The pursuit of high-speed, energy-efficient computing has led scientists to look beyond the silicon chip and toward the fundamental properties of light. In the world of optical computing, information isn’t processed through moving electrons, but through the elegant dance of photons. Specifically, diffractive optical networks utilize passive, structured phase masks to manipulate light as it propagates through space, allowing for massive, large-scale parallel computation at the speed of light. Yet, for all their potential, these systems have long been haunted by a ghost in the machine: the gap between theory and reality.

The struggle between digital dreams and physical reality

For years, the standard way to prepare these optical systems was through model-based simulations. Scientists would build a “digital twin” of the hardware—a perfect mathematical representation of how light should behave. They would train the system in this virtual world and then try to port that “intelligence” onto the physical device. However, the real world is messy. Even the most sophisticated simulations struggle to account for the tiny misalignments, unpredictable noise, and subtle model inaccuracies that exist in a laboratory setting. When a system trained in a perfect vacuum of code meets the imperfect reality of hardware, its performance often falters.

The challenge was clear: how do you teach a machine to think when you cannot perfectly describe the environment it lives in? A team of researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) decided that instead of trying to perfect the map, they would teach the machine to navigate the terrain by feel. They moved away from the reliance on a digital twin and toward a revolutionary model-free in situ training framework.

Learning to see through the eyes of the machine

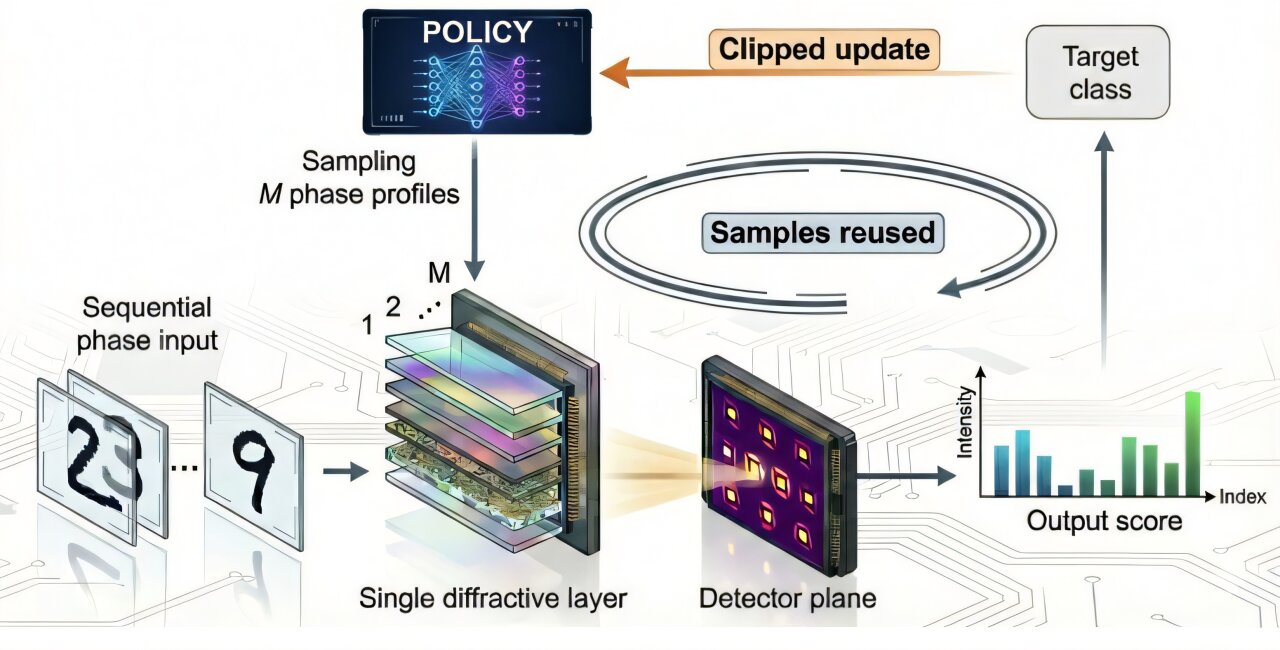

At the heart of this breakthrough is a reinforcement learning algorithm known as proximal policy optimization, or PPO. Typically used in complex software environments, PPO is celebrated for its stability and sample efficiency. The UCLA team, led by Aydogan Ozcan, realized that this algorithm could be the bridge between abstract math and physical light. Instead of feeding the system a set of rules about how physics works, they allowed the diffractive optical processor to learn directly from its own real optical measurements.

This in situ process means the training happens “on-site,” directly on the hardware. The system makes a change to its diffractive features, observes the result through a sensor, and adjusts its strategy based on the feedback. It is a process of learning from experience rather than following a pre-written script. As Professor Ozcan noted, the goal was to stop trying to simulate complex optical behavior perfectly and instead allow the device to learn from its own experiments. Because PPO reuses measured data for multiple update steps while keeping a tight leash on how much the “policy” changes at once, the training remains fast and reliable even in noisy optical environments.

A journey through the fog of the unknown

To prove that this “physics-blind” approach could actually work, the researchers put their system through a series of grueling experimental tests. One of the most striking demonstrations involved a random, unknown diffuser—essentially a piece of material that scatters light in a chaotic, unpredictable way. Without knowing anything about the properties of the diffuser or the underlying physics of the setup, the PPO-driven system successfully learned how to focus optical energy through the chaos.

The system wasn’t just guessing; it was exploring the optical parameter space with a level of efficiency that surpassed standard policy-gradient optimization. The researchers watched as the processor adapted, finding the precise configuration needed to pierce through the distortion. This wasn’t a one-off success. The same framework was applied to the complex task of hologram generation and the delicate work of aberration correction, proving that the model-free approach was versatile enough to handle various optical hurdles.

Teaching light the language of numbers

The ultimate test of a computer, however, is its ability to process information. The UCLA team decided to see if their light-based processor could learn to recognize human handwriting. Using the in situ training framework, the device was tasked with classifying handwritten digits. During the experiment, the processor received images of numbers and had to sort them correctly based on the resulting light patterns.

As the training progressed, a fascinating transformation occurred. The output patterns—the “answers” written in light—began to shift. They became clearer, sharper, and more distinct for each different input number. Without any digital processing to help it, the optical hardware itself learned to distinguish a “3” from an “8.” It was computing through physical adaptation. This demonstrated that the system could not only overcome physical noise but could also organize itself to perform high-level logic tasks entirely within the realm of optics.

Why this shift in perspective matters

This research marks a fundamental shift in how we build “intelligent” hardware. By removing the need for a detailed physical model, we open the door to a new generation of intelligent physical systems that are truly autonomous. These devices don’t need a human to explain the laws of physics to them; they can sense their environment, adapt to their own imperfections, and compute solutions in real-time.

The implications of this model-free approach extend far beyond a single lab at UCLA. Because it is scalable and resilient to unstable behavior, this framework can be applied to a vast array of physical systems that provide feedback. In the near future, this could lead to the development of ultra-fast photonic accelerators for AI, nanophotonic processors that fit on a tiny chip, and adaptive imaging systems that can see through murky environments with ease. By teaching machines to learn from the light itself, we are moving toward a world of real-time optical AI hardware that is faster, smarter, and more adaptable than anything silicon alone could ever achieve.

Study Details

Yuhang Li et al, Model-free optical processors using in situ reinforcement learning with proximal policy optimization, Light: Science & Applications (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41377-025-02148-7