In the world of materials science, some stories read like tales of redemption. Barium titanate, a compound discovered in 1941, has long been known as a powerhouse of potential. On paper, it was extraordinary—its electro-optic properties made it one of the best materials known for converting electrical signals into light. Yet, for decades, it sat on the sidelines.

In practice, it was too difficult to manufacture, too unstable, and too inconsistent for large-scale industrial use. As technology advanced, another material—lithium niobate—quietly took center stage. It was easier to work with, more predictable, and good enough to power a generation of optical devices. Barium titanate, despite its brilliance, became a “what if” in the story of materials innovation.

Now, researchers at Penn State have given this classic material a second chance—and this time, it could reshape the future of computing itself.

Bridging Two Worlds: Electricity and Light

Electro-optic materials like barium titanate are the translators of the modern world. They bridge two fundamental languages—electricity and light—by converting electronic signals into photons. In simple terms, they turn the flow of electrons in a circuit into light waves that can travel through optical fibers.

This process may sound technical, but it underpins much of modern communication. Every time you stream a video, send an email, or join a video call, this electrical-to-optical conversion is happening at lightning speed.

But there’s a problem: the conversion process is still far from perfect. It wastes energy and limits the performance of both data networks and emerging technologies like quantum computers.

That’s where the Penn State team’s breakthrough comes in. By reshaping barium titanate into a form it’s never taken before—an ultrathin, “strained” film—they’ve unlocked new levels of efficiency that could revolutionize the way information moves through our digital world.

Strain: The Secret Ingredient

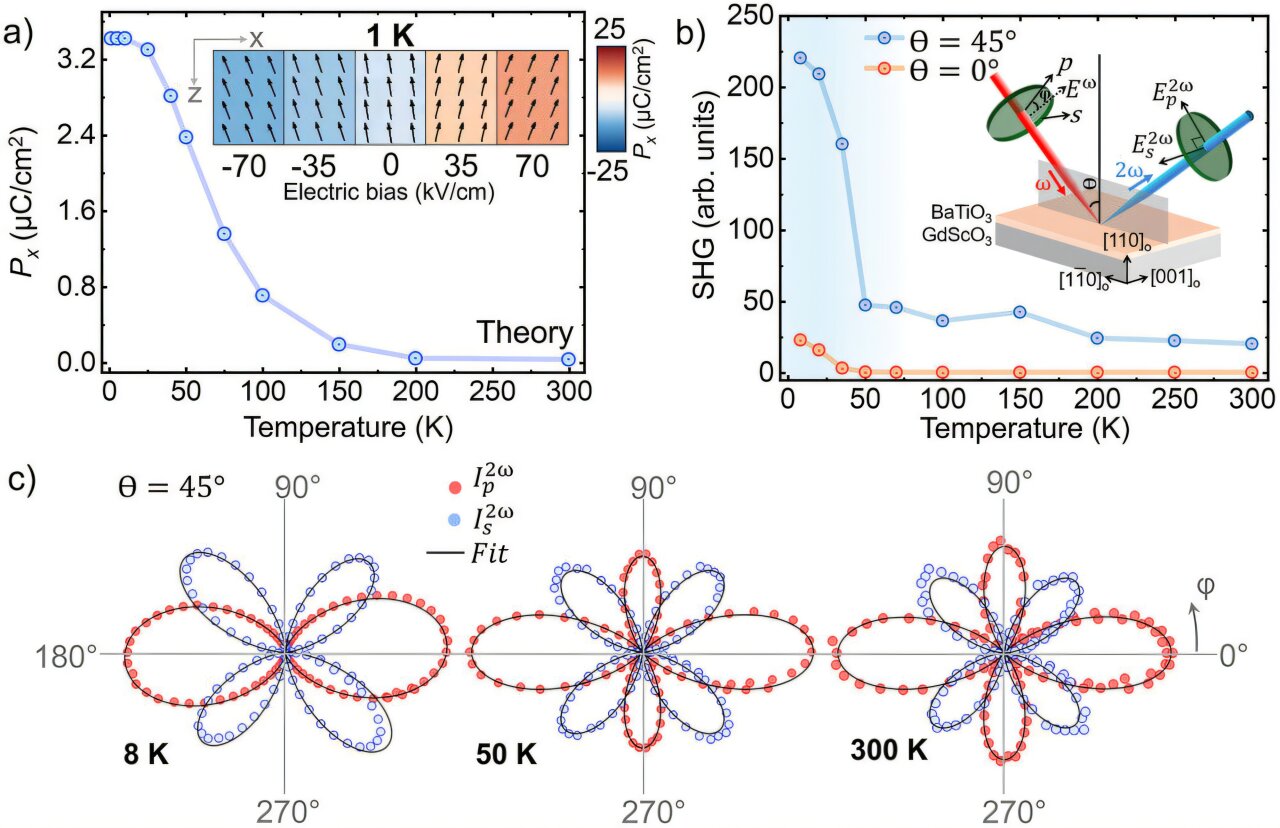

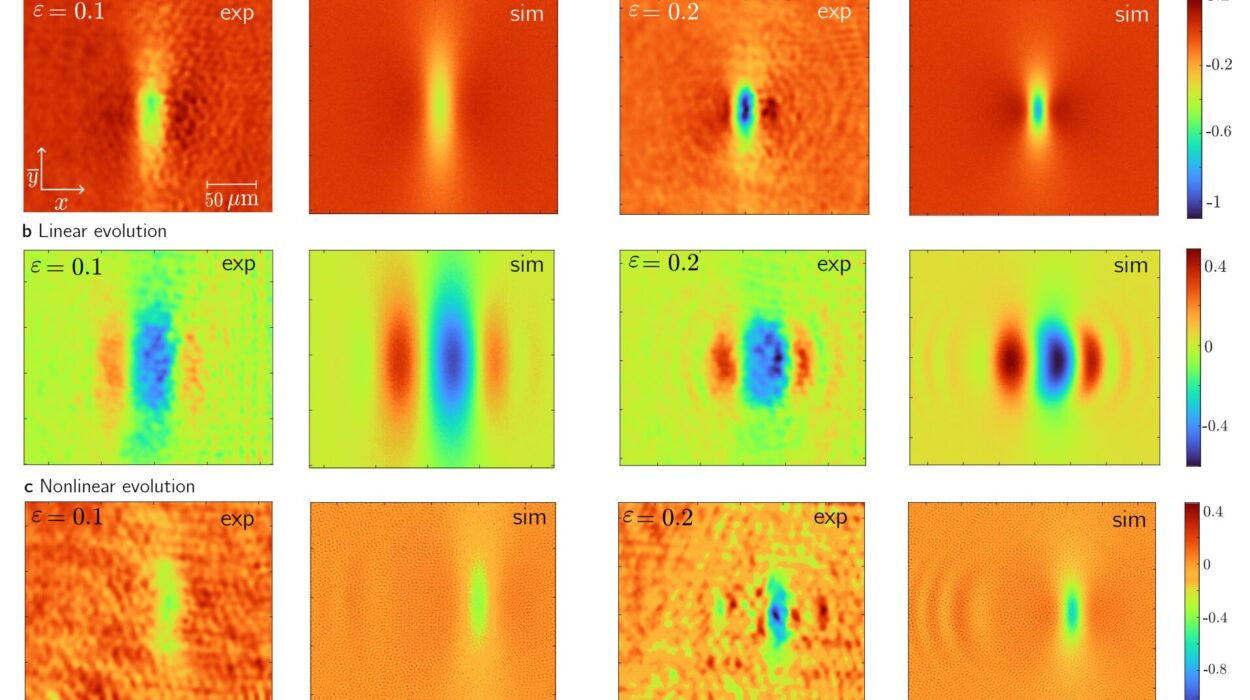

At the heart of the discovery is a concept both simple and profound: strain. When researchers grow a crystal on top of another with slightly different atomic spacing, they can “stretch” or “compress” the atoms in the upper layer. This controlled strain can change the material’s internal structure—and with it, its properties.

The Penn State team, led by materials science professor Venkat Gopalan, created barium titanate films just 40 nanometers thick—thousands of times thinner than a human hair. They then grew these films on another crystal substrate, forcing the atoms into new positions.

This manipulation created what scientists call a metastable phase—a structure that doesn’t occur naturally but can exist under the right conditions. And that’s where the magic happened.

“The metastable phase we created not only avoided the performance drop seen in the stable version, but it also showed a response that was exceptional,” said Gopalan. In other words, the team had unlocked a version of barium titanate that performed better than ever before.

A Leap for Quantum Technology

Quantum computing is one of the most ambitious scientific frontiers of our time. It promises machines that can perform calculations billions of times faster than classical computers, unlocking new possibilities in cryptography, medicine, climate modeling, and artificial intelligence.

But one of the biggest challenges in realizing this dream lies in communication—specifically, how to transmit information between quantum systems.

Current quantum computers use microwave signals to communicate between qubits, the quantum version of bits. These signals work fine over short distances, but they fade quickly. That means connecting quantum computers across cities—or even continents—is nearly impossible with today’s methods.

To build a true quantum internet, information needs to travel as light, not microwaves. And to make that possible, scientists must develop highly efficient devices that convert electrical signals from quantum circuits into light signals that can travel through optical fibers.

The new barium titanate films do just that—at more than ten times the efficiency previously seen at cryogenic (near-absolute-zero) temperatures. And they can do it at room temperature.

This breakthrough could open the door to quantum communication networks that use the same fiber-optic infrastructure already connecting our digital world today.

Powering a Cooler, Greener Internet

The implications don’t stop with quantum computing. The same technology could help solve one of the biggest challenges of the information age: energy consumption.

Modern data centers—the beating hearts of cloud computing, AI, and global communication—consume staggering amounts of energy. Much of that energy doesn’t even go into computing itself, but into cooling the systems that overheat from electrical resistance.

Photons, the particles of light, don’t generate the same heat as electrons when carrying information. Replacing traditional electrical interconnects with optical ones could dramatically reduce the power needed to run and cool data centers.

“Integrated photonic technologies are becoming increasingly attractive to companies that use large data centers to process massive data volumes, especially with the accelerating adoption of AI tools,” said Aiden Ross, co-lead author of the study.

By allowing information to be transmitted as light rather than electricity, these new barium titanate films could help build faster, cooler, and far more energy-efficient systems—reducing the environmental footprint of the internet itself.

The Metastable Miracle

One of the most intriguing aspects of the discovery lies in the idea of metastability.

Albert Suceava, a co-lead author and doctoral researcher, explains it through a simple analogy: imagine a ball resting on a hill. Naturally, it wants to roll down to the lowest point—the most stable position. But if you hold it gently in your hands halfway up the slope, it can stay there for as long as you keep it supported.

A metastable phase is like holding that ball—it’s not the natural resting point for the atoms, but with the right conditions, it can persist. And sometimes, in that delicate balance, materials reveal entirely new and extraordinary properties.

In the case of barium titanate, its metastable form proved to be a revelation. It retained its electro-optic performance at low temperatures—something the stable form could not do—and amplified its conversion efficiency in ways that stunned even the researchers themselves.

From the Lab to the World

While this discovery is still in the research phase, its implications are vast. The Penn State team believes their approach can extend far beyond barium titanate.

“Achieving this result with barium titanate was a case of taking a new material design approach to a very classic and well-studied system,” Gopalan said. “Now that we understand this strategy better, we have some less well-studied materials we want to apply it to. We’re optimistic some of them will exceed even the incredible performance we’ve seen here.”

This optimism is not unfounded. By exploring how atomic strain and metastability can redefine material behavior, scientists may be on the brink of a new era in electro-optics—one where classic materials, reshaped at the nanoscale, unlock the next wave of computing and communication technology.

The Human Side of Discovery

Science often moves quietly, built on patience, precision, and persistence. But moments like this—when a once-forgotten material finds new purpose—remind us that innovation is rarely about starting from scratch. Sometimes, it’s about looking again at what we already have, and seeing it in a new light.

The story of barium titanate is a story of second chances. It’s about how decades-old knowledge can be revived with modern tools and fresh imagination. And it’s about how curiosity, more than anything else, continues to push human understanding forward.

As the world races toward faster, greener, and smarter technologies, the humble crystal first discovered more than eighty years ago might just become one of the most important materials of the 21st century.

A Bright Future, One Photon at a Time

The journey from electrons to photons mirrors humanity’s own journey—from understanding to illumination. In learning how to better bridge the two, scientists are not only improving how we process and share information but also redefining the boundaries of what’s possible.

From quantum networks to energy-efficient data centers, the possibilities now glimmer brighter than ever. And somewhere, inside a lab at Penn State, a thin film of barium titanate—just a few atoms thick—is quietly showing us what the future of light and life might look like.

More information: Albert Suceava et al, Colossal Cryogenic Electro‐Optic Response Through Metastability in Strained BaTiO3 Thin Films, Advanced Materials (2025). DOI: 10.1002/adma.202507564