For centuries, Uranus drifted through our understanding as a distant, pale world—icy, tilted, and mysterious. Astronomers could measure its orbit, glimpse its storms, and detect its strange magnetic field. But one part of the planet remained almost entirely hidden: its upper atmosphere, a region high above the clouds where temperature, charged particles, and magnetic forces dance in ways no one had ever mapped in detail.

Now, for the first time, an international team of astronomers has peeled back that invisible layer. Using the James Webb Space Telescope and its powerful NIRSpec instrument, they have created the most detailed portrait yet of Uranus’s upper atmosphere—revealing how temperature and charged particles change with height, and how the planet’s unusual magnetic field sculpts its glowing auroras.

The results, published in Geophysical Research Letters, mark a turning point in our understanding of this distant ice giant.

Watching a Planet Turn

On 19 January 2025, the team pointed Webb toward Uranus and watched. For 15 hours, nearly a full rotation of the planet, the telescope gathered delicate signals of light from high above the cloud tops. These weren’t bright, obvious features. They were faint glows from molecules in the thin air thousands of kilometers above the surface.

The observations were part of JWST General Observer program 5073, led by H. Melin of Northumbria University. But it was Paola Tiranti, also from Northumbria University in the United Kingdom, who led the effort to transform those subtle signals into something never seen before: a three-dimensional map of Uranus’s upper atmosphere.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to see Uranus’s upper atmosphere in three dimensions,” Tiranti explained. Thanks to Webb’s extraordinary sensitivity, the team could trace how energy moves upward through the planet’s atmosphere and even detect the influence of its lopsided magnetic field.

For the first time, Uranus was no longer just a flat disk in a telescope. It had depth.

Climbing Five Thousand Kilometers Above the Clouds

The region the team explored stretches up to 5,000 kilometers above Uranus’s cloud tops. This high-altitude realm is known as the ionosphere, where the atmosphere becomes ionized and interacts strongly with the planet’s magnetic field. Here, atoms and molecules can lose or gain electrons, becoming charged particles that respond to invisible magnetic forces.

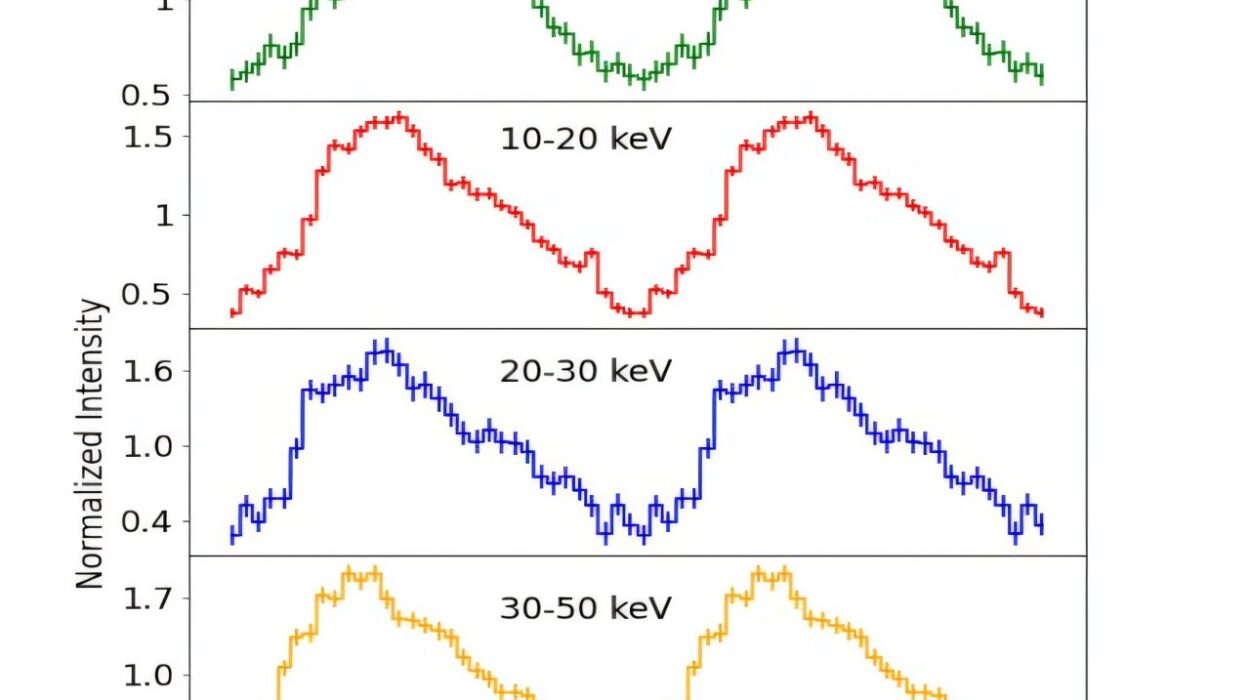

By carefully analyzing Webb’s data, the researchers mapped both the temperature and the density of ions at different heights.

What they found was not uniform or simple.

Temperatures in the upper atmosphere reach their peak between 3,000 and 4,000 kilometers above the clouds. Meanwhile, the density of ions—the concentration of charged particles—reaches its maximum much lower, around 1,000 kilometers.

These measurements reveal a layered and dynamic structure. Heat and charged particles are not distributed evenly. Instead, they vary with altitude and even with longitude, shifting across the planet in ways tied directly to its magnetic field.

This wasn’t just a snapshot. It was a vertical cross-section of a living, breathing planetary system.

A World That Is Still Cooling

There was another surprise hidden in the data.

Uranus’s upper atmosphere is still cooling.

The team measured an average temperature of about 426 kelvins, or roughly 150°C. That might sound extremely hot, but in the context of Uranus’s upper atmosphere, it is cooler than values recorded by earlier ground-based telescopes and spacecraft.

In fact, the cooling trend appears to have begun in the early 1990s and is continuing today. Webb’s measurements confirm that this decades-long decline is still underway.

That steady drop in temperature raises deeper questions about how Uranus distributes and loses energy. Ice giants like Uranus do not behave exactly like gas giants, and understanding how heat moves through their atmospheres is essential to understanding their nature.

For decades, scientists could only guess. Now they have direct evidence.

The Strange Dance of the Auroras

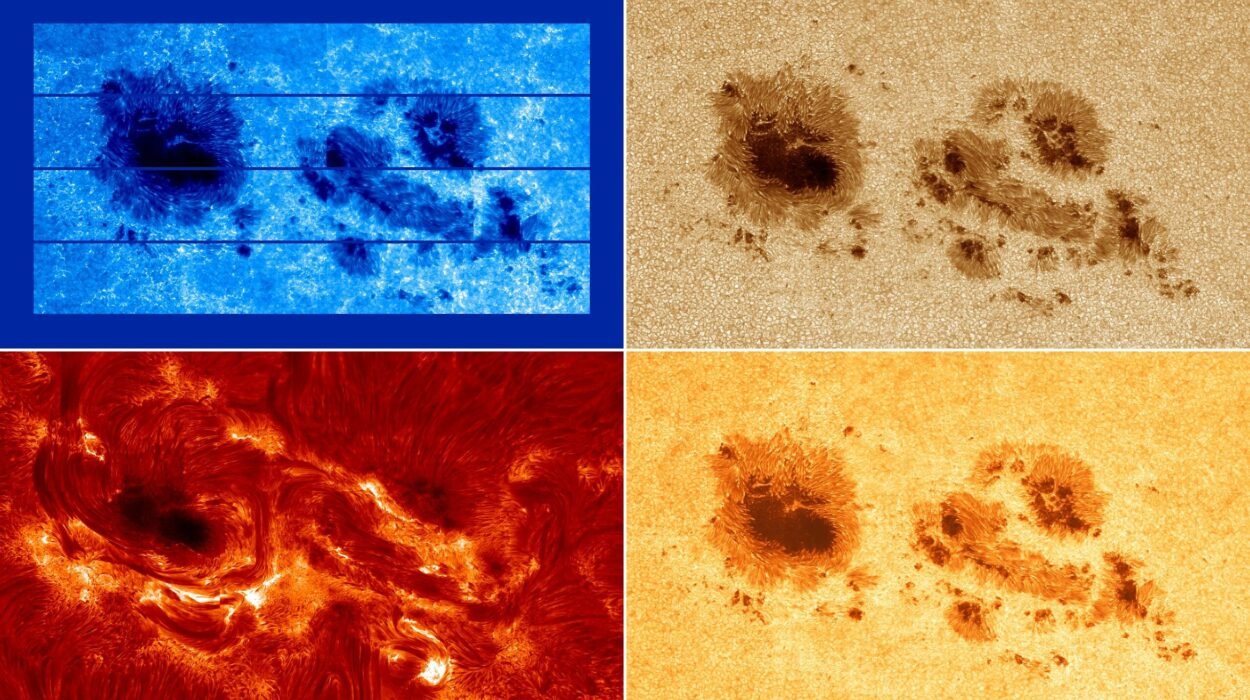

Perhaps the most visually striking discovery involves Uranus’s auroras—the glowing bands that appear when charged particles collide with the atmosphere near the magnetic poles.

Webb detected two bright auroral bands near Uranus’s magnetic poles. But the story did not end there.

Between these glowing regions, the researchers found a distinct depletion in emission and ion density—a darkened area where the expected glow and charged particles were noticeably reduced. This feature is likely linked to transitions in the planet’s magnetic field lines.

Similar darkened regions have been observed at Jupiter, where the geometry of the magnetic field controls how charged particles travel through the upper atmosphere. On Uranus, the pattern appears to be shaped by something even stranger.

Uranus’s magnetosphere is one of the most unusual in the solar system. Its magnetic field is both tilted and offset from the planet’s rotation axis. That means the auroras do not simply sit neatly at the poles. Instead, they sweep across the surface in complex, shifting patterns.

Webb has now revealed how deeply those magnetic effects penetrate. The field does not just shape the auroras at the top of the atmosphere; it influences the vertical structure of temperature and ion density thousands of kilometers above the clouds.

The magnetic field leaves fingerprints everywhere.

Seeing Energy in Motion

With these observations, scientists can now trace how energy flows upward through Uranus’s atmosphere. Heat rises. Charged particles move. Magnetic forces twist and guide them.

The longitudinal variations observed in the data—changes across different parts of the planet—are directly linked to the complex geometry of the magnetic field. The upper atmosphere is not static. It responds constantly to shifting magnetic conditions.

By mapping these changes, the team has provided the clearest picture yet of how Uranus distributes energy in its upper layers.

And that matters more than it might first appear.

Why This Discovery Matters

Uranus is classified as an ice giant, a type of planet distinct from both rocky worlds like Earth and gas giants like Jupiter. Understanding how energy moves through its atmosphere is essential to understanding what makes ice giants unique.

By revealing the detailed vertical structure of Uranus’s upper atmosphere, Webb has given scientists a new tool for studying not only this planet, but others like it.

The findings are described as a crucial step toward characterizing giant planets beyond our solar system. Many of the worlds discovered around distant stars are similar in size and composition to Uranus. Yet until now, even our own nearby example remained only partially understood.

If we cannot fully explain the energy balance of Uranus, how can we hope to interpret the atmospheres of distant planets orbiting other suns?

This research changes that. It provides real measurements of temperature, ion density, and auroral structure. It confirms that Uranus is still cooling. It shows how a tilted, offset magnetic field shapes the upper atmosphere in three dimensions.

In doing so, it transforms Uranus from a distant enigma into a laboratory for understanding planetary physics.

For decades, the planet’s upper atmosphere was an unseen frontier. Now, thanks to the sensitivity of the James Webb Space Telescope and the precision of NIRSpec, we can finally see how this strange world breathes, cools, and glows.

In mapping Uranus’s invisible heights, astronomers have taken a decisive step toward understanding not just one planet, but the broader story of how giant worlds manage their energy across the cosmos.

Study Details

Paola I. Tiranti et al, JWST Discovers the Vertical Structure of Uranus’ Ionosphere, Geophysical Research Letters (2026). DOI: 10.1029/2025gl119304