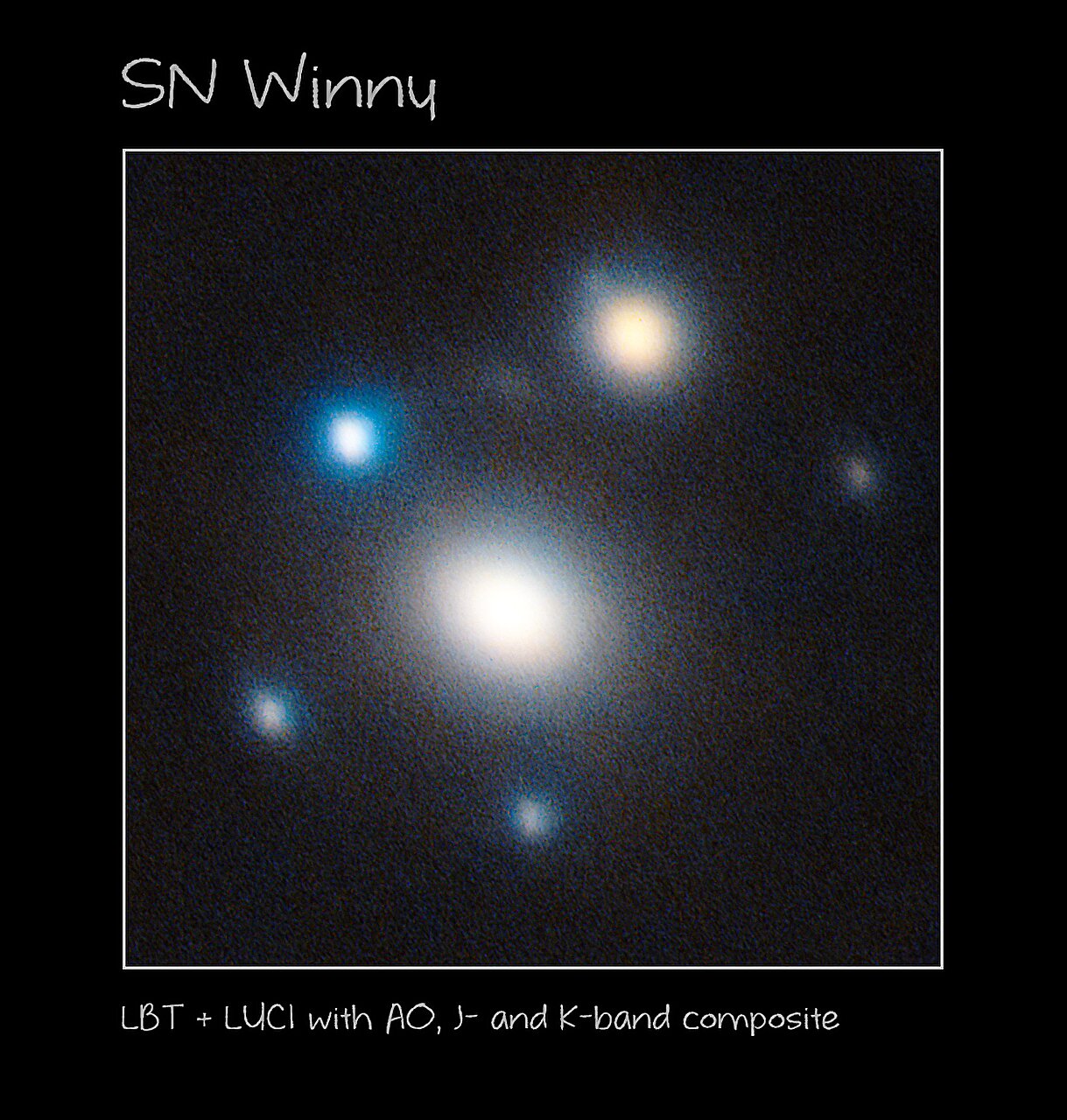

The result was historic: the first high-resolution color image of this system ever published.

In the image, two foreground galaxies sit at the center. Around them glow five bluish points—the five copies of SN Winny—arranged in a pattern reminiscent of an exploding firework. This configuration is highly unusual. Most galaxy-scale lens systems produce only two or four images. Five is rare.

Using the precise positions of all five copies, junior researchers Allan Schweinfurth from TUM and Leon Ecker from LMU built the first detailed model of the lens mass distribution.

Their analysis revealed something encouraging. The two galaxies show overall smooth and regular light and mass distributions, suggesting they have not collided in the past, despite appearing close together in the sky. That simplicity matters. A clean, uncomplicated lens is far easier to model accurately.

And accuracy is everything.

The Puzzle Called Hubble Tension

The urgency behind this work lies in a growing cosmological mystery known as the Hubble tension.

For years, scientists have relied on two primary methods to measure the Hubble constant. Both are sophisticated. Both are precise. And both give different answers.

The first is the cosmic distance ladder. This “local method” measures distances to nearby galaxies step by step. Astronomers use objects of known brightness to estimate distances, then compare those distances with how fast galaxies appear to be moving away. Each step depends on careful calibration. But because it is a multi-step process, small uncertainties can accumulate, subtly shifting the final result.

The second method looks far deeper into the past. It studies the cosmic microwave background, the faint afterglow of the Big Bang. By modeling the early universe and projecting forward, scientists calculate what today’s expansion rate should be. This approach is extremely precise. But it depends heavily on assumptions about how the universe evolved over billions of years. If those assumptions are incomplete or flawed, the result may be skewed.

The disagreement between these two methods has become one of the most pressing issues in cosmology. The universe appears to expand at one rate when measured nearby, and at a different rate when inferred from its earliest light.

Something does not add up.

A New Path: Measuring Time Itself

This is where SN Winny enters the story.

A gravitationally lensed supernova offers a third, independent method of measuring the Hubble constant. Instead of climbing a ladder of distances or modeling the early universe, scientists measure the time delays between the multiple images of the explosion.

When the supernova brightens and fades, each of its five copies does so at slightly different times. By carefully tracking these delays and combining them with the precisely modeled mass distribution of the lensing galaxies, researchers can directly calculate the expansion rate of the universe.

As Stefan Taubenberger, a leading member of Suyu’s team and first author of the supernova identification study, explains, this approach is essentially a one-step method. Unlike the cosmic distance ladder, it does not rely on multiple calibration stages. And unlike the cosmic microwave background method, it does not depend on detailed assumptions about the early universe.

Its uncertainties are fewer—and entirely different.

In a field where independent confirmation is priceless, this matters deeply.

Watching the Firework Fade

Astronomers around the world are now observing SN Winny using both ground-based and space-based telescopes. Every flicker of light, every change in brightness, is a clue.

As the supernova evolves, the timing of each of its five images will be measured with extraordinary precision. Those measurements, combined with the detailed mass model of the lensing galaxies, will yield a new estimate of the Hubble constant.

It is a patient process. The light that began its journey 10 billion years ago is now being used as a cosmic stopwatch.

Why This Matters

At first glance, measuring the universe’s expansion rate may seem abstract. A number on a page. A debate among specialists.

But the Hubble constant is not just a parameter. It is a key to understanding the universe’s history, structure, and ultimate fate. If different methods continue to disagree, it could signal that something fundamental in our cosmological model is incomplete.

SN Winny offers something rare: an independent test. A fresh perspective. A way to measure the universe’s growth without relying on the same assumptions as before.

The system’s unusual simplicity—the smooth lens galaxies, the clean five-image configuration—makes it an especially promising laboratory. If this method confirms one side of the Hubble tension, it strengthens that measurement. If it lands somewhere unexpected, it could deepen the mystery.

Either way, it pushes science forward.

For nearly a century, we have known the universe is expanding. Now, thanks to a superluminous explosion that appears five times in the sky, we may soon know its speed with greater clarity than ever before.

Sometimes, it takes a one-in-a-million alignment across billions of light-years to illuminate a question that has haunted us for generations.

Study Details

Stefan Taubenberger et al, HOLISMOKES XIX: SN 2025wny at z=2, the first strongly lensed superluminous supernova, arXiv (2025). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2510.21694

L. R. Ecker et al, HOLISMOKES XX. Lens models of binary lens galaxies with five images of Supernova Winny, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2602.16620